EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Great Recession and its aftermath have adversely impacted the operations of nonprofit organizations (Nonprofit Finance Fund 2011) at the very time that demand for services is increasing. This circumstance, and recognition that the current economic downturn may be of extended duration, has prompted renewed discussion of how nonprofit organizations might create economies of scale through innovative business combinations.

While the scale of individual nonprofit organizations may have little relevance to solving some social problems (John Kania Winter 2011), it is an important and timely consideration in the evolution of the fragmented behavioral health and social services industry. Changes in the industry’s operating environment are harbingers of rapid consolidation, especially within the fragmented nonprofit provider sector. These changes include differences in the way services are delivered and financed, shifts in legislation and regulation, consumer preferences and provider leadership. This new environment presents the typical undercapitalized nonprofit human service provider with the need to provide an expanded array of often technology-enabled services, under an unfamiliar, at-risk contractual arrangement, frequently during a period of executive transition. These challenges have been exacerbated by the economic downturn, which has given rise to an intense provider rivalry encouraged by payors seeking to reduce costs.

As in other industries, these circumstances encourage industry consolidation and hence, the evolution of a market for corporate control. Yet very few nonprofit organizations possess the capital, competencies or experience required to execute a consolidation strategy. Furthermore few are in a position to develop the required capabilities due to structural and other barriers associated with traditional nonprofit business models. These models have historically been program-centric and differentiated primarily as a consequence of their size, as measured by annual revenues.

Clearly, a new business model is needed for the new paradigm; one that enables nonprofit organizations to adapt to the Industry’s greater demands and the emerging market for corporate control, without sacrificing core values. The goals of the new business model will be rapid growth supported by improved governance and new mechanisms for accumulating capital. The measure of its success will be unprecedented compound annual growth rates of revenues and net assets resulting from business unit expansion across a broad geography and range of human services.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Great Recession and its aftermath have adversely impacted the operations of nonprofit organizations (Nonprofit Finance Fund 2011) at the very time that demand for services is increasing. This circumstance, and recognition that the current economic downturn may be of extended duration, has prompted renewed discussion of how nonprofit organizations might create economies of scale through innovative business combinations.

While the scale of individual nonprofit organizations may have little relevance to solving some social problems (John Kania Winter 2011), it is an important and timely consideration in the evolution of the fragmented behavioral health and social services industry. Changes in the industry’s operating environment are harbingers of rapid consolidation, especially within the fragmented nonprofit provider sector. These changes include differences in the way services are delivered and financed, shifts in legislation and regulation, consumer preferences and provider leadership. This new environment presents the typical undercapitalized nonprofit human service provider with the need to provide an expanded array of often technology-enabled services, under an unfamiliar, at-risk contractual arrangement, frequently during a period of executive transition. These challenges have been exacerbated by the economic downturn, which has given rise to an intense provider rivalry encouraged by payors seeking to reduce costs.

As in other industries, these circumstances encourage industry consolidation and hence, the evolution of a market for corporate control. Yet very few nonprofit organizations possess the capital, competencies or experience required to execute a consolidation strategy. Furthermore few are in a position to develop the required capabilities due to structural and other barriers associated with traditional nonprofit business models. These models have historically been program-centric and differentiated primarily as a consequence of their size, as measured by annual revenues.

Clearly, a new business model is needed for the new paradigm; one that enables nonprofit organizations to adapt to the Industry’s greater demands and the emerging market for corporate control, without sacrificing core values. The goals of the new business model will be rapid growth supported by improved governance and new mechanisms for accumulating capital. The measure of its success will be unprecedented compound annual growth rates of revenues and net assets resulting from business unit expansion across a broad geography and range of human services.

INDUSTRY BACKGROUND

INDUSTRY BACKGROUND

The behavioral health and social services industry (the “Industry”) is defined here to include the approximately 7,000 private nonprofit and for-profit companies that provide services in the following segments: behavioral health and substance abuse, developmental disabilities, juvenile justice, child welfare, and special and alternative education. These services are typically administered by agencies of state and local government on behalf of children or others with limited capacity to voice their own needs or desires.

Federal and state governments have played a central role in shaping competition in the Industry because they are both capable of licensing and regulating providers, and are among the largest buyers of services. With the growth of the welfare state in the 1960s, the delivery of Industry services shifted from government to largely private, nonprofit organizations. These nonprofit providers became increasingly reliant upon fees paid by public agencies for survival, while at the same time receiving fewer charitable contributions. Public policies have therefore been the key driver of an Industry historically characterized by low entry barriers, high exit barriers (specifically for nonprofits), few threats of substitute products or services (the noteworthy exception being pharmaceuticals), limited bargaining power of suppliers and little rivalry among existing competitors.

In 2004, after two generations of rapidly growing Industry revenues, the Industry began a transition to maturity as segments such as developmental disabilities experienced (between 2004-2006) the slowest increase in state spending on community and institutional services per $1,000 of statewide personal income in the previous 30 years (David Braddock 2011). The impact of Industry maturity in behavioral health and social services has been similar to that seen in other industries and has included: (a) more competition for share as revenue growth has slowed (b) greater purchasing sophistication by [largely governmental] buyers, (c) competition focusing on greater cost emphasis and (d) falling provider profits. Perhaps of greatest importance for the many small nonprofit providers in the highly fragmented Industry, rapid growth can no longer be relied upon to compensate for strategic errors, poor execution, or inadequate capital structures.

To date, the traditional response to Industry maturity – consolidation – has been thwarted due to the large number of nonprofit service providers. Despite clear evidence of economies of scale and scope, nonprofit providers lack the capital or management capabilities required to execute roll-up strategies, yet continue to face imposing barriers to exit.

As public funding mechanisms have shifted from cost-based and fee-for-service arrangements to managed care and more recently, to risk-sharing arrangements, the dominant position of nonprofit providers has been challenged by the emergence of publicly-traded and private, for-profit providers. These for-profit market participants may have much greater financial and human resources than their nonprofit counterparts, which enables them to share financial risk with payors. While I estimate that for-profit providers comprise only about 15% of Industry providers, consolidation efforts undertaken by the Industry’s for-profit providers have led to the creation of four firms (i.e., National Mentor, Res-Care, Providence Service Corporation and the Behavioral Health division of UHS) with revenues in excess of $1 billion. (The largest independent nonprofit human services providers have approximately $500 million in revenues). This growth of for-profit providers has been accomplished despite having been largely limited to transactions with other for-profit providers due to legal, regulatory, and judicial barriers facing for-profits acquiring nonprofits, including both overt and subtle public policies favoring nonprofit providers.

Still, there has been no response from the vastly larger nonprofit industry segment to this threat to nonprofit hegemony. Understanding why nonprofit providers have eschewed consolidation - and why that is about to change as the nonprofit business model evolves - requires knowledge of key differences between nonprofit and for-profit organizations and the ways in which these differences impact their business models and strategies.

A PRIMER ON NONPROFITS

A PRIMER ON NONPROFITS

Nonprofit organizations are a creation of state law, whereas tax exemption is primarily a function of federal tax law. Tax-exempt status confers two potentially significant benefits on nonprofit organizations: they pay no taxes with respect to net income on charitable activities, and donors may deduct contributions to most tax exempt-entities. To secure a nonprofit designation and tax exemption status, nonprofit organizations agree to serve one or more specified public purposes, and accept a prohibition on the distribution of profits which must instead be reinvested to further the organization’s charitable purpose. Nonprofit organizations have no owners, and are self-governing bodies.

The absence of an ownership interest has at least two significant effects on the operation of nonprofit organizations: it limits access to capital since there are no equity investors, and it dilutes governance by impairing ownership’s traditional role as a constraint on management’s pursuit of private interests. The limited access to capital further hinders the Industry’s nonprofit providers’ ability to invest in facilities, technology, management and working capital. It also handicaps the capacity to finance participation in Industry consolidation. As a result of these restrictions, nonprofit providers have grown almost exclusively through de novo development, and there are no national nonprofit consolidators. This evolution of the nonprofit sector has concurrently served the interests of nonprofit managements who have demonstrated a predictable reluctance to pursue the scale economies associated with business combinations, at the risk of their own personal positions.

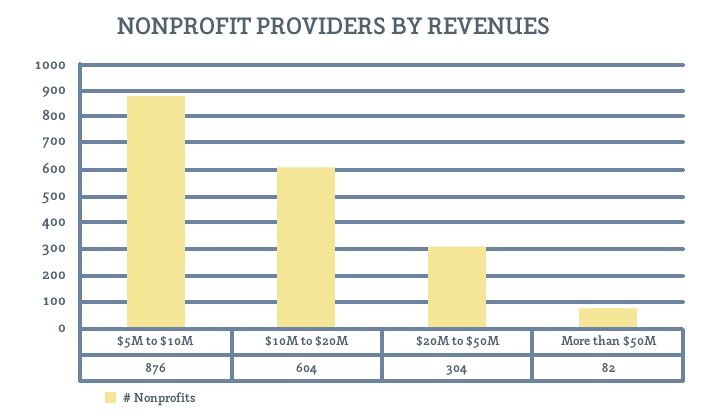

As a consequence, the nonprofit segment of the Industry remains fragmented. A search of the form 990 tax returns for 2009 in the Guidestar database reveals approximately 1,900 nonprofit human services providers with revenues of $5 million or more. The distribution of these nonprofits by annual revenues is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Nonprofit Providers by Revenues.

While these circumstances would seemingly pave the way for Industry consolidation led by for-profit providers, this outcome has been thwarted by multiple obstacles. Foremost among these issues is the widespread belief among nonprofit trustees that the profit motive is incompatible with the mission of providing behavioral health and social services, compounded by a preference of many public officials and payors for nonprofit providers. Absent financial distress, these factors have often precluded nonprofit providers from responding to business combination proposals from for-profit consolidators – and there have been no nonprofit consolidators. Thus, nonprofit governance confronts a situation in which it has been unable to achieve scale in an industry entering maturity, yet unable to exit due to a self-imposed absence of a market for corporate control. The resulting excess capacity in the maturing industry suppresses the margin expectations of would-be consolidators, whether nonprofit or for-profit. This outcome isn’t serving the public interest; however, this recognition has initiated a variety of public policy responses.

These public policy responses have included the introduction of new forms of incorporation by various state governments. A low-profit limited liability company, or “L3C,” is a legal form of business entity created to bridge the gap between non-profit and for-profit investing by providing a structure that facilitates investments in socially beneficial, for-profit ventures. To date L3C legislation has been adopted in nine states. Another alternative enacted in seven states is the “B Corporation,” which also combines elements of for-profit and nonprofit corporate forms. Other proposed innovations include social impact bonds and the C3SOP® (see the accompanying article describing C3SOPs in this issue). Each of these reactions is intended to address the capital access limitations inherent in the nonprofit corporation structure, ultimately enabling nonprofits to achieve critical mass while reducing unit service costs.

THE CHANGING INDUSTRY ENVIRONMENT

THE CHANGING INDUSTRY ENVIRONMENT

Changes in the Industry as a direct result of legislation, including the 2010Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“PPACA”)and the 2008 Mental Health Parity Act, have been widely publicized but are hardly the only shifts impacting the Industry. Hoping to gain lower costs and better value, the service delivery system is moving towards integrated behavioral health models that rely upon evidence-based treatments, augmented by technology and focused on outcomes. The traditional and expensive alternatives, particularly inpatient and other out-of-home treatment options billed by unit of service, are discouraged. Consequently, inpatient costs as a percentage of total behavioral health expenses have declined sharply, while substitute products like pharmaceuticals, telehealth and other technology-enabled forms of support, continue to play a growing role in the service delivery system.

Such shifts in service delivery will have a significant impact on Medicaid, a major payor for Industry services. Medicaid enrollment stood at 46.9 million on June 30, 2009 – approximately 15% of the population – and is expected to increase by 16 million participants following the implementation of PPACA (John Holahan 2011). Expected increases in states’ Medicaid costs range from $21.1 billion to $43.2 billion over the years 2014-2019 (Dorn 2010). These increases in Medicaid enrollment and costs occur at a time when state revenues remained 7 percent below pre-recession levels as of Q3 of 2011, and states’ fiscal challenges also include education and criminal justice systems. Collectively these circumstances compel public officials to pursue opportunities aimed at reducing state expenses, in part by changing the way they contract for services, and by privatizing some functions previously performed solely by government.

Shifts in financing arrangements prompted by new legislation and changes in service delivery have taken the form of risk-based contracting. These contractual arrangements require substantial capital capacity coupled with vastly improved accounting, information and management systems leaving most nonprofit organizations possessing modest equity at a distinct disadvantage. The capital shortfall cannot be simply addressed through the issuance of tax-exempt bonds, because tax-exempt financing is typically restricted to “bricks and mortar” investments. Thus, the shifts in financing encourage nonprofits to affiliate in order to create a more robust balance sheet.

Pervasive capital constraints have had a decidedly corrosive impact on Industry leadership. A 2006 study conducted by Compass Point and the Meyer Foundation queried 2,000 nonprofit executives and found that three-quarters of the executives do not plan on being in their present position in five years (Jeanne Bell 2006). More recently, Challenger and Gray reported that healthcare and nonprofit organizations had the highest CEO turnover during Q1 of 2012.

Collectively, market trends are compelling providers to evolve dramatically different care delivery systems, new management practices, and new strategies – in essence, an entirely new business model - in response to the paradigm shift.

PREVAILING NONPROFIT BUSINESS MODELS

PREVAILING NONPROFIT BUSINESS MODELS

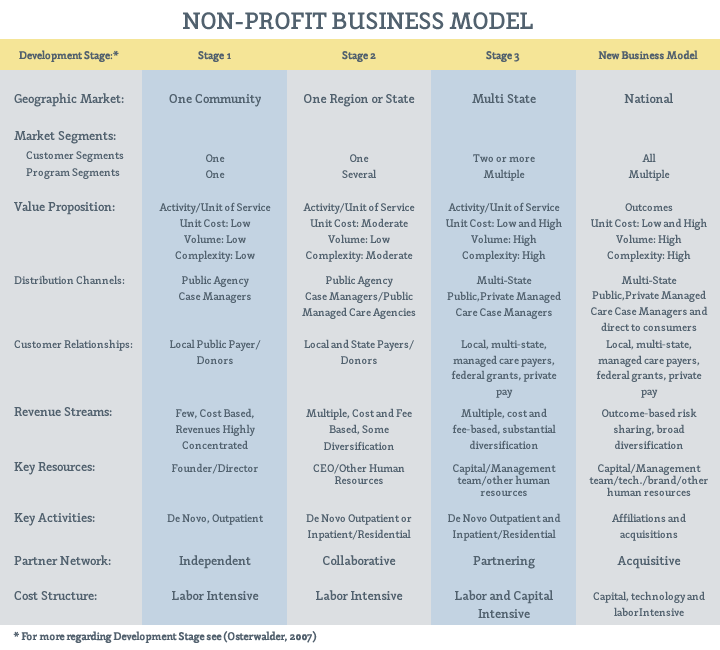

The industry’s nonprofit business models have historically been program-centric, and differentiated primarily as a consequence of their size, as measured by annual revenues. As a result, providers typically transition from one generic business model (Osterwalder 2007) to another in three phases as summarized in Table 1.

The Phase I business model is typical of nonprofit human services providers with revenues of less than $10 million. These providers characteristically offer a single service within a single community (e.g., an outpatient behavioral health service or residential service for developmentally disabled persons) that is funded by a single public payor, such as a county Department of Human Services. Individuals or families receiving service might be referred by a public agency case manager and likely do not present with multiple chronic conditions, and can likely be served at low cost. These providers most often will have limited histories and capital, and fees are often earned under low-risk, cost-based contracts. Many Phase I providers are led by their founders, who often possess additional product-related expertise.

Phase II providers include those with revenues of $10 million to $50 million. These providers have evolved to offer several services (e.g., behavioral health and substance abuse outpatient services, or residential and vocational services for developmentally disabled persons) regionally or statewide, and are funded by a several public payors. Individuals or families receiving service might be referred by public agency case managers or managed care organizations, and some of these clients have service needs of moderate complexity, entailing moderate expense. These providers may have histories of ten years or more but still lack significant capital due to revenues derived under a combination of cost-and fee-based contracts. Many providers transition to leadership by non-founders in the course of Phase II.

Phase III providers include the largest and best-capitalized providers. This structure offers a broad array of services for children, adults and families .in multiple states, and may be funded by numerous public and private payors. Individuals or families receiving service might be referred by public agency case managers and Medicaid and private-managed care organizations. These providers typically have long histories and have likely accumulated substantial capital, much of which is invested in real estate. Revenues are earned from many payors, and diversification of revenue streams has been a key driver of corporate strategy.

The typical Phase I organization structure consists of a single nonprofit tax-exempt enterprise that houses both service operations and fundraising, if the organization engages in any formal fundraising effort. Phase II organizations frequently incorporate a separate charitable foundation to administer fundraising efforts and to separately house the net capital accumulated by the development effort. Phase III providers usually adopt a holding company structure that includes multiple nonprofit providers, each a de novo venture established to address some unmet community need, and typically focused on a

specific program. The venture may even operate in several different states. In these Phase III organizational structures, the parent company frequently operates as a management company in an effort to benefit from scale economies.

This evolution of organizational structures has little impact on capital accumulation but significant impact on nonprofit governance. The decision to create a Foundation in Phase II adds significantly to the aggregate number of nonprofit enterprise trustees. Expanded board participation becomes unwieldy as Phase II operations become more complex, giving rise to trustee term limits during the Phase when organizational founders are succeeded by professional managers. Trustee term limits tend to exacerbate the information asymmetry between nonprofit trustees and nonprofit management, increasing agency costs. The commercial world’s antidote to agency costs – a market for corporate control – has not been operational in the Industry historically, but the changing Industry environment offers a catalyst. Payors increasingly demand integrated services that provide better outcomes at lower costs, and these demands are enforced through risk-sharing contracts that require larger, better-capitalized providers.

PREVAILING FOR-PROFIT BUSINESS MODEL

PREVAILING FOR-PROFIT BUSINESS MODEL

While the Industry’s for-profit consolidators include both publicly-traded and private corporations, each pursue roll-up strategies supported by a similar business model. Roll-up strategies seek to create value in fragmented industries by combining a multitude of smaller organizations into one larger company. A skilled, experienced management team can create scale economies, and the consolidated enterprise will receive significantly higher valuation multiples than those connected to the acquired entities individually. The key value drivers associated with this strategy are capital and exceptional management.

At the inception of a roll-up, investors – often private equity firms – capitalize a management team comprised of industry experts who proceed to acquire a strong platform company. (Industry platforms typically have about $40 million in revenue and EBITDA of $5 to $8 million). Following the initial platform acquisition, a series of regional add-on transactions are pursued while a search commences for platforms in other regions of the nation, in order to expand both geographic coverage and product lines, ultimately leading to a nationwide network. The relentless focus on growth via M&A typically leads roll-ups to enter multiple program and customer segments in an effort to maximize top line revenue growth and scale economies. Customer relationships include local and state agencies and managed care and insurers nationally. Revenue streams tend to be fee-based and broadly diversified. The evolution of ResCare, National Mentor, and Providence Service Corporation all followed this path.

Successful execution of a roll-up strategy promises substantial rewards stemming from the competitive advantages in the emerging marketplace associated with scale. Creation of a nationwide service network will enable large providers to enter into risk-sharing contracts that cover large numbers of beneficiaries over broad geographies at competitive prices. Concurrently, scale will facilitate accelerated rates of growth as the economic downturn compels smaller industry participants to exit. As the industry consolidates, the scale achieved by the consolidators will enable them to leverage the growing cost of technology and compliance over a large revenue base, and subsequently erect barriers to entry. The marketplace will reward these developments with growing multiples.

With the economic downturn and disarray in capital markets since 2008, Industry roll-ups have had to deal with a dearth of transactions in recent years. The pain experienced by the Industry’s leading for-profits has been mirrored by increasing financial distress at some of the Industry’s largest nonprofits. As the economy enters its fifth year of negligible economic growth, pressure grows on providers with weakening balance sheets to reassess strategic alternatives. With their structural, financial and managerial advantages, for-profit roll-ups seem the likely beneficiaries, but national nonprofit consolidators, invigorated by new business models and refined strategies, might still emerge.

NEW INDUSTRY NONPROFIT BUSINESS MODEL

NEW INDUSTRY NONPROFIT BUSINESS MODEL

Ventures that transform industries require more than innovative ideas, careful planning and a capable management team; a timely market introduction is also critical. The current recession has resulted in an extended interval of constrained capital access for small companies, low valuations multiples and modest deal flow. In anticipation of the Fed’s intent to maintain low interest rates for an extended interval, the likelihood of increases in capital gains and income tax rates, and growing pressure on government to curtail budget deficits, timing is ideal for Industry consolidation.

Capitalizing on the opportunities presented by the new human services paradigm will require nonprofit providers to adopt a new business model capable of pursuing traditional consolidation strategies supported by innovative organizational and financial design. The goals of the new business model will be two-fold: rapid growth supported by improved governance, and new mechanisms for accumulating capital. The measure of success will be unprecedented compound annual growth rates of revenues and net assets resulting from business unit expansion across a broad geography and range of human services.

Strategic Characteristics: The new nonprofit business model must support a strategy that recognizes mergers and acquisitions (or affiliations, as change of control transactions involving two or more nonprofits are termed) as an organizational skill that can serve as a key element of differentiation. Actions stemming from this awareness include:

• The adoption of management-designed and Board-approved formal acquisition criteria, encompassing a defined acquisition process with an emphasis on speed of execution

Speed of execution is critical because a successful nonprofit consolidator must overcome the presumption that nonprofits are incapable of executing transactions in an expedient manner. Expediency is also important because the present economic environment is at a peak for nonprofit consolidators due to the unprecedented level of interest rates, the large number of nonprofits facing leadership transitions, and pervasive concerns about a long-term decline in public funding for Industry services.

• Utilization of both experienced, in-house business development professional(s) and business brokers to maximize deal flow, as nonprofit transactions frequently entail an extended sales process

The extended sales cycle associated with nonprofits results from the absence of any ownership interests to drive transactions, cumbersome trustee processes and a lack of top management sophistication. As these roadblocks cannot be overcome through the actions of the nonprofit consolidator, it is necessary to generate robust deal flow via a business development organization able to create, pursue and monitor deal flow.

• Recruitment of legal counsel knowledgeable and experienced in both M&A and nonprofit law, along with outsourced due diligence support (at least for the initial transactions)

Legal counsel plays an important role in the execution of commercial transactions, and this role is critical in nonprofit transactions due to many unique aspects of nonprofit affiliations. The nonprofit consolidator’s counsel will routinely be placed in the position of drafting not only the affiliation agreements and the numerous resolutions to be adopted by the boards of the consolidator and the target nonprofit, but also educating the target’s general counsel on the nuances of the pertinent law. Transactions may also involve additional complexities associated with outstanding tax-exempt debt.

The acquirer’s due diligence programs seek to both minimize risk and create future value. These important dual objectives should be entrusted to experienced experts, and any attempt to maintain this capacity in-house risks delay of execution for consolidators pursuing multiple transactions simultaneously, but having only limited control over the pace of transactions. This circumstance invites outsourcing of due diligence, given the historically low volume of industry affiliations, and shortage of industry-experienced experts.

• A willingness and capacity to deploy capital to induce nonprofit targets with superior growth prospects to affiliate, specifically targeting nonprofit organizations facing transitions in the executive suite.

In that transactions with distressed providers – a mainstay of nonprofit affiliations historically – do not augment capital capacity by definition, these should not have a role in executing a consolidation strategy. To facilitate transactions with healthy nonprofits, cash transfers from the consolidator to the new affiliate on the closing date will become a fundamental ingredient of nonprofit affiliation strategy. These cash transfers are useful to nonprofit consolidators because they do not constitute a “price,” shorten the sales cycle, and enable consolidators to more rapidly increase net assets.

Organizational Characteristics: Implicit in its strategic focus on consolidation, the new nonprofit business model will incorporate a holding company organizational structure to facilitate changes in corporate control, capital formation, efficiency, transaction processing, and risk mitigation. Specifically, the holding company organization structure can be expected to yield the following benefits:

• Entry into New Geographic and Program Markets Quickly and at Scale: The nonprofit holding company structure enables a nonprofit consolidator to add multiple affiliates easily via a change in the affiliate’s Articles of Incorporation. These Articles are typically amended on the closing date to provide that the parent company (or an existing affiliate of the parent company) will become the sole member of the new affiliate, with the power to appoint and remove affiliate trustees, among other things.

• Avoid Relicensing and Contract Assignments: Growth by affiliation or acquisition – i.e., deals analogous to stock transactions rather than asset purchases - enables the parent company to avoid relicensing of existing services and assignment of the affiliate’s various contracts and receivables.

• Acquisitions, In Addition to Affiliations: The nonprofit holding company structure facilitates a nonprofit consolidator’s acquisition of for-profit, as well as nonprofit providers. In many circumstances the acquired entities will continue to operate on a for-profit basis, blurring the distinction between nonprofit and for-profit providers.

• Centralized Governance: The sole member organizing principle allows for centralized control and decision making at the parent company level, including centralized decision making with respect to capital allocation. These are essential tools for executing strategies involving goals related to care integration, technology investment, obtaining scale economies and management accountability.

• Enhanced Management Performance: Execution of a successful growth strategy focused on acquisitions requires the engagement of senior executives with skills and experience that vary from traditional nonprofit leaders, incentivized by contractual arrangements that better align organizational and management interests.

Financial and Operating Characteristics: Implicit in its strategic focus on consolidation, the new nonprofit business model will incorporate an intense focus on capital accumulation and scalable information systems because these are fundamental requirements to execute consolidation strategies. Financial and operating policy implications of the new nonprofit business model include the following:

• Balance Sheet Focus: The financial management of Industry nonprofits has historically focused on the Income Statement, with boards typically adopting annual budgets for revenues and expenses with scant attention (if any at all) to pro forma balance sheets. In the new nonprofit model, financial goals are measured by reference to changes in net assets because capital capacity is a function of net assets, and optimum size is driven by capital capacity.

• Defining and Targeting Optimum Organizational Size: The optimum size of a nonprofit organization is the maximum level of revenues that can be prudently sustained given the capital available to the nonprofit and expectations of future market conditions. The purpose of nonprofit budgeting is to quantify operating and business development activities intended to achieve optimum size over time.

• Value Creation Through Affiliations: Nonprofit business combinations can be expected to create increases in net assets each year equivalent to multiples of annual operating profits during the Industry’s consolidation phase, with first movers likely reaping the greatest benefit. Nonprofit affiliations differ from commercial acquisitions as there is typically no purchase price, though there will frequently be a cash transfer from the parent to the new affiliate at closing. (There is no accounting impact at the enterprise level stemming from these cash transfers as the consolidated financial statements of the parent include the cash of all affiliates. In short, cash transfers, in contrast to the purchase price in a commercial transaction, amount to merely moving cash from one pocket to another). Importantly, the assets, liabilities and net assets of new affiliates are consolidated on the financial statements of the parent company effective on the closing date at their fair market values – and so virtually every affiliation increases the net assets of the parent at closing. Essentially, the first affiliation begins a positive cycle in which every deal creates value for the parent, and this incremental value can enable each subsequent transaction as long as there is sufficient cash available to pay any required cash transfers.

• New Focus For The CEO: With business combinations having by far the greatest impact on growing net assets, nonprofit CEO’s must make planning, business development and board relations top priorities, leaving operations and fund raising to other executives. In so doing, the nonprofit CEO will be essentially mirroring his for-profit counterparts.

IMPLICATIONS AND SPECULATIONS

The adoption of the new nonprofit business model will have significant implications for the Industry. Most obvious will be increased efficiency resulting from better allocation of the capital available to the Industry. Less obvious but equally significant, the new business model will improve governance, management and systems leading to increased competitiveness, and ideally, effectiveness.

As a small cadre of regional and national providers generate a growing proportion of Industry revenues, it seems likely that distinctions between service providers related to their tax status will diminish. With the evolution of regional and national brands, it seems probable that the best capitalized and best known nonprofits – often faith-based organizations – will be the last nonprofits standing. I expect they prove a formidable foe to even the largest Industry competitors once greater industry concentration creates increased regulation, and cements lobbying as a distinctive competence in the Industry.

Bibliography

Bibliography

Bell, Jeanne, Richard Moyers, and Timothy Wolfred. Daring to Lead 2006: A National Study of Nonprofit Executive Leadership. San Jose, CA: CompassPoint, 2006.

Braddock, David, Richard Hemp, and Mary C. Rizzolo. The State of the States in Developmental Disabilities 2011. THE ARC NATIONAL CONVENTION EDITION: Department of Psychiatry and Coleman Institute for Cognitive Disabilities. Colorado: University of Colorado, 2011.

Holahan, John and Stan Dorn. What Is the Impact of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) on the States? Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, 2010.

Holahan, John, Lisa Clemans-Cope, Emily Lawton, and David Rousseau. Medicaid Spending Growth over the Last Decade. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Washington, D.C.: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2011.

Osterwalder, Alexander. How to Describe and Improve your Business Model to Compete Better. Melbourne: La Trobe University, 2007.

Author Bio

J. Kevin Fee is the founder and President of Angler West Consultants, Inc., a financial advisory firm focused exclusively on mergers and acquisitions of human services organizations. Founded in 1996, Angler West has been involved in more transactions involving human services organizations than any other intermediary over the past decade. Prior to Angler West, Mr. Fee had more than twenty-five years of experience serving as a senior executive of various nonprofit health and human services organizations. This experience included positions with providers of behavioral healthcare, substance abuse treatment and developmental disabilities programs. Mr. Fee has published articles on topics including financial restructuring, valuation, and governance of nonprofit organizations and presented at conferences on these and other topics.