Shantytowns and settlements in the City of Buenos Aires

Source: La Nueva Newspaper1

Summary

According to data obtained from the National Survey of Low-income Neighborhoods (Decree n. 358/2017), in Argentina there are more than 4,000 low-income neighborhoods -- commonly referred to as slums, shantytowns, settlements, or informal urbanizations -- with varying degrees of precariousness and overcrowding and, in most cases, with a high deficit in formal access to public services and irregular land tenure. This situation affects people’s quality of life as it gives rise to poverty, segregation, marginalization, and social fragmentation.

Among all low-income neighborhoods surveyed nationwide, about 1,000 are located within the territory of the City of Buenos Aires and its suburbs. Most of them fall within the service coverage area of Agua y Saneamiento Argentinos S.A. (AySA), which means a big challenge for this state company.

In this scenario, the national government has suggested several courses of action to identify the vulnerable and to get started with the basic works required to ensure access to drinking water and sanitation in this type of neighborhoods. It has also demanded AySA to review its criteria for residents’ connection to the network.

In the present article, we will explore the challenges involved in service provision and expansion in low-income neighborhoods --- as a result mainly of the characteristics of their urban infrastructure -- to then present the main innovative actions and changes that AySA could put to work to comply with the government's priority policy aimed at poverty reduction and universal access to water and sanitation services in urban areas.

Introduction

According to the latest data provided by the World Banks Water and Sanitation Program (WSP), 36 million people in Latin America and the Caribbean have no access to improved water2 and 110 million have no access to improved sanitation3 (WSP, 2017). Universal access to drinking water and sanitation poses one of the biggest challenges for Latin America and the world to provide its inhabitants with such a key vital element.

Water and sewer services expansion not only positively impacts the heath of the poor as it protects them from diseases carried by unsafe water for human consumption and hygiene, but also their household economy as it reduces the cost entailed by the alternative provision of these services such as installing wells, water pumps, and septic tanks, hiring tanker and vacuum trucks, purchasing bottled water, and hauling water from public taps, among others. Besides, the absence of sanitary infrastructure mainly affects low-income, vulnerable residents, thus deepening already existing social inequalities. Increasing the coverage of these services offers the possibility of reducing income inequality in the medium and longterm.

Over the last few decades there have been various initiatives worldwide to put water and sanitation at the center of the international agenda, thus enabling the recognition and commitment of countries to increase coverage and to invest in the sector. Along those lines, the United Nations (UN) formally recognized the human right to water in 2002: “The human right to water entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible, and affordable water for personal and domestic uses.” (CESCR, 2002). A few years later, this notion was strengthened even further through the declaration of the United Nations General Assembly whereby the UN explicitly recognized the human right to water and sanitation and acknowledged that clean drinking water and sanitation are essential to the realization of all human rights.

In tune with this recognition, at the beginning of the 21st century the UN set its Millennium Development Goals (MDG) -- currently referred to as Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Among other things, the proposed reduction in population without access to drinking water and basic sanitation services aims to decrease poverty levels around the world. Argentina assumed its commitment to these goals and established compliance requirements which were more stringent than international standards (Lentini and Brenner, 2012).

Also, from 2016 the country has made water a central pillar of its policy aimed at eradicating poverty through the use and leveraging of this resource. For this reason, through the Undersecretariat of Water Resources of the Nation (SSRH), the government has established the National Water Plan to address the four main axes of the water policy: waters and sanitation, adaptation to extreme climate changes (floods, droughts, etc.), water for production and, finally, energy generation from biomass. As regards the first axis, the government also established a National Plan for Drinking Water and Sanitation (NPDWAS), which intends to reach universal access to drinking water services and 75 percent sewer coverage in urban areas of the country by 2023.4

Nowadays, Argentina faces significant water coverage deficit. It is estimated that by the end of 2015 around 39.8 million people resided in urban areas, 87 percent of which had access to public water, and only 58 percent to the public sewer (SSRH, 2016). In most cases, the lack of coverage is most acute in the periphery and in low-income neighborhoods where the vulnerable live, showing that socio-spatial inequality in service distribution mainly affects low-income families (Merlinsky et al., 2012). This situation is worsened by the invisibility these social sectors face. In many cases, they are not even accounted for by national statistics, which makes it difficult to develop policies specifically adapted to these families.

In this scenario, our article explores the measures carried out by the national government to identify the residents of these low-income neighborhoods. We will then focus on the innovative mechanisms developed by AySA -- the main water and sanitation provider in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires (AMBA),5 the most densely populated area in the country, to expand service to those neighborhoods in order to reach the goal of universal access to water and sanitation in urban areas.

The present study is exploratory in scope and qualitative in its methodology. It is based on the review and analysis of secondary normative sources, mainly the National Low-income Neighborhoods Survey, the National Low-income Neighborhoods Undergoing Urban Integration Register (RENABAP), the Planning Agency (APLA), and AySA Directorate of Community Development.

Alternative Experiences of Service Expansion in Vulnerable Areas of Latin America

Demographic growth in recent years both in urban and peri-urban centers in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as in other regions of the Southern Cone, has brought about the growth of the informal city, lacking in basic urban services such as drinking water and sanitation services. This situation challenges the traditional network infrastructure in most cases.

Authors such as Allen, Hofmann, Mukherjee, and Walnycki (2017) argue that we need to forgo the idea that in the future drinking water and sanitation services in these regions will be provided by a large water supply network, as it was the case with service expansion during most of the 20th century. Instead, the solution will resemble the so-called "infrastructure archipelagos" (Bakker, 2003), where large-scale planning models will combine with daily water supply practices adapted to the reality of the settlements.

This section will review some alternative initiatives that have been adopted in recent years in different parts of Latin America to address the drinking water and sanitation deficit, especially in the most vulnerable areas. In this respect, we will refer mainly to "Water and Sanitation for Urban Marginal Areas of Latin America," a study carried out by the World Bank that gathers experiences and innovative strategies used in seven cities in the region to increase water coverage.

The first experience takes place in the city of Arequipa (Peru), where the company Servicio de Agua Potable y Alcantarillado S.A. (SEDAPAR) carries out a conventional management model of primary and secondary networks that serve the city but not the marginal areas of the metropolitan area, which are normally served through tankers. Faced with this situation, different management alternatives have been developed by civil society organizations and local governments to provide these residents with access. One of these initiatives was the creation of an Integral Development Plan (IDP) by the North Cone Defense and Integration Front, aimed at distributing water by gravity and building water reservoirs to serve the entire northern region of the city. This initiative involved the participation of its direct beneficiaries (WSP 2008, 21).

The second experience takes place in Guayaquil (Ecuador) where the private company Interagua has been responsible for the provision of water and sewer services since 2001. It provides its services via community management, holding meetings with social referents and leaders of marginal areas to assess the needs of the population. A concrete example of these actions can be seen in the Isla Trinitaria area, where the company, along with the Federation of Community Organizations of the island, has installed intra-domiciliary water and sewer connections and community pools to expand the water network to around 20,000 families, and the sewer system to 16,000.

In the case of Lima (Peru), in order to expand services to underprivileged areas, the main service provider Servicio de Agua Potable y Alcantarillado (SEDAPAL SA) has developed innovative coverage expansion programs using alternative technologies, such as condominial systems which are also used in several favelas in Brazil (Melo, 2017). These systems serve each block or group of houses -- each condominium -- instead of each housing unit (WSP 2008, 25). This allows for a shorter network than traditional systems and it better fits the topography of informal settlements, which generally does not follow the grid of the "formal” city.

In the case of Medellin (Colombia), the municipality is responsible for the provision of public water and sanitation services through Empresas Públicas de Medellín (EPM). In the city, there is almost universal coverage of both services. However, much like in the City of Buenos Aires, the biggest deficit is felt in informal settlements. These neighborhoods have been formally recognized in recent years. This has resulted in urban infrastructure improvement and land requalification, and these neighborhoods are now within the EPM coverage area. EPM has developed several mechanisms to begin to serve these residents, including the Social Procurement program, which has facilitated community participation and organization since the inception of the project to get the target population involved (WSP, 2008: 29).

These and other experiences featured in the report show that it is not only a matter of thinking of isolated solutions for the most vulnerable sectors, but of betting on integral models that contemplate differences in expansion requirements according to social sector and geographical area. The experiences analyzed also show how important social participation is as it allows for the articulation of specific needs and different government and sectoral actors responsible for service provision.

A third element that the experiences in these cities highlight is the importance of betting on innovation when it comes to designing local solutions that fit each specific situation and the fact that there is no copy-pasting of any other successful model because that would mean ignoring the local situation. Following on from that, the next section of the article will deal with the main characteristics of drinking water and sanitation services provision and the difficulties involved in the expansion of these services in socially vulnerable parts of the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires. Then, we will analyze the innovative mechanisms developed by the national government and AySA to provide services in those underserved areas.

Water and Sanitation Services in Low-Income Neighborhoods in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires

Since its inception in 2006, AySA has been responsible for water and sanitation services provision in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires (CABA) and 17 administrative districts of the Province of Buenos Aires6. As of 2016, it has incorporated within its area of concession eight new administrative districts of the third ring of Greater Buenos Aires7 which are considerably underserved (very low water and sewer coverage and very low service quality), a situation which worsens in the most marginalized areas where low-income settlements are found.

According to the latest census (2010), 76 percent of households in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires (AMBA) have access to the water network and only 57 percent have sewer drains.8 Disaggregating data geographically, great disparities in access are seen when we compare the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and the area formed by the 24 administrative districts of Greater Buenos Aires (GBA). While the city of Buenos Aires has close to universal coverage (99.6 percent of water and 98 percent of sewer service), the GBA districts show percentages well below the region’s average (67 percent and 41 percent respectively). The level of coverage within these 24 districts is heterogeneous, the municipalities furthest from the City being the most underserved.

The difference in coverage between the CABA and the 24 districts of Greater Buenos Aires illustrate the limitations that the centralized network model showed throughout the 20th century in its expansion from the center to a periphery that has become more and more degraded. These limitations are not only technical, but also political since the financing in the sector has been erratic and inefficient, preventing the service from keeping up with population growth, thus reinforcing socio-spatial inequalities in the distribution (Tobias, 2017). Socio-economic inequalities go hand in hand with this geographical difference (CABA vs. 24 districts) since it is the most vulnerable who are most likely to be underserved in their access to drinking water and sanitation.

Although in the metropolitan area many of these low-income neighborhoods are found within a so-called served area (that is, an area with existing networks nearby), they do not have formal water and sanitation networks of their own. Therefore, the residents of these neighborhoods must find alternative ways for their provision. Koutsovitis and Baldiviezo (2015) point out that most of the internal networks in these settlements (water, sewer and storm drainage) have been financed and carried out precariously by the residents themselves, without any kind of technical support or advice. We can safely assume then that the existing infrastructure in these neighborhoods is inefficient and insufficient, since the execution of the works did not contemplate the vertiginous population growth of these neighborhoods.

What is more, the quality of the water consumed by the residents of these settlements is not effectively controlled by any state agency and therefore they may be exposed to unsafe water. In the case of neighborhoods located within the served area, the inhabitants supply themselves with water using hoses (in some cases worker cooperatives have been organized) connected to the supply line the company AySA has in the periphery of these neighborhoods. There are also public taps supplied by AySA, but this forces the neighbors to haul the water to their homes.

According to García Monticelli (2017), the company faces mainly three difficulties in the expansion of drinking water and sanitation services in these neighborhoods:

The first problem has to do with the ownership of the land. Since most of these neighborhoods have irregular land tenure, there is some resistance on the part of the company to install networks in these areas because that would validate their occupation. In addition, the streets in these neighborhoods are not formally recognized by the municipality (i.e. they are not registered, they are not "public streets") and do not have the minimum 10-meter width established by current regulations. This poses considerable difficulty to service expansion. In this regard, the company has argued that according to pre-existing regulations they are not obliged to carry out the expansion works. For example, in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, the local government has agreed on a model that plans the urbanization of the plots prior to the installation of the networks.

The second problem is the insecurity reigning in these neighborhoods. The personnel in charge of the works, and even more so those in charge of operation and maintenance, are not willing to enter the neighborhoods to carry out their activities without the presence of security forces to guarantee their safety.

The third problem is the lack of economic incentive for the company to provide access in these neighborhoods given that their vulnerable residents are unable to pay the bill for services rendered.

However, as we will see in the next section, over the past year the national government and the provider have developed several innovative strategies and changes in the regulatory framework aimed at reducing these difficulties in the short and medium term in order to then advance with the provision of services in these settlements.

Social Innovation Mechanisms for Water and Sanitation Service Expansion in Low-Income Neighborhoods

Although the goal of this article is to present the recent advances in the provision of water and sanitation services in low-income neighborhoods, it is important to point out that for almost fifteen years the service provider company in the metropolitan area (now AySA and formerly Aguas Argentinas SA) has developed several programs and initiatives to meet the needs of the community, especially the most vulnerable, through the Community Development Department. Among these programs, it is worth highlighting the Participatory Management Model (MPG) and the Water + Work Program, aimed at expanding the coverage of drinking water and sanitation in deprived areas through the creation of secondary networks and the active participation of the residents.9

However, in recent years, these specific local initiatives have been complemented by others aimed at addressing the service deficit in deprived areas and in the entire concession area. In turn, as it will be shown below, recently greater articulation has been achieved between service provision in the metropolitan area (AySA being in charge) and national policies to serve low-income neighborhoods.

Surveys of Emerging Urbanizations and Low-Income Neighborhoods

During the 2013-2015 period, AySA carried out a survey of low-income neighborhoods --referred to as "emerging urbanizations" (term which includes slums, shantytowns, and settlements, but also underserved public housing)10 -- with the goal of identifying their urban, social, and technical characteristics to then be able to take specific actions for service provision (Silvi and Nuñez, 2012). This survey was conducted alongside the University of La Matanza as part of the Management Plan for Emerging Urbanizations, which in turn integrates the company’s Strategic Plan to achieve universal access to drinking water and sanitation within the concession area by 2020.

At the national level, through the Chief of Cabinet of Ministers alongside several social organizations (TECHO, CTEP, CCC, Barrios de Pie and Cáritas), between mid-2016 and mid-2017 the government carried out a National Survey of Low-Income Neighborhoods throughout the country to get updated information on the location and number of residents in shantytowns, settlements and informal urbanizations11 prior to the drafting of urban integration policies. The survey covered all districts in the country with more than 10,000 inhabitants and accounted for 4,000 low-income neighborhoods inhabited by around 3.5 million people (García Morticelli, 2017). Almost all residents in these neighborhoods lack water and sewer services (94 percent and 99 percent respectively). Among all low-income neighborhoods, 1,001 fall within the AySA concession area, which implies that 25 percent of these neighborhoods are located in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires. 153 neighborhoods (15 percent) have access to drinking water and only 38 neighborhoods (four percent) have sewer service.

Both surveys have identified the areas with the biggest service deficit, providing previously unavailable information on the characteristics of these neighborhoods and their residents. In the past year the Survey of Emerging Urbanizations developed by AySA has resorted to the data provided by RENABAP to unify criteria and take action in low-income neighborhoods within the company’s concession area.

RENABAP and Family Housing Certificate

Based on the survey of low-income neighborhoods, the national government issued Decree n. 358 creating the National Register of Low-Income Neighborhoods in the Process of Urban Integration (RENABAP), which contemplates registration of land tenure in these neighborhoods (either public or private), existing buildings and information on the people living there.

Besides RENABAP, the Family Housing Certificate was also created, which can be accessed by all people who live in low-income neighborhoods and enroll in RENABAP. This certificate is considered enough proof of the existence and validity of an address and can be used in the request of public services such as drinking water, electricity, gas and sewers, among others. The importance of this new document is given by the legal implications for the residents, who can now formally request the connection of services.

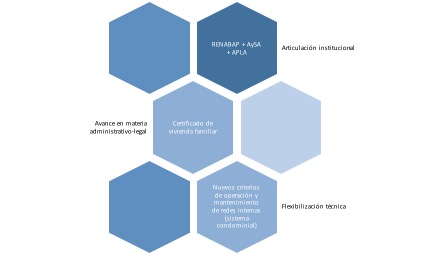

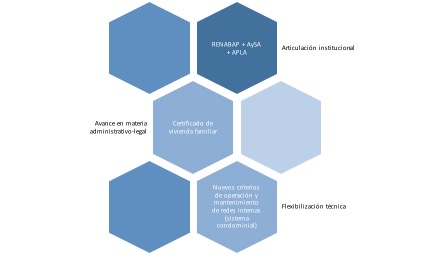

In the case of the metropolitan area, the creation of RENABAP involved the implementation of a novel institutional approach and social innovation mechanisms developed by AySA and other government agencies to address the issue. The approach is based on the articulation of participants from different areas to allow for access to drinking water and sanitation services during the process of urban integration. Equal opportunities are created by providing water and sanitation services, thus alleviating ancient deficiencies and inequalities in the access to services which separate formal and informal cities.

Table No. 1: Innovative Institutional Approach to Water and Sanitation Service Expansion

AySA and the Flexibilization of Development and Construction Criteria

As requested by RENABAP, in September 2017, the Planning Agency (Apla), a planning and control body that monitors investments carried out by the company, through resolution n. 26 passed the "Intervention Criteria for the Development and Construction of Water and Sanitation Services Infrastructure in Low-Income Neighborhoods/Emerging Urbanizations" proposed by AySA alongside competent national authorities. Thereby, the flexibilization of technical requirements for the construction of water and sanitation systems is made explicit. These new criteria that the company had to adopt as requested by RENABAP were drafted to cater for underserved areas that do not fit the traditional urban typology.

On the one hand, the flexibilization of development and construction criteria can be seen in the description of the areas the company must serve. As mentioned in the previous section, until the beginning of this year the company would not (by its own regulatory framework) provide its service on streets that were not formally registered or that did not reach the minimum width measurement established. As from now, streets just have to be of public use, have double access and a minimum width of 4m for the company to intervene.

On the other hand, and along the same lines, the definition of public roads is now more flexible so that AySA participates from the beginning of the urbanization of the settlements. This means that, from now on, the company will not only have to serve those neighborhoods that already have public roads defined and constructed, but also in the areas undergoing urbanization processes which contemplate future public roads and spaces for public use. This way, the scope of action of the company has been broadened to cover several common scenarios in these neighborhoods.

In these urbanization processes, the company must work jointly with other state agencies, such as the Nation's Undersecretary of Housing, the Nation's Undersecretariat of Habitat and the Matanza Riachuelo Basin Authority (in CABA and in 14 districts of the suburbs). In the case of the low-income neighborhoods of CABA, AySA coordinates its actions with other local agencies such as the Undersecretariat of Habitat and Inclusion, the Housing Institute of the City, the Ministry of Works, and Social and Urban Integration, among others. To date, some agreements have already been signed to work in neighborhoods such as Villa 20 and Papa Francisco, Villa Fraga, Villa 21-24 (San Blas and Tres Rosas neighborhoods), etc. (Rojas, 2017).

Table No. 2: New Public Road Criteria Adopted by AySA

Source: Rojas (2017)

However, as shown in table No. 2, in those situations in which the space between dwellings falls below the minimum required (as in the case of the "corridors" of the settlements), for the time being, actions will not be carried out by AySA, but by an operator appointed in each specific case. The operator may be a consortium of neighbors, a neighborhood council or a local cooperative, among other options, and will get resources and support from the State and technical assistance from AySA as regards the training of personnel, scheduled technical assistance and emergencies (Rojas, 2017). Although the decision to delegate the operation to an external agent has to do with AySA’s intention to avoid areas that do not fulfill the necessary requirements for service provision (even if the technical requirements have been flexibilized), it remains to be seen what the role of the company and the regulation and control entities (ERAS and Apla) will be as regards these agents, and how involved they will be in the provision of the service in those areas that overlap with the area served by the company. For some within AySA itself and others outside the company as well, AySA’s experience makes it the best equipped to deal once and for all with the deficiencies in access to drinking water and basic sanitation services in low-income neighbors and settlements.

Besides the options described to provide service in narrow spaces such as “corridors” which, as we mentioned earlier, will not be carried out by AySA for the time being, the company also contemplates the development of a provision model alongside the Inter-American Development Bank based on the condominial network system used in the favelas of Brazil. Currently, the condominial system is being developed in two pilot areas: Barrio Viaducto (in Avellaneda) and Villa del Carmen (Quilmes).

The implementation of these criteria is too recent for us to draw any general conclusions based on the advances made so far, but we can safely say that the institutional interlinkage between RENABAP, AySA and several government agencies (both national and local) for service provision in the metropolitan area -- through the creation of the family housing certificate and the flexibilization formulated by AySA to help the residents -- constitutes a novel model of social, technical and institutional innovation that provides the foundations for a more comprehensive and equitable service delivery model that contemplates and integrates the excluded population.

Conclusion

Throughout the article, emphasis has been placed on the challenges of water and sanitation accessibility in vulnerable urban populations. Firstly, we reviewed some experiences addressing this problem in the region, like the cases of Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, and Colombia, where supplying companies and governments both local and national have taken action and developed alternative provision models that resort to technological innovation and new forms of participation that involve residents and community organizations. Within this regional context, our study focused then on the specific characteristics of Buenos Aires, and analyzed what the current coverage situation is like in the metropolitan area, in particular that in low-income neighborhoods where the highest service deficit is felt.

In the second part of the article, we described the main actions carried out in the last two years by the national government and AySA to tackle the lack of service coverage in the most vulnerable parts of the metropolitan area. We also reviewed the design of several surveys for emerging urbanizations and low-income neighborhoods carried out by the company and the national government to identify and describe the housing situation of the most excluded sectors as regards service provision. Also, we described the advances made by the creation of RENABAP and the Family Housing certificate as valid legal instrument to request public services (including water and sanitation); and, finally, we presented the changes AySA had to implement in its development and construction criteria to meet the new requirements for service provision in these areas.

Based on these elements, the article set out to explore how the actions taken in informal settlements, slums, and shantytowns in recent years both nationally and locally have created an innovative approach to service provision, which, through technical but also institutional mechanisms, slowly begins to integrate the informal city into the large-scale planning as regards drinking water and sanitation services.

This policy articulates directly with the National Plan for Drinking Water and Sanitation established by the government in February 2016, with ambitious goals for the urban population by 2023: reaching coverage percentages close to one hundred percent in water service and 75 percent in sewer drains. However, these goals were set based on statistics existing at the time and were actually tailored to the formal city.

In this regard, the acknowledgement of low-income neighborhoods helped quantify, measure and take into account specific needs associated with the expansion of these services, and also to set the following goals for 2023: that 264 low-income neighborhoods of the metropolitan area shall have drinking water service and that 206 shall have sewer service. This challenging goal means connecting 111 new neighborhoods to the drinking water network and 168 more neighborhoods to the sewer network (Rojas, 2017).

The Government has decided to address the issue in an innovative way with the creation of RENABAP and the flexibilization of development and construction criteria for the sector. The challenge now will be to keep up and strengthen the policy to guarantee its full effectiveness. All of these steps are necessary but insufficient conditions to guarantee the creation of a more equitable model of water and sanitation service provision in the metropolitan area. The way these initiatives are implemented from now on will enable the expansion of water and sanitation services and thus contribute to the creation of equal opportunities, alleviating ancient deficiencies and inequalities in service access between the formal city and the informal one.

Works Cited

- Agencia de Planificación, Resolución N° 26, 2017.

- Agua y Saneamientos Argentinos – AySA, Informe Anual 2016, 2017.

- Comité de Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales –CDESC, Observación N° 15. El derecho humano al agua, 2017. www.un.org

- Allen, Adriana; Hofmann, Pascale, Mukherjee, Jenia y Walnycki, Anna. “Water trajectories through non-networked infrastructure: insights from peri-urban Dar es Salaam, Cochabamba and Kolkata”, Urban Research & Practice, 10:1, 2017: 22-42

- Bakker, Karen. “Archipelagos and Networks: Urbanization and Water Privatization in the South.” The Geographical Journal 169 (4), 2003: 328–341.

- García Monticelli, Fernanda, “RENABAP: Registro Nacional de Barrios Populares”, Presentación in International Water Association Water and Development Congress & Exhibition, 16 de noviembre de 2017, Buenos Aires: 2017.

- Joint Monitoring Programme – JMP, “WASH en la Agenda 2030. Nuevos indicadores a nivel mundial para agua para consume, saneamiento e higiene.” WHO UNICEF, Organización Mundial de la Salud, 2014. www.who.int

- Koutsovitis, María Eva y Jonatan Emanuel Baldiviezo. “Los servicios públicos de saneamiento básico en los barrios informales: 300.000 habitantes de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires condenados a vivir en emergencia sanitaria”. Voces en el Fénix N° 47 (august), 2015:136-143.

- Lentini, Emilio y Brenner, Federica. “Agua y Saneamiento: Un objetivo de Desarrollo del Milenio. Los avances en la Argentina.” Voces en el Fénix. Año 3 No. 20 (november), 2012: 42-51.

- Melo, Juan Carlos “Sistema de Saneamiento Condominial. En particular, su aplicación en favelas”, International Water Association Water and Development Congress & Exhibition, Buenos Aires, 16 de noviembre de 2017.

- Merlinsky, María Gabriela; Fernández Bouzo, María Soledad; Montera, Carolina y Tobías, Melina. “La política del agua en Buenos Aires: nuevas y viejas desigualdades”. Rethinking Development and Inequality – An International Journal for Critical Perspectives. 1 (1). Pp. 49-59, 2012.

- Pírez, Pedro. “La privatización de la expansión metropolitana en Buenos Aires”. Economía, Sociedad y Territorio, vol. VI, núm. 21, mayo-agosto. Toluca: El Colegio Mexiquense, A.C, 2006:31-54.

- Poder Ejecutivo Nacional de la República Argentina. Decree N° 358, 2017.

- Rojas, Rodolfo, “Estado de Situación de los Servicios de Agua y Saneamiento en Barrios Populares”, International Water Association Water and Development Congress & Exhibition, Buenos Aires, 16th November 2017.

- Silvi, Carolina y Nuñez, Belén (2017) Relevamiento de urbanizaciones emergentes. Manual para la formación. Buenos Aires, AySA.

- Tobías, Melina, “Política del agua, controversias socio-técnicas y conflictos territoriales en el Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires (2006-2015)”. (Tesis de doctorado no publicada, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires y Université Paris 3 Sorbonne Nouvelle), 2017.

- Tova, María Solo, Eduardo Perez y Steven Joyce, “Constraints in providing water and sanitation services to the urban poor”, WASH Technical Report, N° 85, 1993.

- Undersecretariat of Water Resources of the Nation (SSRH) National Plan for Drinking Water and Sanitation (PNAPyS), Secretariat of Public Works.

- Water and Sanitation Program, Latin America and the Caribbean, 2017, www.wsp.org

- Water and Sanitation Program, “Agua y saneamiento para las zonas marginales urbanas de América Latina. Memoria del taller internacional.” Perú: Banco Mundial, 2008.

Footnotes

1"More than 810,000 families live in slums and settlements throughout the country", Diario La Nueva, news article published on May 23rd, 2017, www.lanueva.com

2Improved drinking water sources are those which by nature of their design and construction have the potential to deliver safe water. These include running water, water wells or boreholes, protected dug wells, protected springs and rainwater catchment (JMP, 2014).

3Improved sanitation facilities are likely to ensure hygienic separation of human excreta from human contact. They include the following facilities: flush/pour flush to piped sewer system, septic tank, pit latrine, ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrine, pit latrine with slab and composting toilet (JMP, 2014).

4Coverage goals will be considered accomplished if all necessary works are started before 2019.

5The national government owns 90% of social equity shares and the remaining 10% is held by AySA workers through an ownership program. Until 2006 the services were provided by a private international consortium called Aguas Argentinas S.A.

6Avellaneda, General San Martín, Lanús, Lomas de Zamora, Morón, Hurlingham, Ituzaingó, Quilmes, San Isidro, Tres de Febrero, Vicente López, La Matanzas, Almirante Brown, Esteban Echeverría, Ezeiza, San Fernando and Tigre

7The eight administrative districts are Escobar, Malvinas Argentinas, José C Paz, San Miguel, Presidente Perón, Moreno, Merlo and Florencio Varela. It should be noted that as a result the concession area of the company comprises all 24 districts of Greater Buenos Aires (GBA), with the exception of Berazategui, Escobar and Presidente Perón, which are not included within GBA according to INDEC.

8Although in its census INDEC contemplates several forms of access to the water network service (pipes inside the house, outside the house but in the yard and outside the yard), in this study we only considered the first variable.

9The Participatory Management Model (MPG) was designed within the Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Program aimed at expanding water and sanitation services in low-income neighborhoods and shantytowns. It involved the participation of many: the company (which supplied the materials and was in charge of the execution of the works), the residents (who put in their labor to carry out the expansion), the State (which facilitated the necessary logistics through the local authorities or municipalities), and the regulator (who performed the tasks of coordination and control). In 2003, the first projects were carried out and more than 50,000 inhabitants were connected to the water supply network. The Water + Work Program, which later on added the Sewer + Work program, has the specific purpose of extending the secondary supply network to neighborhoods with high social and sanitary vulnerability. Like the MPG, it involves the participation of many and the creation of new labor sources since the works are carried out by cooperatives formed by local residents and social plan beneficiaries. Through this program, implemented as from 2004 to the present (December 2016), including both finished and in-progress works, more than 3,000 km of pipes have been installed allowing for more than 270,000 new connections which mean access to drinking water for 1.3 million inhabitants (AySA, 2017).

10AySA considers as Emerging Urbanizations (UREM) those neighborhoods formed by at least eight houses either grouped or contiguous, in any of the three types mentioned: slums or shantytowns, settlements or public housing.

11The definition adopted by the survey considers a low-income neighborhood when there is a minimum of eight families grouped or contiguous, in which more than half of its inhabitants do not have title to the land nor regular access to at least two of the basic services (water network, electrical power networks with home electricity meter and / or sewer network).