Where sustainability was once solely the domain of environmental activists, it now captures the attention of leaders in government, industry, and the community as a fundamental determinant of our wellbeing. While governments around the world are coalescing their efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change, minimize pollution, and address resource scarcity, these are often inconsistent and inadequate to address the sheer scale of the challenges, creating uncertainty and risk for business and communities. This reflects the nature of government and its need to balance the vast and varied interests of the electorate, while maintaining its stewardship of economic performance. Into this gap steps industry and our communities, whether for commercial or altruistic reasons, bringing their essential expertise and a new set of incentives to drive the needed change for sustainability.

In the State of Victoria, Australia’s second most populous, with six million people, sustainability has presented these same challenges. This article uses the example of Sustainability Victoria (SV), a state government environmental agency, and its experience working with the waste and resource recovery sector, to demonstrate innovation in government interventions to minimize the diversion of waste to landfills and maximize resource recovery. With a remit covering waste and resource recovery, climate change, and resource and materials efficiency, SV is well-placed to identify the challenges to realizing sustainability outcomes.

With bipartisan support, SV has trialled and implemented new forms of intervention, with both funding and expertise, to ensure its skillset, and that of the non-government and private sectors, is best utilized in the support of resource recovery. Part of this process is an assessment of SV’s capabilities, as well as those of others, and how the two might interact to deliver a better outcome. Recognizing this difference in skills and capabilities may seem obvious and relatively minor. But government’s role in society has changed over the past 70 years, from controllers of industry to its enablers. A change of mindset on these roles takes time. As industry emerges as the critical ingredient of a sustainable future, it is incumbent on us to work together to deliver on sustainability.

Victoria’s approach has been incremental and evidence-based. To start, a taskforce undertook a review of Victoria’s waste and resource recovery sector to determine the options on how to support its development. Consequently, SV developed a suite of strategies to both push and pull for resource recovery, including establishing an investment facilitation service to support the local resource recovery sector to overcome barriers to investment.

Launched in 2015, this service’s objective is to facilitate projects that increase Victoria’s resource recovery, by: promoting opportunities in the sector; supporting business case development; and coordinating the government response to, and support for, resource recovery projects. As a dedicated offering to the resource recovery industry, the service operates with an open-door policy to ensure it engages with as many stakeholders as possible, including project proponents, technology and engineering suppliers, waste generators, councils, communities, and end-users.

By April 2018, this service has engaged with more than 240 distinct resource recovery proposals for Victoria, rapidly increasing SV’s understanding of the sector from an industry perspective. In addition, the service engaged the financial sector, initially concentrating on superannuation funds and some of Australia’s largest retail banks. This engagement enabled SV to collate and analyze data from across the resource recovery investment community to inform government interventions in the sector.

Three issues became apparent:

- There is plenty of capital available to allocate to bankable resource recovery projects;

- The pipeline of bankable resource recovery projects for financiers to consider was insufficient; and

- There was a clear disconnect between the scale of project required by traditional financial sources (super funds and most retail banks) and the scale of projects suitable for the Victorian market at this time.

Simply put, the traditional model of intervention, supporting investment into resource recovery infrastructure through grant programs, appears inadequate to realize Victoria’s resource recovery objectives of minimizing diversion of waste to landfills and maximizing resource recovery.

What is apparent is that there is a considerable gap in support available to project proponents during feasibility. Significant upfront costs must be borne by the proponent, with no guarantee of a return on that investment. While this impacts larger, established business to a lesser extent than smaller ones, there remains a tension within corporate structures on allocating money to “non-core” activities. However, the acute impact of upfront investment in the feasibility stages impacts smaller operators more, who often rely on cashflows from existing operations to fund these activities. For entrepreneurs, with no or minor existing cashflows, the challenge to fund this necessary stage of projects is even greater. And a feature of Victoria’s (and, likely, for most jurisdictions’) resource recovery sector is its considerable ecosystem of smaller resource recovery operators. To help them grow and improve their ability for resource recovery, they require additional investment. But to get them to an “investment-ready” state requires a new kind of intervention.

Resource recovery projects require three core elements to secure funding:

- Waste feedstock: A sufficient amount with a suitable composition for an adequate amount of time to satisfy lenders.

- A secured site: With appropriate buffer zones and within range of waste feedstocks to alleviate transport and logistics costs.

- Offtake agreement: for an adequate amount of the reprocessed product for the length of the project’s life.

While there appears to be appetite to accept some merchant risk for both waste feedstocks and recovered offtake, generally each of these three elements can be contracted to a point where a resource recovery project is bankable and investment-ready.

With the investment facilitation service now well-established, SV is using the data and intelligence on the resource recovery sector to develop new interventions. These target the feasibility stages of a project proposal, premising that, should the project demonstrate feasibility and secure (or demonstrate a path to securing) the waste feedstock, the site and the offtake agreement, then the project will then be supported by financiers.

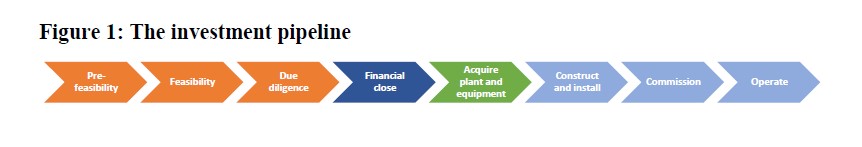

Figure 1 is a simplified illustration of the investment process and illustrates this change of approach. While financial and facilitative efforts from SV have traditionally focused on the acquisition or expansion of plant and equipment (green arrow), more recent initiatives are pushing government activity into supporting the groundwork for the project up to financial close (orange arrows). However, because financial close is dependent on negotiations between the contracting parties (the proponent and the investor), government agencies like SV have little control or influence. Instead, an intermediary stage, “investment ready.” is increasingly seen as a measure of achievement.

The interventions either developed or being actively considered include:

- The delivery of a rapid-turnaround, targeted grants program to support a range of activities that small-medium enterprises often struggle to prioritize and fund, including feasibility stages, product testing, and business case development.

- Low-interest loans/grants combination packages to support sustainability sector businesses and organizations to acquire or upgrade resource recovery equipment, known as the Social Impact Investment Fund.

- Repayable grants/loan underwrites to fund feasibility and due diligence, for repayment by financial parties at financial close (under consideration). Where projects fail to secure financial close, the information obtained by the process is made available for dissemination to inform future projects.

The challenge for using new financial tools to support feasibility stages of projects is the inherent risk of failure. Anywhere from 40-60 percent of supported projects will likely fail (not proceed to financial close). Government is traditionally risk-averse, and the feasibility stages of any project are inherently the riskiest. This explains the lack of funding for this essential project stage by either public or private sector backers. Overcoming this risk aversion is challenging, which is why traditional grant funding for plant and equipment remains. The impact of this new support strategy in resource recovery will likely take several years to determine. Resource recovery projects often have long lead times, particularly in the waste-to-energy sector where large-scale developments can take five to nine years.

But while this approach is unique for SV and Victoria in the sustainability space, it is increasingly common in other environmental agencies around the world. The Global Green Growth Institute dedicates considerable resources and expertise to “cooking” these projects to investment-ready stage, while the agency is also developing a pool of investors to whom they can pre-qualify and approach with “cooked” projects ready for investment. This “investor pool” concept is an intriguing possibility for further exploration, where investor needs and investment scopes are understood upfront by both government and project proponents, rather than treated as secondary considerations at the end of the process, as is often the case now.

Government can drive innovation in a number of ways, including through its own behavior. SV’s pursuit of new models of intervention, through both facilitative and funding tools, are worthwhile attempts to overcome barriers to investment in resource recovery, promote sustainable solutions, and deliver a more effective and long-lasting solution to our environmental challenges.