This article outlines the transformative power of having everyone at a school understand and endorse family engagement as a core strategy. The content is designed to motivate school and district leaders to consider implementing research-based family engagement practices that create inclusive and diversity-responsive relationships and collaborations within, among, and between families, teachers, school/district administrators, and other school personnel. This type of family engagement program builds effective communication bridges with families by cultivating their social and intellectual capital, thereby bringing family engagement to a higher level (Bolivar and Chrispeels). Through a well-designed family engagement program, schools ensure families gain access to, or develop, the human and cultural capital they need to fully participate in the school’s educational program with their children. Families learn of their role in reinforcing their children’s learning and of the importance of becoming partners in the schools’ reform efforts to ensure their academic success (Hong).

Educational reform literature identifies six areas in which classrooms, schools, and districts need to change if all children are to be provided with optimal learning opportunities, especially children from diverse background families who are traditionally underserved and/or underperforming. Substantial progress has been made in understanding what is needed to develop and sustain quality in five of the core reform elements, the exception is the Family, School, and Community partnership. While family involvement activities have been required in federally-funded and most state-funded educational programs since the 1960's, it is still the least understood or implemented of the key elements of educational reform (Ramirez; Domina; Wilder).

Research on building relationships with families shows that the relationships nurtured and developed with the families in the school community are of the utmost significance (Ferguson). Fostering these relationships for our communities of color; however, means honoring what they bring to school. Schools need to see diverse families as having value -- not as deficits (Olivos, Jimenez-Castellanos and Ochoa). They are a resource for other families as well as to the school. Yosso (2005) speaks to the kinds of “cultural capital” families possess and refers to it as “community cultural wealth.” Community cultural wealth includes: aspirational -- parents have aspirations for their children that helps them succeed; linguistic -- their language is rich in cultural heritage and is a connection to their families; social -- they belong to networks in their communities; navigational -- they have learned to get their needs met even though they don’t speak the language or know of the customs in their new country; and resistant -- they have a can-do attitude against all odds.

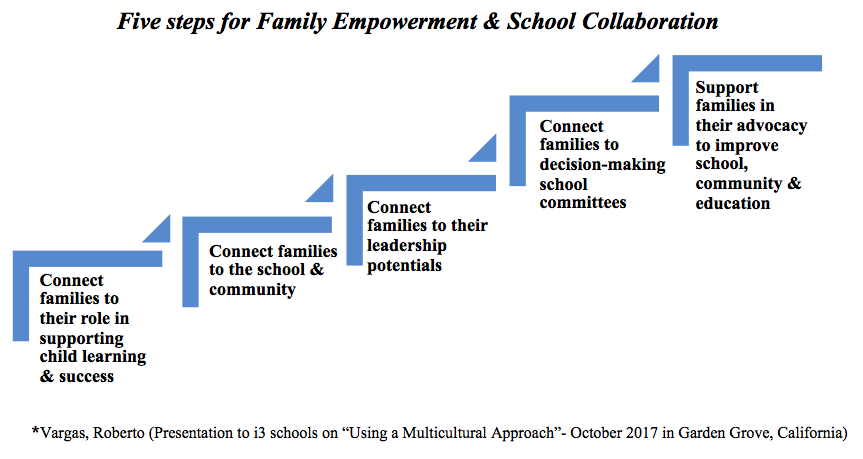

The goal for engaging families so they learn about schools and become equal partners is to develop their ability and power to accomplish results for themselves, their children, and potentially the entire school. The key is to change perceptions held by those who have traditionally held the power to either strengthen or limit engagement (Noguera; Jassis and Ordonez-Jassis; Goodall and Montgomery). There are important distinctions in the way families become partners in the school. When we engage families, we think of them as potential leaders who are integral to identifying a vision and goals for all children (Ferlazzo). Once engaged, these leaders encourage other families to contribute their own vision to the big picture, and they help perform the tasks needed to reach the established goals. Ferlazzo describes the differences between “involvement” and “engagement” of families in schools and points out that schools need to be aware of the differences and the potential outcomes of these two approaches for family engagement programs. Strong family, school, and community engagement programs reach out to families and engage them in true partnerships and challenge them to learn and apply the necessary supports for their children’s learning at home or school. Ramirez (2014) describes this as a process that gives families a sense of self (I can make a difference); a sense of place (I, too, belong at the school); a sense of purpose (I know the key role I have in the education of my children); a sense of direction (I know what I must do to ensure the academic success of my children) and a sense of possibilities (my children can be successful and go to college). It is this shared responsibility, integrated, sustained, and family strengthening approach that truly engages parents and fosters the relationships between schools and the home.

Inclusive and Partnership-Oriented Family Engagement Programs

In 2013 the U.S. Department of Education (USDE) released the Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships to guide schools in implementing effective family engagement programs. One of the premises of this framework addresses the importance of, “initiatives that take on a partnership orientation in which student achievement and school improvement are seen as a shared responsibility; relationships of trust and respect are established between home and school; and families and school staff see each other as equal partners -- creating the conditions for family engagement to flourish” (Mapp and Kuttner).

Advancing the essential opportunity and process conditions necessary to fully engage families, as outlined in the framework, makes it critical for schools to develop strategies that encourage and support a sense of community and a sense of belonging amongst the families in the school community. This speaks to the value of building a sense of “familia” -- an attitude about connection, commitment, respect, love, and purpose (Vargas; Jeynes). This approach stresses the use of culturally responsive, co-powering strategies (Vargas, Transformative Knowledge) that welcome families, especially, those who bring diverse backgrounds, languages, and are traditionally marginalized and underserved in our schools. When every family can form partnerships with the school and take on leadership roles, it has been our experience, and research on family engagement overwhelming confirms, schools transition into being better schools and show gains in student achievement (Henderson, Mapp and Johnson). The entire school community is enriched by integrating every family’s potential contributions to the school.

The supportive social relations formed while families of the same school work together provide a variety of protective functions for families who encounter many challenges. This is especially true for immigrant families who lack the support extended families offer (Valdez). Having strong family, school, and community partnerships provides emotional support, tangible assistance, and information about schooling to families, who do not know how to be engaged and what this looks like for their own realities. In addition, the connections families make with teachers, counselors, coaches, and other supportive adults at the school are important in the academic and social adaptation of students, especially English Learners, students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, and students with special needs.

The supportive social relations formed while families of the same school work together provide a variety of protective functions for families who encounter many challenges. This is especially true for immigrant families who lack the support extended families offer (Valdez). Having strong family, school, and community partnerships provides emotional support, tangible assistance, and information about schooling to families, who do not know how to be engaged and what this looks like for their own realities. In addition, the connections families make with teachers, counselors, coaches, and other supportive adults at the school are important in the academic and social adaptation of students, especially English Learners, students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, and students with special needs.

After reviewing the literature and researching family engagement practices in schools what we find is that only using one strategy, e.g., having family education sessions, does not lead to the kind of engagement that generates stronger academic achievement for every student at the school. An overall finding and conclusion points to the value of having a multi-pronged approach that not only engages families, but the entire school community where relationship-building and leadership development are the key critical elements. The following are essential components for an effective family engagement program in schools.

- Offering families an opportunity to not only get information about school activities and events, but developing their cultural/intellectual skills; increasing their knowledge about schooling and what their children are learning; and learning effective communication and advocacy skills as a foundation for becoming partners with the school -- developing social capital (Bolivar and Chrispeels).

- Building a critical mass of family leaders at the school with the knowledge and skills to engage and share their learning with other parents. Families not only learn how they can increase their children’s learning and become partners at the school, but they also participate in school leadership committees and school planning teams. They become the family ambassadors at the school reaching out to other families and engaging them in sessions that increase their knowledge and presents an opportunity for them to be engaged at the school. They become the go-to group of parents that volunteer and are available to work on meaningful projects for the school, and at the same time they encourage other families to get engaged.

- Providing professional development not only for family members, but for school leaders and other staff members on to how to work effectively and respectfully with families. Many school personnel do not have a background in family engagement or culturally responsive strategies that welcome and honor families because their teacher/administrator education program did not include this topic in their preparation (Mapp and Kuttner).

- Establishing an annual school family action plan with established goals and school activities for family engagement that are learning-outcome driven, collaborative, integrated, and focused on student achievement. This plan ensures activities supporting the instructional program take place, and are planned in coordination, with families and based on their needs.

- Ensuring the program is sustainable, systemic, and integrated into the school community. When families are integrated into the program and planning activities, this happens more readily. Monitoring and evaluating the program, with feedback from families, ensures further engagement of families who are involved in planning alongside the principal and teachers.

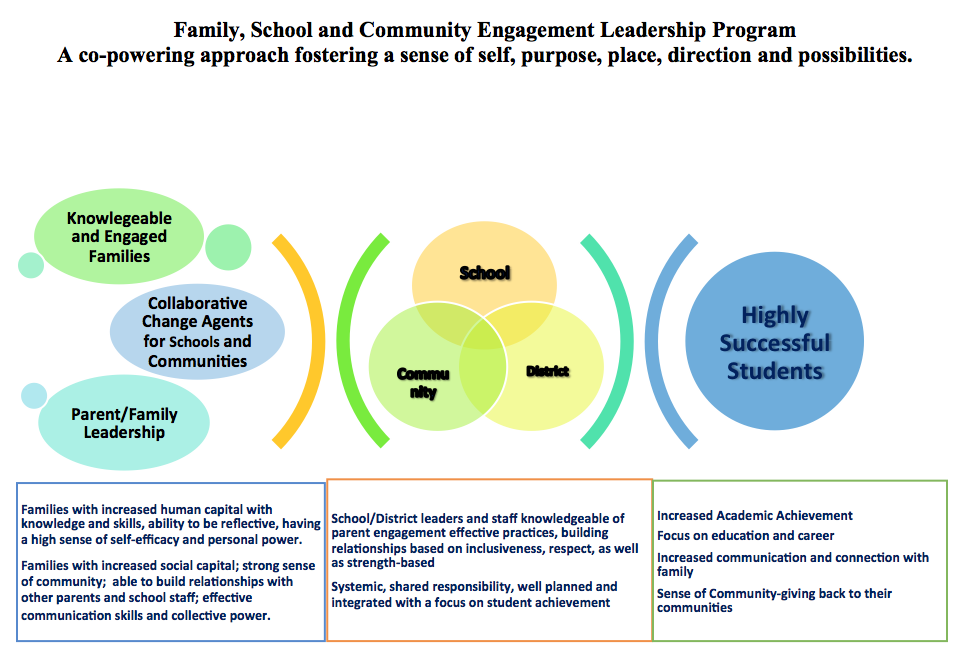

A Unifying Model for Family Engagement -- Family, School and Community Engagement Leadership Development (FSCELD)

The USDE Dual Capacity-Building Framework addresses the concept of opportunity conditions where participants (families and school personnel) come away from the learning with a desire to apply what they learn. Schools, who value what families bring to the educational setting, recognize the importance of creating opportunity conditions for everyone by having goals that build and enhance the capacity of staff and families in the 4 C areas supporting student achievement and school improvement (Mapp and Kuttner). The “4 C” areas are: a) Capability: human capital, skills, and knowledge; b) Connections: important relationships and networks -- social capital; c) Confidence: individual level of self-efficacy; and d) Cognition: a person’s assumptions, beliefs, and worldview.

The FSCELD Program1, a research-based program that is collaborative by design, has the essential key components for effective practice listed above. Unlike other family engagement programs, it deliberately fosters family engagement in the school’s context, where families have an opportunity to make a difference for the entire school community. The program features a school-based, systemic approach which engages schools and districts in building their capacity for establishing effective, meaningful, and relevant family engagement practices and strategies.

A strong feature of the program is leadership development and providing families, teachers, community liaisons, and principals the tools they need to work together as partners to improve schools and support the education of students. A five-year research study2 documented the implementation of the family engagement program. It also documented how family members, who participated in the program, increased their ability to participate in, and create a community of, support (increased social capital) from which they and other families could draw over time at each of the schools. In addition, higher levels of student academic achievement are linked to sustained family engagement in advocacy, decision-making, and oversight roles, as well as in the primary role of home teacher (Wilder; Hess). A carefully planned program, with the key features implemented, fosters the families’ ability to become integral partners in the school -- their voices, viewpoints, and experiences (increased human capital) enriches the school program and adds to the educational achievement of students.

The USDE Framework components were integrated into the design of the FSCELD program. The implementation of the program was carefully monitored using a matrix, which listed the critical components and acceptable variations of the program (Hall). As each school has their own realities, and the program is naturally different at other school sites, listing “acceptable variations” assisted the schools in seeing if their implementation of the program followed the model or had areas needing additional support and/or possible changes. The purpose of using the matrix, at least yearly, was to ensure everyone at the school had conceptual clarity about what the program looked like in practice.3 Furthermore, since planning family engagement activities is vital to an effective program, a guide and an annual plan template was developed for the schools to use. This template integrated school goals in the 4 C areas to assist the schools in maintaining the focus on the goals for the program and the process components, e.g., linked to learning, collaborative, integrated, etc. This feature ensured: 1) planned activities led to increased student achievement; and 2) there was buy-in and knowledge of activities from all stakeholders.

Documenting Success -- Building Relationships and Cadres of Parent Leaders for Our Schools

One of the major outcomes of the FSCELD program is the continued engagement of family leaders, who work with school leaders and other school personnel, to maintain and sustain the family engagement program at the school over time. The results of the program indicate that once family members develop their skills as school leaders they take on decision-making roles and work alongside the principal to engage future parents at the school. They also continue to build their own leadership capacity, as well as that of other family members at the school. Their participation has brought a rich new asset to the school. The leaders know their school and the needs of other families and they work together to meet those needs. An example is when one family had an autistic child and the parent felt it was important that other families have information on autism. The leaders worked with the principal and they planned an “Autism Day.” Information was disseminated and guest speakers provided other information on this important topic.

Two previous USDE grants from the Office of Innovation and Improvement funded the Parent Information Resource Center (2003 to 2011) that laid the foundation for securing the i3 research grant and in the development of an Awareness (18 hours), Mastery (36 hours), Expert (48 hours), and an Advanced Leadership Development (16 hours) curriculum and program design using a trainer-of-trainers model. Each of the family leadership development modules considers adult learning theory (Speck) and speaks to the essential elements of offering professional development to adults who bring their lived experiences to the learning task. Transfer of learning for adults is not automatic and must be facilitated. Coaching and other kinds of follow-up support are needed to help adult learners transfer learning into daily practice so that it is sustained. The program adhered to the following elements of adult learning theory:

- Adults will commit to learning when the goals and objectives are considered realistic and important to them. Application in the 'real world' is important and relevant to the adult learner's personal and parental needs. The “real world” in our work with parents is the improvement of academic achievement of their children, as well as developing a high level of parent satisfaction with the quality of content and usefulness of our services. Our task was to connect the dots between the knowledge of the content of our Mastery and Expert levels and the improvement of the student’s learning and the parent’s own sense of developing leadership.

- Adults want to be the origin of their own learning and will resist learning activities they believe are an attack on their competence. Thus, parent professional development needs to give participants some control over the what, who, how, why, when, and where of their learning. In terms of being the origin of their own learning, our “conocimiento” process addresses this point by situating the parent’s learning within and based on their lived experience thus underscoring their competence. We unearth the ways in which they have acquired skills and knowledge from their own lives and prompting them to formulate questions.

- Adult learners need to see that the parent professional development learning and their day-to-day activities are related and relevant. In the FSCELD program, the action plan and journal reflections are critical aspects of incorporating learning into the daily activities of parents at home, school, and community. How we follow-up with helping parents to incorporate and reflect is a key step for our participants.

- Adult learners need direct, concrete experiences in which they apply the learning in real life. Our modules give parents the opportunity to implement their action plans and get feedback from their cohort members.

- Adult learning has ego involved. Family professional development must be structured to provide support from peers and to reduce the fear of judgment during learning. Our culturally responsive approach and framework creates the opportunity for trust building and risk taking in a safe and supportive environment.

- Adults need to receive feedback on how they are doing and the results of their efforts. Opportunities for feedback is built into the activities allowing the family member to practice the learning and receive structured, helpful feedback.

- Adults need to participate in small-group activities during the learning to move them beyond understanding to application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Small-group activities provide an opportunity to share, reflect, and generalize their learning experiences. Our module structure has taken this small group need into account.

- Adult learners come to learning with a wide range of previous experiences, knowledge, self-direction, interests, and competencies. This diversity must be accommodated in planning the family professional development. To accommodate the diversity of the families and support their individual learning and at the same time promote group unity and action, the use of metaphors and sharing of experiences allows them to create an inclusive environment -- building that sense of community.

The advanced leadership sessions of the program facilitated the continued development of parent leaders at the school and district level. These school leaders are graduates of the Mastery and Expert Levels. It was noted that while they successfully completed the trainer of trainer program there was still additional skills needing attention. To meet this gap, staff developed the Advanced Leadership sessions with topics that include: 1) Building relationships with diverse background groups through effective communication strategies; 2) Using new technology tools for presentations, meetings, and for research; 3) Learning about school policies and regulations, as well as understanding roles and responsibilities of school/district leaders; 4) Developing agendas, minutes, and facilitating meetings; 5) Understanding the role of advocacy and leadership roles/responsibilities of leaders; and 6) Understanding the planning process for engagement activities and the role of parents as part of the team.

Documenting the outcomes for the research study meant that we had to have an array of measures to view what was happening at the schools. An annual parent engagement survey was given to all families at the school, as well as principal, vice-principal, teachers, and other staff. Interviews and focus groups were conducted with the principal and parent leaders to get their feedback and discuss what outcomes they experienced because of the program. In addition, at each meeting (biannual) held with the principals and district representatives, there was an opportunity for using reflection questions about what was taking place at their school to get feedback about the implementation of the program. The annual survey responses (290) for the principals, teachers, and other staff for the 2016-2017 school year, the last year of the research project, showed the following:

- From a total of 245 teacher responses, 87 percent reported that the parents at their school who are “actively engaged” have a positive impact on student learning; and 82 percent reported that these same parents have a positive impact on school improvement.

- On the annual survey on family engagement, administrators at six of the 10 schools reported an increase in relationships with parents during the last school year and three schools reported that their relationships had increased the year prior and stayed the same this year.

- 47 percent of teachers and support staff indicated their relationships with parents increased, while an additional 31 percent indicated that those relationships had increased last year and stayed the same this year.

A majority of all respondents agreed that the following statements were “a great deal like” or “a lot like” their school,

- Family programs and activities focus on student achievement so families understand what their children are learning. (Teachers 82 percent, Staff 96 percent, and Principals 100 percent)

- Families and staff have opportunities to learn together how to collaborate to improve student achievement. (Teachers 58 percent, Staff 72 percent, and Principals 90 percent)

- Teachers and families have frequent opportunities to get to know each other at school via meetings, breakfasts, home visits, and/or class observations. (Teachers 63 percent, Staff 75 percent, and Principals 90 percent)

As a result of the project, 64 percent (157) of the teachers’ stated, “I now have a greater understanding of the importance of engaging families in our school.” Teachers, at least two per project year from each school, attended a workshop on culturally responsive practices so there were at least 80 teachers who attended the sessions offered each fall. These sessions also included other office or support staff members. The aim of these sessions was to discuss and reflect on issues that impacted school climate.

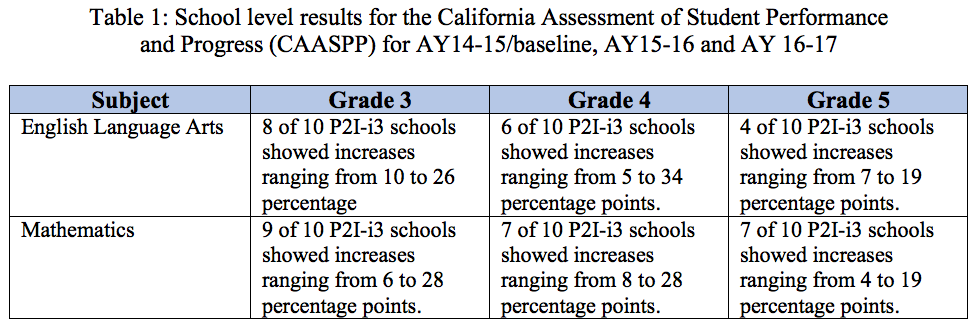

Data on the FSCELD program indicates that progress in meeting target achievement objectives for students at the 10 schools was made. The goal regarding student achievement stated -- “proficiency levels in language arts and mathematics for 3rd, 4th, and 5th grade will increase annually by four percentage points in at least six of 10 schools, as measured by spring 2015 (baseline), spring 2016, and spring 2017 state assessment data.” The following describes progress for Year Five:

Progress was also evident on the California English Language Development Test (CELDT) -- “The percentage of grade 3, grade 4, and grade 5 English Learner students scoring at Early Advanced or above on CELDT will increase by four percentage points in at least six of 10 2INSPIRE schools, as measured by spring 2015 (baseline), spring 2016, and spring 2017 scores on the California English Language Development Test (CELDT).” The external evaluators summarized CELDT data by focusing on the cohort of students that started Grade 3 in 2014-15 and looking at their progress as they moved to Grade 4 and Grade 5. The number of students tested decreased each year -- most likely as a result of students being re-designated as fluent speakers (RFEP). Secondly, the data shows that each year the cohort showed an increase in the percentage of students scoring proficient and above on CELDT. Nine of the 10 Project 2INSPIRE schools showed a 20 to 40 percentage point increase from Grade 3 to Grade 5; and only one showed a decrease.

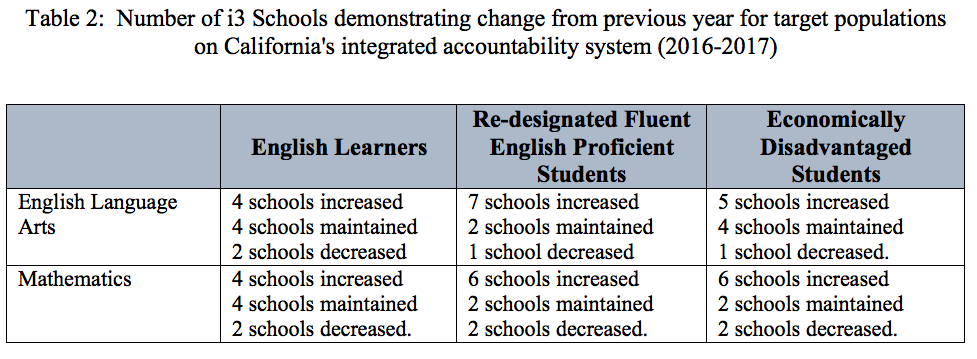

Progress made by the schools on California's integrated accountability system, that meets both state and federal requirements, also indicated positive results. Change in the accountability system is the difference between performance from the most recent year of data and the prior year’s data. The five change levels are: Increased Significantly, Increased, Maintained, Declined, and Declined significantly. The performance levels (i.e., the cut scores for Status and Change) serve as the performance standards for the state indicators.

In reviewing the progress made in engaging parents in the FSCELD Program this area also showed positive results.4 A longitudinal participant database that includes attendance and other participant information was developed by staff and evaluators to track levels of participation by participants and by site. By the end of the project, the program has: a) served 1,124 parents (unduplicated count); b) certified 652 parents at the Mastery Level; and c) certified 261 parents at the Expert Level. The results and analysis of the annual survey of families in the entire school will be completed for the evaluation report in August 2018.

One of the goals for participating families was to ensure the program quality and content met the expected outcomes for the program. Since the final report in this area is not yet complete we can look to the results in 2016 to report on the feedback provided about the leadership program from parents attending the sessions. On weekly feedback surveys, collected at the end of each Mastery level session, we included items related specifically to the objectives and learning outcomes for each session. Collectively, 97 percent (n=123) of participants “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that they had learned the concepts presented, and 98 percent (n=120) “strongly agreed” or “agreed” they were confident in applying their newly learned knowledge or skill. The Expert level surveys collected at the end of each session indicate: 97 percent (n=65) of participants “strongly agreed,” or “agreed” that they learned how to share what they learned with other parents. On the end of training questionnaire for Expert Level P2I-PLD, participants were asked to rate their level of confidence with their ability to present what they have learned to other parents. Collectively, 98 percent (n=66) of participants are “moderately” to “highly” confident that they can plan and organize a presentation for parents and others and can present information about schools to other parents.

In looking at the school context, interviews of principals (Spring 2018), who participated in the five-year research study, report the following as outcomes of the program.

- Parents are more engaged in building their knowledge (intellectual capital) and are more knowledgeable of the educational program for their children and their role in that program.

- Parents participate in meetings with the principal and are engaged in committees at the school (social capital).

- Parent are engaged in learning from and with teachers on how to reinforce what is taught to their children.

- Parents have an increased ability to be open to receive and to sharing their ideas.

- Principals have increased partnerships, better communication with parents and supportive relationships with parents.

- Parents have a greater willingness to assist/volunteer and are more involved in school activities and events.

- Parents have taken on more leadership roles (committee chairs) at the school/district.

Focus groups conducted during Spring 2018 with 60 family leaders, who participated in the FSCELD program at the 10 school sites report their participation has helped them in the following ways:

- Greater confidence for approaching teachers to discuss their children’s progress and to get suggestions from them about how they can reinforce learning at home.

- Motivated them to pursue their education (many parents have gotten their GED and enrolled in community college as well as participated in “Plaza Comunitaria” a collaboration with the Mexican Consulate to finish their primary and secondary schooling and receive their diplomas from Mexico).

- Provided them with resources that inspired them to pursue their goals established in the program, as well as, enhanced the abilities they needed for themselves and their children.

- Facilitated their participation in the leadership committees, such as School Site Council, and being representatives of the school at district meetings.

- Learned about their rights as a parent, e.g. in special education meetings.

- They are more informed and can make informed decisions and seek additional support -- e.g., they know about and understand what classes their children need for college and the importance of high school grades.

- Have greater confidence in presenting to other parents; in asking questions; in getting their needs met because of the information they received.

- Have greater expertise and knowledge to share information with other parents, getting involved in school events, tutoring students.

- They can work with the principal and teachers on supporting the school when needed.

The FSCELD program, developed under the direction of the author, implemented with the assistance of a family engagement school-site coordinator, four family specialists, and two administrative assistants were funded by the USDE Office of Innovation and Improvement’s i3 Investing in Innovation Research Program (Development grant), 2013-2018. An adaptation of the program has also received funding from foundations in Northern and Southern California and is presently being implemented in more than 25 school districts in California through contracts with individual schools and/or districts.

The family engagement program carried out in the contracts with schools use the Awareness, Mastery, Expert, and Advanced leadership curriculum. Schools seeking a contract are encouraged to include professional development for staff in family engagement practices, as well as the key planning components. The schools, however, select the services for their school sites. Even though some schools/districts do not fully implement the total FSCELD program, the results for the families, in all forms of the program, indicate parents’ sense of efficacy is enhanced as they learn both the content and to be facilitators for the program. The culturally responsive instructional approach that validates their lived experience and reinforces their strengths contributes to the success of the program. No matter which option is chosen by the schools, the schools report positive outcomes for the parents. Many of them, who participated and graduated from the program at various sites and school districts, are now participating and working as facilitators for the program at their schools or at the district level. They are sharing their knowledge and commitment to effective family engagement and making a difference not only at their schools but in many schools in California.

In speaking of the social impact this program has made we must speak of the differences we see in the families after their participation. Their sense of efficacy as parents, as role models for their children, and as active partners in the school has truly changed their lives and has had a powerful effect on their children (Jeynes). The principals and teachers, surveyed annually about family engagement practices at their school, and who participated in the research study, report that their schools have been transformed. Not only because the parents at their school know how to be -- but are -- engaged in the school. The perceptions of the parents, especially from diverse backgrounds and languages, held previously by the school staff have changed dramatically. This expected outcome fulfills the most important goal of the program. Perceptions about others interferes with and inhibits true partnerships and a willingness to work together. When respect and honor replace limiting perceptions of each other (Jeynes), real progress is made to address achievement gaps especially so evident in schools for diverse background students. It is the cumulative effect of purposeful, regular, and timely interactions between teachers and families that creates a “greater reservoir of trust and respect, increased social capital for children (and their families), and a school community more supportive of each child’s school success” (Redding, Langdon and Meyer).

Author bio

María S. Quezada, Ph.D. (2013-present) is the project director for the Investing in Innovation (i3) development grant funding research on parental engagement programs after retiring as the Chief Executive Officer for the California Association for Bilingual Education (CABE) (2000-2012) where she also served as the Director of the CA State Parent Information Resource Center (2003-2011). Previously, she was the Title VII Multifunctional Resource Center Director, and the Director for Professional Development at the Center for Language Minority Education and Research and an Associate Professor in Educational Administration at California State University, Long Beach. Dr. Quezada obtained her Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of Southern California in 1992. Her major field of study was in the area of Educational Policy, Planning, and Administration with a supplementary in Curriculum and Instruction, and an outside field in Linguistics. Dr. Quezada has provided leadership and received statewide recognition for her work in bilingual education: Bilingual Administrator of the Year (1988) for San Bernardino County; Orange County LULAC Outstanding Hispanic Educator of the Year (1991); President of CABE (1997-1999); she was recognized for her Leadership by the Los Angeles County Bilingual Directors Association in 2005; and the CABE Social Justice/Community Voice Award in 2017.

Endnotes

1The California Association for Bilingual Education, a statewide non-profit, has partnered with school districts in California to implement “Project 2INSPIRE” as the family engagement program offered to districts is called. CABE’s FSCELD program outlined for this article is a targeted school-based reform approach that engages parents from diverse and low-income communities and includes constructing a systematic, learning outcome driven, strength-based collaboration with educators, parents and the wider school community. For more information on Project 2INSPIRE interested persons can contact the Director of Family Engagement, Maria Marquez-Villa at (626) 814-4441 extension 200.

2The i3 research for the family engagement program was carried out at 10 elementary schools in three districts in Southern California. The i3 project’s research model of the program included all the key critical components for family engagement. Two research studies of the FSCELD program were funded by the USDE Office of Innovation and Improvement. One was through the Parent Information Resource Center program that included a quasi-experimental research study at 18 schools (2006-2011) in northern and southern CA and the most recent an i3 Investing in Innovation research study (2012-2018) at 10 schools in southern California.

3The research design for Project 2INSPIRE: Family, School and Community Engagement and Leadership Development Program consists of an interrupted time series design without a district-level comparison group. The outcomes from this research study allowed us to look at changes within each of our participating schools (i.e., percent of 3rd graders testing proficient before the project started and before it reached capacity compared to percent of 3rd graders testing proficient beginning in spring 2016), but we were not able to make any comparisons between our 10 treatment schools as part of this study. The preliminary year five annual survey results are reported. The project staff and external evaluators are completing the final performance, evaluation and research reports scheduled for completion by September 2018.

4 In Year 5 significant changes involved principal changes in one school. This school has had three principals during the five years of the project, another school had a principal change in year 4 and two districts had Superintendent changes. Another issue staff worked through was recruitment of family members for the Leadership Development program. In all three districts there were competing programs that impacted the recruitment efforts of project staff to enroll parents in the program. In the end, however, the parents graduating from the FSCELD program became facilitators for the other programs at the school sites—this highlights the preparation they received in the leadership program that uses a trainer-of-trainers model.

Works Cited

Bolivar, Jose M. and Janet H. Chrispeels. "Enhancing Parent Leadership Through Building Social and Intellectual Capital." American Educational Research Journal (2010): 1-35. http://journals.sagepub.com.

Domina, T. "Leveling the Home Advantage Assessing the Effectiveness of Parenatal Involvement in Elementary School." Sociology of Education Vol 78 (2005): 233-249.

Ferguson, Chris. Organizing Family and Community Connections With Schools: How Do School Staff Build Meaningful Relationships With All Stakeholders? A Strategy Brief of the National Center for Family and Community Connections with Schools . Austin, Texas : Southwest Educational Development Laboratory , 2005.

Ferlazzo, L. "Parent Involvement or Parent Engagement." May 2009. http://learning first.org. 2012.

Goodall, J and C. Montgomery. "Parental Involvement to parental engagement: a continuum." Educational Review (2014): 399-410.

Hall, G.E. "Implementation Learning builds the bridge between research and practice." The Learning Forward Journal (2011): 52-57.

Henderson, A., et al. Beyond the Bake Sale: the Essential Guide to Family-School Partnerships. New York: The New Press, 2007. Book.

Hess, G. Restructuring Urban Schools: A Chicago Perspective. New York, NY: Teachers College Press, 1995.

Hong, S. A Cord of Three Strands: A New Approach to Parent Engagement in Schools. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2011.

Jassis, P and R Ordonez-Jassis. "Convivencia to Empowerment: Latino Parent Organizing at La Familia." The High School Journal 88 no. 2 (2005): 32-43.

Jeynes, William H. "Parental Involvement Research: Moving to the Next Level." The School Community Journal Vol. 21 no. 1 (Spring 2011): 9-18.

Mapp, Karen and Paul Kuttner. "Partners in Education: A Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family–School Partnerships." 2013. U.S. Department of Education. https://www2.ed.gov. November 2014.

Noguera, Pedro. "Social Capital and the Education of Immigrant Students: Categories and Generalizations." Sociology of Education Vol 77, No 2 (2004): 180-183.

Olivos, E.M, O Jimenez-Castellanos and A Ochoa. Bicultural Parent Engagement-advocacy and empowerment. New York, NY: Teachers College Press, 2011.

Ramirez, J.David. "Building Family Support for Student Achievement: CABE Project INSPIRE Parent Leadership Development Program." Multilingual Educator 22 February 2010: 12-19.

Ramirez, J.David. CLT and Engaging Families M.S. Quezada. 18 August 2013.

Redding, S, et al. "The Effects of Comprehensive Parent Engagement on Student Learning Outcomes." Cambridge: Harvard Family Research Project, 2004.

Speck, Marsha. "Best pratices in professional development for sustained educational change." Educational Research Services (1996): 33-41. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ527481.

Valdez, G. Con respeto: Bridging the distances between culturally diverse families and schools. New York, NY: Teachers College Press, 1996.

Vargas, Roberto. Family Activism Empowering Your Community Beginning with Family and Friends. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers Inc, 2008. book.

—. "Transformative Knowledge." IN CONTEXT, A Quarterly of Humane Sustainable Culture 2008: 48-53. document.

Wilder, S. "Effects of parental involvement on academic achievement: a meta-synthesis." Educational Review (2014): 377-397. DOI: 10.1080/0013.780009.

Yosso, T. "Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth." Race, Ethnicity and Education (2005): 69-91.