Summary

Migration and the internal and external displacement of youth and families is a complex social, cultural, and political process, the implications of which can overwhelm most service delivery systems, particularly in the face of growing political volatility and shrinking pools of funding. Stories shared in counseling relating to loss, displacement, and complex trauma, both personal and historical, and the vast and seemingly impossible task of surviving through the pre- and post-migration process, often feel overwhelming and impossible to manage by clients as well as by clinicians and other providers.

La Puerta Abierta (LPA) has evolved as a community-embedded, fully collaborative, and flexible model of behavioral health care and made great strides in improving access to care for immigrant youth and families, while also challenging traditional methodologies and approaches to be more appreciative of the challenges -- and strengths -- of this shifting demographic.

History of Transnational Partnerships

The work of La Puerta Abierta (previously known as Intercultural Coalition for Family Wellness) began as an extension of a long-term relationship with several mental health programs in Latin America that aimed to address the marginalization of remote, mostly indigenous communities with little access to support for relationship health. While these communities were resourceful and tenacious in the face of many life stressors, there were multiple challenges imposed on the lives of these communities as many family members were forced to migrate to cities or other countries in search of safety and/or work. LPA developed a collaborative training model with these programs, through which a reciprocal learning process evolved over a 15-year span. As the need for improved access to mental health care became evident in the growing immigrant and refugee community in the U.S. and, more specifically, the Philadelphia region, LPA localized its work while maintaining ties to its colleagues “across the Americas.”

Hence, in 2010, LPA’s founding executive director embarked on a new phase of the organization’s work. By applying the lessons learned in its international work, LPA began building local partnerships and supporting collective efforts to promote and increase human capital of specially trained bilingual therapists and related clinical professionals to more fully respond to the growing needs of the local immigrant community. More broadly, the mission of the organization has maintained a central goal of shifting traditional systems of care to support the complex needs and circumstances of our newest community members, while staying small, flexible, and accessible.

Many Moving Parts

LPA’s constituents are comprised of youth and families who have limited or no access to clinical care due to legal, language, social, and economic barriers. Our model is “training, collaboration, and service;” through training bilingual volunteers and graduate interns, we are able to reach 200 to 300 individual youth and families annually while building the capacity of bilingual, culturally-informed professionals who are committed to serving this growing community of youth and families. Those who come through the doors of LPA represent a wide range of immigrant cultures, circumstances, struggles, and interactions with their home and new communities. In every aspect of training, supervision, and care, LPA staff, volunteers, and interns are expected to incorporate a functional understanding and appreciation for the socio-political realities that are woven through all of the life stories and presenting concerns in the counseling process. Much of this learning is a product of LPA’s close collaboration with other immigrant-serving organizations through which we are all, individually and collectively, able to tighten the safety net of supports offered in the immigrant community.

One key principle of LPA’s work is to provide the highest standard of holistic, behavioral health care while minimizing the amount of bureaucracy that could interfere with the delivery of these services and supports. Perhaps even more importantly, the model of LPA’s work is predicated on the belief that community members, including youth, have natural abilities, insights, and strengths that can be leveraged in the clinical work commonly referred to as mental health care. This culture of care is the groundwork for all aspects of LPA’s work. As such, clients referred to LPA for mental health care have doors opened to healing and also receive the clear message that they are looked upon as partners in the community-building work of LPA. A core belief in LPA’s work is that “healed people heal people,” and thus clients can be empowered to build and transform the very communities from which they come, promoting a message of stewardship of both personal and community life.

Shifting Systems of Care

There is an ever-growing need for trauma-informed, fully accessible therapeutic environments and programs that appreciate the growing diversity in our local and national communities. Yet, there is a clear misalignment between this evident need and the constraints that are typically imposed by the multiple levels of bureaucracy that are an inherent part of the behavioral health system.

This work is complicated, as are the stories and challenges that are an integral part of the work with the transnational community members LPA serves. The majority of clients who seek care through LPA come with profound legacies of suffering, including personal, family, community, and historical trauma. LPA avoids a stance of diagnosing, pathologizing, and functioning in the role of “expert,” as is often the case in more traditional mental health systems. Still, the extent and depth of suffering that is shared in the rooms of LPA is palpable.

Creating a culture of care and sustaining it at every level of LPA’s organization is of paramount importance to its work. In all venues of LPA’s work -- community-based groups, co-location in different community centers, and the partnerships that anchor them, professional and community member interactions -- LPA team members and colleagues promote and encourage an environment of “cariño” for each other, the work, and the community at large.

Prevention vs. Intervention

Prevention strategies include increasing social connection, decreasing isolation, and creating networks of support. These things are not easily quantified or measured. The population that LPA serves is an emerging yet often “invisible” demographic in this country and as such there is not sufficient data or documented evidence-based practice for how best to serve them. LPA uses qualitative evidence to confirm the impact of our work, including the informal collection of feedback and anecdotes that show improved family relationships and prevention of more serious scenarios that could result in profound consequences for individuals and families who are already vulnerable due to their status in the community. Additionally, LPA informally tracks the lives of youth who have come into the organization’s care and is able to assess the overall impact of its work through measures such as school retention and improved academic success, successful reunification with family members, lower juvenile justice involvement, increased participation in positive activities, and sustained relationships with healthy forward moving peers.

Building Upon the Work, One Relationship at a Time

LPA does not receive funding through local municipalities for its delivery of mental health services, yet it’s able to provide these supports at no cost to eligible youth and families. While LPA is volunteer-driven and grateful for the in-kind donations of office space, volunteer hours, and many supplies, the organization also relies on training and service contracts and a strong donor base to sustain and grow its financial grounding. Organizational development has required a spirit of innovation, while soliciting and valuing the input of community members present in LPA’s community spaces. Whether in the community centers that donate space for therapy and group sessions, the schools in which newcomer immigrant youth meet in groups, or the “pláticas” (talks) that take place across the state through one of LPA’s mental health/legal partnerships, relationships are the cornerstone of the organizational fabric. More recently, LPA has begun to explore and apply the use of the “promotora” model of care, providing first responder training and support to community members who have the language and life experiences to serve as resources to the local immigrant community. This is a model of work that has been used in many public health sectors in Latino communities both in the U.S. and internationally. Promotoras are community members, both adults and youth, who commit to investing their time and energy to help others in the collective effort to create neighborhood environments that are healthy and healing for everyone.

Case Example from La Puerta Abierta

This case example is representative of the many individuals and families that come into the care of LPA and reflects the ways in which LPA assesses and determines a pathway of engaging the community member(s) in a process of healing, grounding, and self agency. As described in the body of the article, LPA approaches all of its work from a position of collaborative care, while weaving in aspects of evidence-informed practice with goals that speak to relationship building, establishing trust and safety (both emotional and physical), and empowerment.

Ruddy is a 16-year-old boy from Honduras, who migrated to Philadelphia with his mother two years ago. His immigration attorney, who is representing him pro bono in an asylum petition, referred him to LPA.

Before their migration to the U.S., Ruddy’s mother suffered years of physical and emotional abuse by his father. Ruddy witnessed much of the violence. As he entered adolescence, Ruddy was forcibly recruited by local gangs and witnessed several murders and rapes in his community.

Ruddy began to be truant from school, although he was always respectful to teachers and staff when he did show up. He felt discouraged because he rarely understood what was being taught in the classroom and struggled to learn English, which compounded his frustration. His mother’s taxing work schedule made it difficult for her to get involved in Ruddy’s education; when his school contacted her about his truancy, she avoided meeting with school staff because she felt ashamed that she could not speak English and scared they would find out that she and her son were undocumented. The school perceived her avoidance as a lack of interest and expressed frustration about her lack of support for his academic success.

Ruddy felt increasingly hopeless and worthless, and often thought about going back to Honduras, even though his return could mean death. His mother was distressed by the possibility of him returning to Honduras; she worried for his safety and ruminated on the perilous journey they had endured to get to the U.S. and the large sum of money she had paid to the “coyote” who smuggled them. Despite their suffering, Ruddy and his mother found it nearly impossible to access services because of their lack of legal status.

LPA’s referral process allows the team to assess the needs of an individual or family presented to its care and to determine a method of engagement that respects the complex and particular experiences, challenges, and strengths of each client. Every referral requires a conversation with the referral source and an understanding that LPA’s work is collaborative and not merely a hand off of cases that other providers cannot/will not accommodate due to language or funding challenges.

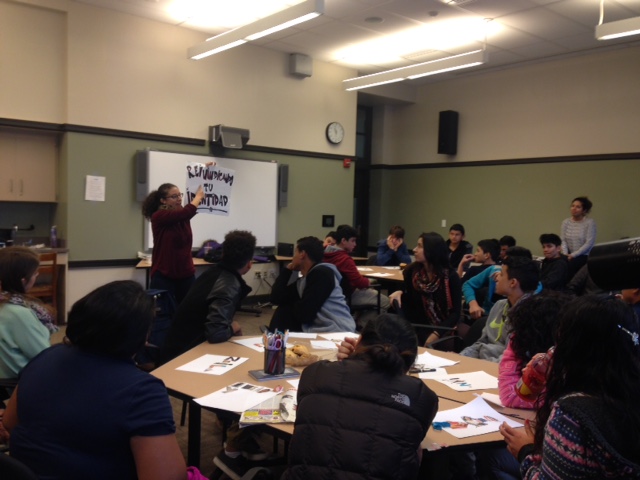

In this particular case, the LPA team, including LPA’s youth programming coordinator and a social work student intern, agreed that Ruddy would benefit from engagement in LPA’s youth programming. The safe space and relationship-focus of the youth group allowed Ruddy to meet peers who had similar experiences and embark on a pathway to healing through art-based activities designed to develop emotional language, mutual trust, and self-agency. Additionally, with the family’s explicit permission, LPA consulted with Ruddy’s school to identify in-school supports available to him and communicate regularly with his teachers in a collective effort to more fully engage him in school.

Ruddy and his mother were offered an opportunity to come to the LPA office that was convenient to their neighborhood at a time that accommodated his mother’s work schedule. A family therapy intern met with them to open a dialogue about their individual and shared experiences, during which time Ruddy’s mother became very tearful and asked him for understanding and forgiveness. Both admitted to not knowing how to talk to one another. Ruddy’s mother also expressed feeling isolated from her community and family, but saw no way out of her circumstances. LPA was conducting a women’s group with one of its partner organizations and the therapist invited Ruddy’s mother to join the group. Since her work schedule did not allow her to attend the group, the therapist arranged for one of the group members to meet with her more informally at her home, with the support and guidance of the group facilitator.

LPA’s work is conducted through a trauma-informed lens; the process of identifying trauma and beginning to heal is complex and varied. The creation of a safe and supportive network of relationships committed to community building and empowerment is a critical step in the healing process. Ruddy and his mother were able to step into this process with grace and determination, despite many challenges along the way. LPA’s model of community care offered the flexibility to navigate their complex needs while contributing to its collective learning process.

Conclusion

Therapeutic, healing spaces and communities of care are more important than ever, particularly as the number of internally and externally displaced immigrant and refugee youth and families increases. La Puerta Abierta’s organizational model represents the flexibility, innovation, and resourcefulness necessary to ensure access to healing and hopeful venues of behavioral health care for many of our most vulnerable immigrant youth and families.

Author Bio

Cathi Tillman, a licensed Social Worker and Family Therapist, is the founding Executive Director of La Puerta Abierta, Inc.