The following was originally published by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government as part of its Occasional Papers Series.

I. Introduction

Twenty-five years of Innovations in American Government Awards at the Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government provide a testament to the creativity of public servants tackling challenging issues in health care, social services and community and economic development. Without question, government officials can be innovators themselves. But they can also help unleash innovation in their cities and communities by connecting local entrepreneurs, enacting favorable policy changes and mobilizing citizens behind reform. In the first paper of this miniseries, the authors introduced intentional strategies to promote local innovation, highlighting efforts in Boston, Denver and New York City. The authors then briefly presented their framework for understanding what is required to nurture a fertile landscape for innovation in local public problem solving. To begin a more structured exploration, this paper discusses the roots, composition and supporting evidence of the framework.

In The Power of Social Innovation: How Civic Entrepreneurs Ignite Community Networks for Good (2010), Stephen Goldsmith painted a picture of what an innovative city might look like and how its leaders might encourage more innovation in community problem solving:

This city would challenge assumptions, produce venture funding for new efforts, measure and enforce performance, and change the regulatory environment. A community determined to produce transformative social value would look to innovations that improve outcomes, regardless of whether the interventions involve reforming existing organizations, importing new ones, or devising hybrids. The community would make it easier for old and new players to expand and be creative by ensuring that rules, certifications, and other requirements operate to protect health and safety and not as barriers to entry that protect incumbent providers. In other words, the community would knit together the various threads explored in this book to create the best possible conditions for progress. It would aspire to intentionally position itself as a fertile place for civic progress (Goldsmith, Georges, & Burke, 2010, p. 220).

Critical to this vision of building an innovative jurisdiction, however, is looking beyond city government and towards cross-sector delivery systems. Goldsmith was not the first to suggest a system-level view of innovation in public problem solving. In 2004, Harvard scholars Sarah Alvord, David Brown and Christine Letts discussed how successful innovators in a community recognize the need to “expand and sustain their impacts and transform larger systems in which they are embedded” (2004). In 2008, Greg Dees and Paul Bloom, who lead Duke University’s Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship, described a variety of “players,” including funders, service providers, beneficiaries and constituents, as well as potential opponents (or those benefitting from the status quo) who might resist a particular innovation. “Environmental conditions” within the local “ecosystem,” Dees and Bloom added, include politics, bureaucratic structures, the regulatory environment, economics and markets, geography and infrastructure and culture and social fabric (2008).

All three of these system-level perspectives demonstrate how even the best policy and programmatic innovations are unlikely to take hold unless local governments better understand how to incorporate new models into a given community. In so doing, public officials can begin to chip away at the entrenchment that pervades so many systems. These perspectives also look beyond developing and incubating new ideas and address the more ambitious—and more difficult—challenge of taking an innovation from the margins into the mainstream. In pursuing this challenge, innovators must overcome the political, bureaucratic, legal and financial hurdles to testing or incorporating new approaches. The tendency to continue to fund status quo providers or models—regardless of results—rather than redirect dollars to alternative models with the potential for greater success is a powerful hurdle for any player in the local ecosystem to overcome. Given this reality, the authors have approached this miniseries of papers exploring local innovation in public problem solving with a focus on overcoming the major challenges facing the adaptation and diffusion of promising innovations across local delivery systems.

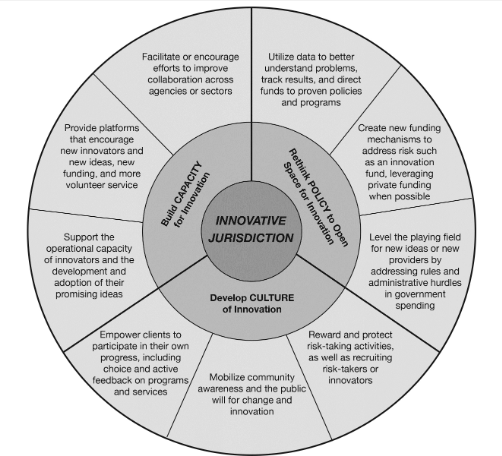

The Power of Social Innovation posits that mayors and other public officials can encourage more innovation in public problem solving through a series of changes to the local environment or ecosystem. Through their work to date, the authors of this paper have further developed this hypothesis to outline a set of proposed strategies for changing the local landscape for innovation. The first paper in this miniseries briefly introduced a framework for an innovative jurisdiction that includes: 1) build collective capacity to develop and execute on innovative solutions; 2) rethink policy to create the space for the best innovations to take hold and grow; and 3) encourage a culture of innovation both across delivery systems and among the general public. In this paper, the authors provide background on their research approach and then lay out the logic, relevant research and real-world examples supporting each strategy and component of the framework.

II. Research Method

In 2008, two public management scholars asked, “How can it be that public innovation takes place even though the culture of public administration makes it unlikely?”(van Duivenboden & Thaens, 2008). In crafting this framework, which is a culmination of five years of study and practice in the field of local innovation, the authors took this question quite literally. From 2008 to 2010, the Ash Center’s Innovations in Government Program convened an “Executive Session on Transforming Cities through Civic Entrepreneurship.” With support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the executive session brought together leading social entrepreneurs, big-city mayors and officials and leading experts for three years of in-depth deliberation. Led by Harvard professors Stephen Goldsmith, Mark Moore and Frank Hartmann, the group examined what it would take to change the environment in which communities solve public problems. Out of these discussions came a series of working papers, columns and Goldsmith’s book The Power of Social Innovation. A full list of participants and publications is available online at http://www.ash.harvard.edu/ash/Home/Programs/Innovations-in-Government/Social-Innovation/ Ideas. The book is also based on Goldsmith’s decades of experience and conversations with top innovators from a wide variety of sectors. Moore, the author of a seminal public management text, Creating Public Value (1995), continues to guide these efforts as well, most recently by encouraging the authors to identify the characteristics of an “innovative jurisdiction.”

In pursing this project, the authors interviewed, researched, consulted and, at times, collaborated with more than 100 innovators in the public, nonprofit and private sectors. The focus has been on not only the nature of the work of individual innovators but also the landscape of the cross-sector systems in which they operate. The authors are grateful to the many practitioners from across the country who were willing to speak candidly and in detail about their experiences. The authors also mined secondary research in an effort to capture a range of new initiatives by leaders in the field. A more detailed description of sources follows:

First-Person Accounts from Innovators: For the past few years, the authors have chronicled the firsthand experiences of many of the most successful innovators on the frontlines of public problem solving. Corresponding with the release of The Power of Social Innovation, the Project on Social Innovation—led by Gigi Georges and Tim Glynn Burke at Harvard Kennedy School’s (HKS) Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation—launched a campaign to share lessons from the innovators highlighted in the book. The project’s team invited leaders in the field to contribute experiential accounts to the HKS “Social Innovators Blog” and to “Better, Faster, Cheaper,” a blog on Governing.com, and to participate in a series of webinars hosted by HKS. The authors draw on these accounts for many of the examples below.

Innovation Strategies Initiative: With support from Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Project on Social Innovation’s team launched an initiative to help government officials navigate the strategic levers and promising practices that can help civic-minded innovators transform their approaches to public problem solving. The team worked with three cities—Denver, Nashville and San Diego—to help the cities implement some of the ideas in The Power of Social Innovation. For each city, led by a mayor known for his commitment to innovative problem solving, the team provided tailored research, consultation and on-the-ground support. Each mayor’s office, in turn, brought together local cross-sector interests with the objective of expanding the understanding, adaptation and dispersion of promising and locally relevant approaches. The team began its efforts by developing a self-assessment tool to uncover barriers and opportunities related to the local landscape for innovation. Taken together, the responses to all three surveys comprise valuable insights into urban innovation from almost 150 innovative problem solvers from across the country.

Entrepreneurship Hub/Incubator Survey: In early 2012, the authors conducted a multi-jurisdictional survey of local business incubators, social innovator hubs, economic development and competitiveness initiatives, entrepreneur ecosystem development efforts and cross-sector initiatives. Although the majority of respondents were from nonprofit organizations, their input is relevant and valuable to this work. Many have been refining their models for years and have unique insights into the needs of local innovators and entrepreneurs.

City Interviews: In the summer of 2012, the authors conducted in-depth interviews with chiefs of staff, chief innovation officers and other staff from ten U.S. cities whose mayors had noted innovation in public services as a priority. It became apparent through these discussions that the greatest challenge to innovation in many cities is not a lack of creativity or resolve. Rather, for many cities, it is the ability to overcome fiscal, political, regulatory, bureaucratic and cultural hurdles in the adoption stage (also see Borins, 1998). In addition to the three cases highlighted in the first paper—Boston, Denver and New York City—all interview subjects generously shared insights that continue to be critical to refining the framework.

III. Framework for an Innovative Jurisdiction

Below, the authors discuss the core strategies for improving the local landscape for innovation— a framework that they developed and refined using information gathered from the sources above. The authors then describe the framework logic, provide real-world examples for each component and offer concrete steps for putting each strategy into practice. The authors believe that this framework may help cities to enjoy a more robust pipeline of higher-quality innovations that will, in turn, lead to better solutions to challenges, increased cost savings, improved social outcomes and greater quality of life for residents.

Strategy 1: Building the Capacity of Local Innovators

The first strategy focuses on building the collective capacity of local innovators across the city, with capacity defined as “the facility or power to produce, perform, or deploy.” The innovative ideas required for a city to solve its most difficult and ongoing problems might come from any individual or organization within what Dees and Bloom call the local ecosystem (2008). However, for a transformation to occur, that idea must move from its origins on the margins (as a pilot program, for example) into the broader ecosystem. Thus, a local government that is actively seeking to become an innovative jurisdiction should not only identify and promote individual projects but also work to build the skills and organizational capacity of local innovators to develop, incubate, test, refine and scale their ideas. Building on Dees and Bloom’s ecosystem concept, the authors suggest that cities can improve the alignment and coordination of current efforts (ideally creating conditions under which the whole is greater than the sum of its parts); provide new entry points for players to get involved and help improve the effectiveness of existing players; and promote the adoption of the most promising innovations. The authors discuss in detail below each of three suggested components through which cities can develop the talents and capacity of local innovators and their organizations.

Improve Collaboration

The first component of building local capacity suggests that cities should initiate, facilitate or bolster efforts to improve collaboration across city agencies and sectors. There is significant literature documenting the benefits of cross-sector or cross-agency collaboration. For example, Stephen Goldsmith’s Governing by Network (2004) and Paul Vandeventer and Myrna Mandell’s Networks that Work (2007) discuss deliberate public-nonprofit-philanthropic cooperation. John Kania and Mark Kramer introduced the concept of “collective impact,” arguing that transformational change requires community leaders across an issue area (education, for example) to “abandon their individual agendas” and come together around “a collective approach” with common goals and common measures of success (Kania & Kramer, 2011). Pennsylvania’s Fresh Food Financing Initiative demonstrates how collaboration can lead to the effective design and implementation of innovative solutions. Harvard University’s Innovations in American Government Awards recognized this cross-sector effort in 2008 for bringing together “policymakers, business owners and bankers” as well as “extensions agents, health department officials and hunger advocates” to encourage supermarket development in underserved neighborhoods. Central to the initiative was Pennsylvania state legislator Dwight Evans, who describes the Fresh Food Financing Initiative as “a network, growing around a common purpose. The lesson is in how innovators can engage with relevant stakeholders and resources in new ways to create a good greater than any individual actor could create on its own” (Evans & Weidman, 2011).

The Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics in Boston and the Denver Office of Strategic Partnerships, as highlighted in the first paper, focus on the cities’ relationships with the local nonprofit sector, universities and foundations. The survey research uncovered a number of other efforts to promote collaboration. The Kentucky Philanthropy Initiative promotes strategic grant making and works to improve collaboration among early childhood programs. York University’s Knowledge Mobilization Unit in Toronto builds “relationships between researchers, community, industry and government.” The Texas OneStar Foundation seeks to “connect relevant stakeholders (government, nonprofit, business, foundation)” in its mission to strengthen the state’s nonprofit sector. Among formal efforts to promote collaboration within local government in particular, the Fairfax County (Virginia) Office of Public Private Partnerships works to “foster collaboration among nonprofit organizations and county agencies with common goals to improve efficiency and ability to leverage resources.”

Efforts to facilitate collaboration not only develop operational capacity but also help build pipelines for innovation by bringing together diverse talents and perspectives within a given community. Innovative ideas can sprout up at the intersection of different fields or disciplines. For example, in New York City, the iZone’s communities of practice and innovation clusters allow participating schools to “identify the emerging best practices in schools, and structure opportunities for these practices to be seen, adopted and adapted by others” (Gillett, 2012). In the work with local governments in Denver, Nashville and San Diego, a primary goal was to identify and connect promising local innovators within a given issue area. Led by core teams in each mayor’s office, participating innovators were encouraged to leverage their professional networks to build support for the project and lay the groundwork for each city to further integrate innovation and reform into its policies.

In Practice: Improve Collaboration

- Lay the groundwork for more effective partnering and collaboration through convening and training

- Facilitate new collaborative networks around a common purpose, with common measures of success

- Utilize cross-sector and cross-agency networks to identify and share best practices

Create Mechanisms to Attract New Innovators (and New Ideas)

A city can also work to build its shared capacity for innovation by creating more opportunities for citizens to contribute solutions. In The Power of Social Innovation, Goldsmith writes: “Government cannot and should not be the dominant source of assistance in a community. It does not possess enough funding, legitimacy within affected populations, or compassion to produce transformative change. Instead, social progress often depends on ‘little platoons’ of community volunteers or civic entrepreneurs who can catalyze, harness, and direct the enormous (and growing) reservoir of American goodwill” (Goldsmith et al., 2010).

Government can stimulate these ”platoons” and other types of private efforts by creating or supporting mechanisms that: solicit new ideas and solutions from citizens, provide opportunities for aspiring innovators to launch a new idea, encourage individuals and private entities with financial resources to donate to or fund effective solutions and open doors for others to get involved as volunteers. These mechanisms can take a number of forms. For example, Change by Us NYC is a do-it-yourself platform that promotes community engagement and social capital by leveraging social networks and digital technology, using the virtual world to organize grassroots change in the real world (Goldsmith, August 17, 2011). Describing the project that he helped launch as deputy mayor of New York City, Goldsmith explains how this platform allows “members to post ideas, join or create project teams, and easily access the resources of city agencies and community-based organizations...[Change by Us NYC] recognizes the unique power of social networking to link resources and ideas from multiple sources and mix them together to foster collaborative solutions more valuable than the sum of their parts” (Goldsmith, August 17, 2011). Although technology can be a powerful tool for attracting new people and new ideas, many cities do not have the financial resources or talent for adopting cutting-edge civic technologies. Others do not necessarily see the potential of these mechanisms to further innovation in their communities. In the surveys of Nashville, Denver and San Diego, only 27% of government respondents rated digital media (such as mobile or online technology platforms) as somewhat important or important tools for community engagement in their cities.

Innovation may also be captured through offline and more traditional recruiting mechanisms that enable citizens to launch new ideas or engage in their communities. A number of the innovation offices with whom the authors spoke are becoming hubs that actively seek out and attract creative ideas from city employees and the community (see related sidebar). Meanwhile, a number of national nonprofits like Teach for America, City Year, Fuse Corps and Code for America are also demonstrating how to spur innovation in communities through effective human capital pipelines for talented people from unconventional backgrounds. Civic Ventures, for example, is a national nonprofit that seeks to harness the energy of America’s 70+ million retiring baby boomers by matching them with meaningful volunteer and professional opportunities in their communities. It celebrates boomer-age innovators with its annual Purpose Prize and works with government and nonprofit organizations to take advantage of retiring boomers—what they call a “windfall of human and social capital” (Goldsmith et al., 2010). Executive Vice President Jim Emerman explains, “We hope that these and other pathways will enable more people to move into encore careers that combine personal meaning and social impact with continued income in the second half of life” (Balfanz & Emerman, 2011). By making people, rather than technology, the central platform for driving solutions, organizations like Civic Ventures can be an attractive model for some cities to pursue.

In some cities, the authors found that these innovation-specific efforts make a distinction between the innovator, whether an individual or organization, and the innovation or idea. But the two are inherently linked, particularly in the earliest stages. Effective mechanisms can encourage, in other words, both new innovators and new ideas. Similarly, as discussed in the next section, local governments and local intermediaries not only help build the operational capacity of innovators but also help develop and grow their ideas.

In Practice: Create Platforms for New Innovators

- Identify and encourage aspiring innovators within and outside government to pursue an idea

- Invest in civic technologies, or support local entrepreneurs, that crowdsource new solutions to public problems

- Encourage volunteerism and private funding and apply them where they will have the greatest impact

Ten Things Local Government Can Do to Build a “Safe Space” for Innovators and Their IdeasA number of cities expressed their belief in the value of creating a central innovation hub within City Hall or city government where anyone can come with a novel solution. The Boston Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics calls itself “the office of yes” and “the willing face of failure.” Nick Kittle, Manager of Innovation and Sustainability in Colorado Springs, tries to create a “safe space” for employees to talk with him about their ideas. Below is a list of ten tactics to help create a place within local government where innovating and taking risks is considered safe:

|

Develop Promising Innovators (and Their Ideas)

While innovators often have an intimate understanding of their communities, a deep well of goodwill and a great idea, they often lack other critical assets and skills—such as project management, team development and business planning. Importantly, they may have little knowledge or experience in navigating local politics or partnering with government bureaucracies. Another critical skill is rapid prototyping, or as the iZone’s Stacey Gillett describes, designing innovations in a way that allows policy makers or practitioners to quickly and accurately judge an idea’s potential before investing much money or time. Thus, a second component to helping build the shared capacity of local innovators is to provide the necessary resources to help mature the best ideas so that they can be developed, refined and eventually adapted, incorporated or diffused to new sites, agencies or even jurisdictions. Common approaches include financial support, technical or operational assistance, convening like-minded innovators and matching new innovators to mentors or investors.

The Denver Office of Strategic Partnerships, for example, offers training to help local providers compete for existing contracts or otherwise partner with the city. The Boston Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics provides modest seed money. Perhaps more importantly, it helps innovators navigate the local political environment and manage a messaging strategy. The iZone matches schools with external partners, provides professional and leadership development and invests in new technology at schools. It also brings innovative school leaders together into networks or clusters, where lesson sharing but also social pressure help advance each school’s efforts. Creating a community of like-minded innovators in this way can be a valuable support. In their research, Mark Casson and Marina Della Giusta find that “entrepreneurship is, in fact, socially embedded in network structures” (2007).

Skill and asset building are also conducted by local nonprofits and intermediaries that would welcome city government assistance and involvement. In Boston, the GreenLight Fund is a nonprofit intermediary that imports “innovative, high-performing nonprofits” into the city, after an analysis of the local ecosystem identifies gaps in existing services. In addition to its work identifying new models, the GreenLight Fund has become a national model for helping innovators to develop and grow their ideas. It recently opened offices in Philadelphia and San Francisco and won an award from the federal government’s Social Innovation Fund to support its expansion efforts. A model the GreenLight Fund recently chose to bring to Boston is Single Stop, a national nonprofit that connects low-income families to public benefits and services. In addition to start-up capital, GreenLight helps launch organizations like Single Stop by assisting with staff recruitment, board development, public relations and networking with funders and others in the field. In some ways, it is intuitive that new ideas need support to take hold and grow. Yet there is significant opportunity for local governments to do more to support and develop the most promising innovations and innovators, either directly or perhaps by supporting these local hubs and incubators.

In Practice: Develop Promising Innovators

- Provide resources, from skills training to messaging support, to local innovators; or support local hubs and incubators that help innovators outside government

- Install systems and supports to develop, test and refine the most promising innovations

- Provide mentoring and networking opportunities for aspiring innovators to connect with like-minded colleagues

Strategy 2: Rethinking Policy to Open Space or Innovation

In most cities and communities, municipal governments are the dominant funders of programs that address public problems and deliver basic services. Moreover, local government can dominate the workings of nearly every form of service provision that it touches—by regulating providers, setting credentials and deciding which organizations are qualified to provide services. Although they are often constructed for the purpose of stewardship and accountability, many of these policies tend to restrict more innovative funding and activity with public dollars. Andrew Wolk, founder of Root Cause, suggests that government can better support social entrepreneurship by creating an “enabling environment” that removes barriers and extends trust to new providers through policy changes related to exemptions, certifications and restrictions (Root Cause, 2007). Economist Maria Minniti has likewise explored the impact of government institutions and policies intended to promote entrepreneurship and agrees that “government should endeavor to create enabling environments” by focusing on the local policy landscape (2008, p. 787).

The second strategy in the framework echoes Wolk and Minniti, suggesting that cities should focus on reforming existing policies that restrict how public tax dollars are allocated towards solving problems. The authors offer three central components in this strategy to rethink policy- and decision-making processes, structures and values: more effective utilization of data, availability of risk capital and removal of barriers to increase competition.

Utilize Data

In The Power of Social Innovation, Goldsmith observed that it is often “political success, not consumer success, that drives social service delivery systems”(Goldsmith et al., 2010, p. 138). In these systems, risk-averse third parties determine which programs or services are available to citizens—and they are often those services delivered by providers with political savvy and connectedness. Yet the adoption and diffusion of innovation require that funders shift their financial resources away from ineffective, inefficient or perhaps misguided incumbent approaches (Goldsmith et al., 2010, p. 102). In an environment ripe for innovation and progress, outcomes and successful performance, not political considerations, should drive service delivery decisions. By building performance data and accountability into their decision making, government agencies can create a more effective marketplace for services. Governments are also improving upon the utilization of data by mining the vast amount of organizational data that they currently collect and store. Tapping into performance metrics and digital data warehouses in order to “discover and address civic problems before they occur” is the focus of the new Data-Smart City Solutions initiative of the Innovations in Government Program at the HKS Ash Center. Some examples of innovations in data capture and use include smart meters that offer useful information to customers and utilities alike, using offender and crime characteristics to tackle recidivism and predicting flooding patterns to better organize emergency plans. Learn more about these examples and the Data-Smart City Solutions initiative at http://datasmart.ash.harvard.edu/. The potential sources of data—and opportunities to utilize them—are vast, and local governments are creatively exploring these opportunities. For example, the Boston Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics is helping its Department of Public Works to collect data from citizens that make the maintenance of roads and streetlights timelier. Also, the ubiquity of online social networks and search engines allows cities to monitor public sentiment and identify issues earlier. In addition to mining their own data sources, local governments might also look to service providers with smart data and performance measurement systems as helpful partners in their efforts to focus on performance. In another example from Boston, Mayor Menino’s former Chief of Staff Judith Kurland writes of bringing the Family Independence Initiative (FII), a bold new approach to fighting poverty, to Boston: “FII’s data and policy innovations will be useful tools as we look to effect change across the whole system of funders and providers” (Kurland, 2010).

Prioritizing the capture and use of data to evaluate performance, focus on outcomes and fund results can present a host of implementation challenges for any local government including: enforcing accountability through performance-based contracts; consistent review of the alignment of goals, strategies and metrics; and resistance to a culture of compliance (Goldsmith et al., 2010, p. 127). The key is not just to collect data but to use the data collected, whether they are for performance or otherwise, to influence the future management of operations. HKS professor Robert Behn has studied CitiStat, CompStat and other performance management systems for many years. He recommends a list of critical implementation factors, only one of which is actually about measurement—the rest are about what an organization does with the data (Behn, 2012). Finally, it is important to note that increasing the capture and use of data to affect funding and policy changes also means increased accountability for local government itself. As Kurland writes, “It is important if we hope to change existing policies that we are equally willing to measure and be evaluated by the results. We must be committed to gathering, sharing, and comparing data” (Kurland, 2010). Performance data and measurement are the main subjects of the third paper in this miniseries.

In Practice: Utilize Data

- Collect data on past performance and incorporate into future funding decisions

- Employ predictive analytics on available data to discover nascent problems

- Align data and evaluation tools to strategic goals and utilize the data used to hold programs or providers accountable for results

Set Aside Risk Capital

In 1970, Canadian social innovator Stuart Conger catalogued thousands of policy, civic and social innovations from across the globe, looking back over several centuries (Conger, 2002). One of the trends he observed pertained to the characteristics of systems that produced major social innovations: “a basic philosophy, organization structure, and risk capital that favor experimentally adopting new methods.” In most cities today, risk capital generally comes from the private sector, whether business or philanthropy. The entrepreneurial Young Foundation in London suggests that communities can help drive more innovation by providing risk capital to innovators. Specific mechanisms include making small grants more readily obtainable, making existing public dollars more accessible to start-ups and establishing experimental centers for the express purpose of encouraging promising ideas that have not yet been tried in the public sector (The Young Foundation, 2007; 2008). Government-funded research and development occurs at the federal level—from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency to the National Science Foundation—however, R&D or innovation capital at the local level is often quite rare.

Proven but nuanced innovations face particular financial obstacles because government agencies are more likely to fund or adopt simple and inexpensive innovations. Further, strained city budgets will continue to effect downward pressure on public and political receptivity to experimenting with tax dollars on new ideas. Risk capital or innovation funds can help address both of these challenges. The authors would argue that the amount of funding available is less important than the expressed intent to commit to these three values: funding should be directed toward promising new ideas, innovators should be promised sufficient political protection to experiment and eventually to expand and new ideas require flexibility to overcome the prescriptive nature of public procurement and grant making. Government-backed innovation funds can also catalyze additional investment—or replication—from private funders. By setting an example, innovation funds can catalyze change in other city agencies, motivating them to consider or adopt new programs, innovation-related strategies or even their own R&D or innovation funds.

Bloomberg Philanthropies: Incentivizing InnovationBloomberg Philanthropies’ Mayors Challenge has encouraged hundreds of U.S. cities to develop and submit innovative local solutions to national problems. With the help of a national selection committee, five winners were chosen in March 2013. Providence won the grand prize of $5 million for an early education initiative, while Chicago, Houston, Philadelphia and Santa Monica each received a $1 million award. In addition to their vision and novelty, innovations were judged on their implementation plans and their potential for “creating measurable impact,” including their ability to replicate the model in other jurisdictions. The winners were selected from 20 finalists, based on an initial applicant pool of 305 cities from 45 states. Among the finalists was the City of Boston, whose innovation-specific work the authors highlighted in the first paper of this miniseries. Finalists attended a two-day gathering in New York City in November 2012, where they worked collaboratively and with a cadre of experts to refine and strengthen their ideas. These finalists also received individualized coaching to prepare their ideas for final submission in January 2013 (http://mayorschallenge.bloomberg.org/). |

Although the presence of innovation funds within government is still rare, examples are emerging at all levels. At the federal level, recently established examples include the White House Social Innovation Fund, the Department of Education’s Race to the Top Fund and the Department of Labor’s Workforce Innovation Fund. Some of these efforts have sought private matching dollars; all are committed to measuring outcomes and holding recipients accountable. Race to the Top is using financial incentives to encourage performance-oriented risk taking and policy innovation in states and school districts. At the state and local levels, the authors see increasing interest in innovative financing tools, such as the recently developed social impact bond, which shifts the risk of investing in social innovations from government to private funders, encouraging the allocation of public dollars to models that demonstrate results. In 2012, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts passed legislation approving social impact bonds, and New York City announced a social impact bond agreement with Goldman Sachs and MDRC (a nonprofit) to decrease youth recidivism (Weise, 2012). New York City also provides the country’s most advanced example of municipal innovation funding, the NYC Center for Economic Opportunity (CEO), which was recently recognized as the 2011 winner of the Innovations in American Government Award (Ash Center for Democratic Governance andInnovation, 2012). Established by Mayor Bloomberg in 2006 to design, implement and evaluateunique initiatives that combat urban poverty, CEO has collaborated with 28 city agencies to launch and scale up more than 50 programs and policy initiatives. CEO not only catalyzes private investment but also influences the overall policy environment within city government— encouraging other agencies to incorporate innovation as well as rigorous data collection and evaluation into their cultures. The authors write more about CEO in the third paper on implementation and measurement.

In Practice: Set aside Risk Capital

- Provide R&D funding that is flexible enough to direct funding toward new ideas; flexibility is more important than the size of the budget

- Install mechanisms to constantly monitor and evaluate, and then continue programs that show success while discontinuing programs that fail

- Extend impact of public dollars with matching private or philanthropic dollars

Eliminate Barriers

In addition to providing direct services to residents, city governments often contract, procure or otherwise fund local providers (businesses and nonprofits) to deliver critical public services. Stephen Goldsmith and others have written extensively on this “networked governance” approach, citing benefits such as increased nimbleness, efficiency and potential for innovation. Indeed, partnering or collaborating with local innovators is a strategy cited throughout the framework. Yet a notable tension in the networked governance model is how to balance the flexibility that allows for innovation with the imperative for accountability: establishing mutual goals, measuring results and tracking individual contributions (Goldsmith, 2004).

Although accountability for results is critical, often the public procurement officers responsible for holding service providers accountable are enforcers of a strict set of rules, including overly prescriptive RFPs and cumbersome reporting requirements. While such measures are intended to ensure good stewardship of tax dollars, they rarely show a particular provider’s impact. They also allow little room—and few incentives—for innovative ideas. This challenge applies to both small, new providers and to larger, established providers exploring a new program model or service. Further, costly application processes and administrative burdens like delayed payments can exclude smaller providers and favor larger providers with the resources to compete more successfully. While smaller does not always mean more innovative, increasing the pool of potential competitors should lead to improved quality. When Dace West and the Denver Office of Strategic Partnerships set out to reform the city’s purchasing of nonprofit services, they began by assessing the current system. West and her team identified many administrative hurdles, from duplication in information sharing by nonprofit applicants to overreaching monitoring and reporting requirements. They also identified a number of inefficiencies burdening the government departments directly, including inconsistent procurement training for staff, lengthy RFP development processes, significant duplication of effort in advertising opportunities and misalignment of target outcomes and goals.

To increase the amount of public dollars flowing to new ideas, governments need to rethink the rules, requirements and administrative hurdles that act as barriers to innovation for existing providers and barriers to entry for new providers. In the latter case, it must seek to level the playing field so that smaller, newer providers with innovative approaches can compete with the larger, established incumbents who repeatedly receive public dollars, often independent of performance or impact. There are examples of how government has worked to rethink procurement rules and procedures for nontraditional providers. At the federal level, the White House launched its faith-based and community initiative in the early 2000s under the leadership of John Dilulio. It began by identifying the stumbling blocks preventing (mostly small and local) faith-based organizations from accessing federal social service dollars. In response to “limited access to information, burdensome regulations and requirements, complex application processes, and bias toward incumbent providers” (Goldsmith, Georges, & Burke, 2010, pg. 80), they worked to increase outreach to the faith community, simplified application processes and encouraged funding agencies to partner with faith-based providers (Goldsmith et al., 2010, pg. 85). At the state level, Krista Sisterhen viewed her mandate as director of Ohio’s faith-based initiative as making ”doing business with government” less complicated and burdensome for local faith-based providers (Goldsmith et al., 2010, pg. 85).

At the city level, the New York City Department of Education’s iZone is working to improve the marketplace for education technology, where demand and supply are often misaligned. According to Stacey Gillett, schools have trouble following what technologies exist and determining which would work best for their students. Further, the obscurity of what is needed or effective also deters private and philanthropic funders. Meanwhile, vendors are overwhelmed by the complexities of government procurement. In response, the iZone has developed the InnovateNYC Ecosystem with funding from a U.S. Department of Education Investing in Innovation (i3) grant. The Ecosystem seeks to drive smarter investments in educational technology on behalf of schools, districts, funders and solution developers by aligning purchasing processes and stakeholder needs. It will also help the district more efficiently develop, iterate and share the impact of technology-based teaching and learning supports (Stacey Gillett, personal communication, October 11, 2012).

In Practice: Eliminate Barriers

- Assess protocols and rules in purchasing and grants that favor well-established program models and incumbent providers

- Increase information flow and decrease administrative hurdles for small providers and novel services or programs

- Increase competition by identifying inconsistencies and inefficiencies affecting funding agencies and providers

Strategy 3: Developing a Culture of Innovation

Some hurdles to innovation—such as mindsets, fears or traditions—cannot be overcome by new funding or policy reform. Thus, the third strategy focuses on the importance of helping cities develop a culture that intentionally seeks out, values and expects creativity and improvement. This shift requires a change from a culture of status quo thinking and risk aversion by elected and appointed officials and staff. Mayors have a particular influence on the culture inside government by signaling (or not) to staff that innovation will be encouraged and risk taking protected. But mayors and agency heads are ultimately responsive to residents. Thus, developing a culture of innovation requires a shift not just among city officials but also among city residents. Indeed, the greatest drivers of cultural change within a community might be the citizens, who can play a key role by raising expectations for the efficiency and effectiveness of necessary public services. Citizens can also play a role in demanding change in poorly functioning systems while forgiving some failure when it is clear that risk taking is based on the thoughtful pursuit of innovative ideas. There is also a particular role for those who utilize public services or rely on the public safety net. The authors suggest that a culture of innovation means the inclusion of clients in the design, delivery and evaluation of public services. This involvement not only can trigger innovation but also will encourage clients to take greater responsibility for their own success and self-determination.

In their framework, the authors focus on the relationships between the mayor and the city bureaucracy, between citizens and their local government and between clients and service providers. The three components of a culture of innovation are: rewarding and protecting risk taking, particularly by city leaders; building public awareness and mobilizing community support for innovation and reform; and empowering clients by increasing expectations for individual potential and responsibility.

Protect Risk-Taking

Entrepreneurs often have a sophisticated understanding of risk. Similarly, those looking to support and empower innovation must understand risk from a variety of angles: the acknowledgement and anticipation of political risk; the general aversion to risk and lack of incentives to assume risk within government; and tactics for anticipating, evaluating, underwriting and mitigating risk. Boston’s Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics, for example, protects risk takers by helping to manage relationships with the mayor, media, peers, employees and the public. If a venture is falling short of its goals, the team steps in quickly to help the innovator “navigate and manage and message” (Nigel Jacob, personal communication, June 6, 2012).

No matter the sector, an organization’s culture plays a role in determining its level of risk tolerance—and subsequently its level of innovativeness. As Kristina Jaskyte writes, leadership is critical to establishing an innovative culture—which she describes as one that empowers staff members to take risks and allows them to make mistakes—through the norms and rules that govern an organization. For example, allowing employees to share ideas within or across organizations opens the door to new thinking that, in return, can facilitate new ideas (Jaskyte, 2004). Reflecting his firsthand knowledge as a former mayor of Indianapolis and recipient of Harvard University’s Innovations in American Government Award, Stephen Goldsmith adds, “The chief executive must be willing to accept the risks, both real and perceived, and embrace change. He must encourage subordinates to generate ideas, assess feasibility, build business cases, coordinate implementation, track results and help make successful reforms stick” (Goldsmith, April 20, 2011). In practice, this includes recruiting, rewarding and protecting risk takers within an organization. It also includes mayoral mandates that reinforce the value of and need for innovation.

New York City’s and Boston’s mayors provide strong examples in this arena. They regularly choose to hire talent from outside traditional public institutions as a way to signal both internally and externally that they are seeking new ideas and new ways of operating. They also partner with innovators in the community as a way to reduce political risks or provide a degree of political cover. In NYC, Bloomberg and his schools chancellor, Joel Klein, opened 333 new public schools and more than 80 charter schools between 2002 and 2009 by matching each with a community group, civic association or other nonprofit organization (Georges, 2011). Bloomberg and Klein also engaged 500 City Year corps members for in-school mentoring and literacy assistance work in schools in the city’s most under-resourced neighborhoods—injecting enthusiasm and a culture of high expectations that government was unable to provide on its own. NYC also created the nonprofit Principal Leadership Academy as an alternative vehicle for the recruitment, training and placement of principals. In each case, the mayor and chancellor intentionally sought partnerships to mitigate political risk by leveraging private-sector creativity to develop new models and private-sector flexibility to execute those models.

Another approach to addressing political risk is to establish a team that focuses “24/7 on innovation.” Not surprisingly, these teams work best with autonomy, Goldsmith has suggested, and should be “trusted to interact with agency heads and other key officials, but neither manage nor are managed by those units they seek to influence” (Goldsmith, April 20, 2011). He notes though that these teams are not useful simply to generate new ideas; to varying degrees they also seek to change the culture across city government by, for example, offering frontline employees a safe place to pitch a cost-saving or service-improving idea that they would otherwise be afraid to suggest to their managers. The authors spoke to a number of such teams for this project, including NYC’s Center for Economic Opportunity as well as Boston’s Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics, Philadelphia’s new Office of New Urban Mechanics and San Francisco’s chief innovation officer. Bloomberg Philanthropies has also funded Innovation Delivery Teams in Memphis, Atlanta, Chicago, Louisville and New Orleans. While most of these examples are fewer than five years old and therefore too young to show evidence of best practices, all are backed by strong mayoral support, the political cover to take risks and a mandate to promote innovation across city agencies.

In Practice: Protect Risk-Taking

- Leadership should reward risk taking and make public its expectation for innovation

- Deploy a team or launch a formal initiative to focus on elevating risk tolerance and generating new ideas

- Recruit and hire innovators from, and seek partnerships with, organizations in other disciplines and fields

Mobilize Public Will

Successful innovation requires equal parts collaboration and disruption. By disruption, the authors mean a break from business as usual or altering the inertia of existing systems. As the status quo providers of public services have likely attracted powerful constituent groups, any disruption can be a politically costly endeavor. Mayors who want to drive innovation in their communities often assume the political risks, and expend the political capital, necessary for disrupting the status quo. By appealing to residents and mobilizing public will, through the bully pulpit for example, mayors can increase public tolerance for innovation or gain support for a specific reform agenda. HKS professors Mark Moore and Archon Fung explore the public’s role in encouraging innovation in a chapter in Ports in a Storm: Public Management in a Turbulent World, arguing that the way to transform a public institution is to look outside it (Moore & Fung, 2012). They view the general public as latent advocates for change within public institutions, even as valuable partners to any government official looking to innovate.

Engaged citizens can influence government policy or legislation, and the same is true for government performance. John C. Pierce, Nicholas P. Lovrich Jr. and C. David Moon studied the connection between community engagement and government performance in 20 U.S. cities and found that the level of social capital in these cities correlates closely to the quality of their government services (2002). They echo Moore and Fung in emphasizing the importance of the mobilization of public will: “Social capital underlies the capacity of citizens to mobilize on the basis of their shared concerns and thereby influence the quality of government behavior; it empowers citizens to sanction leaders and government agencies that fail to live up to their expectations” (Pierce et al., 2002). Although it’s critical to developing a local culture of innovation, community engagement can often be much easier to advocate than to achieve (Goldsmith & Burke, 2011). With the exception of the mayor, most public managers are not comfortable with the idea of engaging the public directly in supporting their work. That said, successful public innovators anticipate fear and opposition. They work to build political constituencies who will vocally support the change they are working toward, whether through digital media or traditional strategies, such as parent meetings and neighborhood organizations.

San Francisco: Community EngagementWhile digital media and mobile technologies alone are not sufficient to create or sustain meaningful community engagement, they are often central to the revival of city efforts to engage and connect residents. The Mayor’s Office of Civic Innovation in San Francisco, for example, has been at the forefront of a new generation of civic technologies improving citizens’ connections with their local government—and with each other. Efforts to create community ideation activities have included “hackathons” and online platforms like “Improve SF.” Moving forward, Chief Innovation Officer Jay Nath describes their office’s vision as playing a |

The City of Detroit provides a good example of the power of mobilizing citizens behind potentially controversial reforms. Despite the poor performance of many local schools, Detroit United Way and school leaders knew that they would need to successfully mobilize community support for their school turnaround effort. They recount, “Early on we started with a good plan... that was also easy to communicate...We built broad support for the dramatic changes we knew we needed to make” (Matthews & Tenbusch, 2011). These investments paid off when the tough decisions finally came, such as which schools to close and reopen. “When they learned of the turnaround plan, many parents feared that the new schools would not accept their children or that important decisions would happen behind closed doors without their input. We allayed those fears, and by the end of year one, parents were seeing how their children were progressing. They became our biggest champions and our most effective voices.” According to Michael Tenbusch and Johnathon Matthews, “keeping the community actively engaged in school reform is key to sustaining the political will needed to maintain progress over time” (2011).

In Practice: Mobilize Public Will

- Anticipate incumbent opposition and mobilize clients and other stakeholders into a constituency advocating for change

- Engage the public in reform efforts through new tools (digital media or crowdsourcing platforms) and old (parent groups or neighborhood organizations)

- Keep the community actively informed on innovation-specific efforts

Empower Clients

In the delivery of public services, customers cannot typically “vote with their feet” the way they can in the private market if a provider does not perform satisfactorily. Citizens often have little choice among publicly funded service providers and little opportunity to communicate preferences. Few providers ask their “customers” for feedback or include them earlier in the design and delivery of services. Nonprofit leaders Mia Birdsong and Perla Ni recently described how “the stereotype of low-income people as incapable and in need of guidance is deeply entrenched in the service sector. Given the dynamic of decision-making and power, it’s not a surprise that there is little interest in finding out what low-income program recipients think about the services they are receiving” (Birdsong & Ni, 2012).

The authors’ research suggests that innovative jurisdictions do not think of citizens as passive recipients. Instead they seek to empower users of city services to more actively engage with providers. In the case of basic city services such as safety, transportation and sanitation, increased citizen feedback can lead to efficiency improvements. More participation early on can help ensure that a community’s priorities and needs are better reflected. In the case of social services, promoting active engagement can help improve program efficiency. It can also empower clients to participate more actively in their own progress and ultimately achieve greater upward mobility, more self-sufficiency and less reliance on government assistance. A culture that encourages this path would actively solicit both new ideas and feedback on existing

programs from its citizens, not just from the “experts.” It would also work to ensure that citizens have more voice in the type and quality of services by offering them more choices, the way Chancellor Klein did with over 330 new public and 80 new charter schools in New York City.

Increasingly, leaders in the field of public- and social-sector innovation are discussing the connection between client feedback and client empowerment. For example, Charity Navigator is a leading evaluative tool that potential donors can use to view a range of financial and performance information about individual nonprofits in the United States. Recently the site added an evaluative section on impact measurements reported by third parties, including clients. As Charity Navigator explains, to “break out of the trap of self-reporting that has constrained the nonprofit sector, we are embedding ‘constituency voice’ as a core part of the three-dimensional rating criteria. Initially, this will mean that charities that publish rigorously collected feedback from their beneficiaries will earn a significant number of rating points” (http://www.charitynavigator.org/index.cfm?bay=content.view&cpid=1193). Birdsong and Ni cite in their article a number of other examples of organizations’ incorporating client feedback, including their own organizations as well as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the California Endowment (2012). Outside of the nonprofit-sector models, the Yelp website is a potential model for cities to evaluate because it currently allows users in 150 cities to review social service agencies.

In Practice: Empower Clients

- Instill a culture among agencies and providers that empowers clients to actively participate in their own progress toward increased independence

- Seek client or constituency feedback, directly or through providers, on service design, delivery and evaluation

- Promote choice for clients and families among providers to empower clients and help direct resources to highest performers

IV. Conclusion

In this paper, the authors proposed a framework for promoting innovation in public problem solving. They discussed each strategy and component in detail, with supporting evidence from their work and research. As noted earlier, the authors have found that many cities are in the early stages of promoting innovation in a comprehensive way. While some utilize one or more of the strategies within the framework, the authors have not yet found a single city that is utilizing all of the framework’s components, nor have they found cities utilizing a competing, comprehensive model of strategies to promote innovation. Yet rather than presenting the framework as definitive, the authors hope this series of papers will make a useful contribution to the active discourse on public innovation that is happening in mayors’ offices, corporations, community foundations and civic organizations in cities across the country. The authors hope to hear from many jurisdictions on how this framework might help them become hubs of government and social innovation.

Integral to answering this question, the authors believe, will be the ability to adapt a comprehensive and measurable approach to developing an innovative jurisdiction. Tangible objectives and indicators could help a city determine which of its activities are most effective. Further, tracking and reporting often-complicated, long-term efforts might help a city more clearly demonstrate and communicate the value of driving innovation. Finally, formal assessment and reporting might also help to maintain the legitimacy and support of an innovation-specific initiative, team or office. In the next paper, the final of this miniseries, the authors turn to implementation of the framework’s strategies, introducing a unique assessment tool that cities and communities might utilize to evaluate their progress toward improving the local landscape for innovation. This final paper also includes a brief case study on New York City’s Center for Economic Opportunity, an award-winning government innovation team, to demonstrate and test the validity of the assessment tool and framework. The paper addresses some likely challenges to implementation and concludes with an invitation to readers to help further refine the framework and to launch a conversation among cities that will help improve their local landscapes for innovation.

References

Alvord, S. H., Brown, D., & Letts, C.W. (2004). Social entrepreneurship and social transformation: An exploratory study.

Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 40 (3), 260–282.

Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation. (2012, February 12). Center for Economic Opportunity-Wins-Harvard-Innovations-in-American-Government-Award Balfanz, J., & Emerman, J. (2011, August 1). The innovators of tomorrow (and yesterday).

Governing.com [Web log post]

Retrieved from http://www.governing.com/blogs/bfc/nurture-innovators-tomorrowyesterday.html

Behn, R. D. (2012). PortStat: How the Coast Guard could use the PerformanceStat leadership strategy to improve port security. In J. D. Donahue & M. H. Moore (Eds.).

Ports in a storm: Public management in a turbulent world. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Birdsong, M., & Ni, P. (2012). Get feedback.

Stanford Social Innovation Review 10(3).

Retrieved from http://greatnonprofits.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Summer-2012_Get-Feedback-1.pdf

Bloom, P., & Dees, G. (2008). Cultivate your ecosystem.

Stanford Social Innovation Review, 6 (1), 47–53.

Borins, S. (1998).

Innovating with integrity: How local heroes are transforming American government. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Casson, M., & Della Giusta, M. (2007). Entrepreneurship and social capital: Analyzing the impact of social networks on entrepreneurial activity from a rational action perspective,

International Small Business Journal, 25 (3), 220–244.

Conger, D. S. (2002). Social inventions.

The Innovation Journal.

Retrieved from http://www.innovation.cc/books/social-inventions-isbn.pdf

van Duivenboden, H., & Thaens, M. (2008). ICT-driven innovation and the culture of public administration: A contradiction in terms?

Information Polity, 13, 213–232.

Evans, D., & Weidman, J. (2011, July 12). Growing network: Fresh Food Financing Initiative.

Project on Social Innovation

[Web log post].

Retrieved from http://socialinnovation.ash.harvard.edu/growing-network-fresh-food-financing-initiative

Georges, G. (2011, May 24). Innovation via strong executive leadership.

Project on Social Innovation.

Retrieved from http://socialinnovation.ash.harvard.edu/innovation-via-strong-executive-leadership

Gillett, S. (2012, March 12). Building a culture of r&d in government.

Project on Social Innovation [Web log post].

Retrieved from http://socialinnovation.ash.harvard.edu/building-a-culture-of-rd-in-government

Goldsmith, S. (2004).

Governing by network: The new shape of the public sector. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Goldsmith, S. (2011, April 20). Fostering an innovation culture.

Governing.com [Web log post].

Retrieved from http://www.governing.com/blogs/bfc/fostering-innovation-culture.html

Goldsmith, S. (2011, August 17). Grassroots-powered innovation.

Governing.com [Web log post].

Retrieved from http://www.governing.com/blogs/bfc/community-innovation-collaboration-resources-grassrootsnew-york-city.html

Goldsmith, S., & Burke, T. G. (2011). Ignore citizens and invite failure.

National Civic Review, 100 (1), 14–18. doi: 10.1002/ncr.20043

Goldsmith, S., Georges, G., & Burke, T. G. (2010).

The power of social innovation : How civic entrepreneurs ignite Community Networks for Good.

San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Jaskyte, K. (2004). Transformational leadership, organizational culture, and innovativeness innonprofit organizations.

Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 15 (2), 153–168.

Kania, J., & Kramer, M. (2011). Collective impact.

Stanford Social Innovation Review, 9 (1), 36–41.

Retrieved from http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/collective_impact

Kurland, J. (2010, September 30). Can the poor help themselves? Social innovation in Boston.

Governing.com [Web log post].

Retrieved from http://www.governing.com/blogs/bfc/poor-help-themselves.html

Matthews, J., & Tenbusch, M. (2011, September 6). Turning around dropout factories.

Governing.com [Web log post].

Retrieved from http://www.governing.com/blogs/bfc/michigan-collaborative-effortturn-around-lowest-performing-schools.html

Minniti, M. (2008). The role of government policy on entrepreneurial activity: Productive, unproductive, or destructive?

Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 32 (5), 787.

Moore, M. H., & Fung, A. (2012). Calling publics into existence: The political arts of public management. In J. D. Donahue & M. H. Moore (Eds.).

Ports in a storm: Public management in a Turbulent World. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Pierce, J. C., Lovrich, Jr., N. P., & Moon, C. D. (2002). Social capital and government performance: An Analysis of 20 American cities.

Public Performance & Management Review, 25 (4), 381–397.

Root Cause. (2007). Social entrepreneurship and government: A new breed of entrepreneurs developing solutions to social problems. In The Small Business Economy: A Report to the President, 2007 for The Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy. Boston, MA: A. Wolk.

Retrieved from http://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/report-wolk.pdf

Weise, K. (2012, August 2). The test case behind Goldman’s investment in jail inmates.

Bloomberg BusinessWeek.

Retrieved from http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2012-08-02/the-test-case-behind-goldmans-investment-injail-inmates

The Young Foundation. (2007). Social innovation: What it is, why it matters and how it can beaccelerated,” London, UK: B. Sanders, G. Mulgan, R. Ali, & S. Tucker.

Retrieved from http://youngfoundation.org/publications/social-innovation-what-it-is-why-it-matters-how-it-can-be-accelerated/

The Young Foundation. (2008). Transformers: How local areas innovate to address changing social needs. London, UK: G. Mulgan, N. Bacon, N. Faizullah, & S. Woodcraft.

Retrieved from http://www.youngfoundation.org/publications/reports/transformers-how-local-areas-innovate-addresschanging-social-needs