Summary

The rate of population aging is growing rapidly across the globe and requiring governments and health care systems to evolve and align with the needs of older populations. Interprofessional education implementations during training and post-training should be executed to produce teams that can best deliver integrated care. All levels of the government, from international entities to local sovereignties, should coordinate for knowledge sharing and delivery, implementation, and the creation of processes and programs to build age-friendly societies.

Article

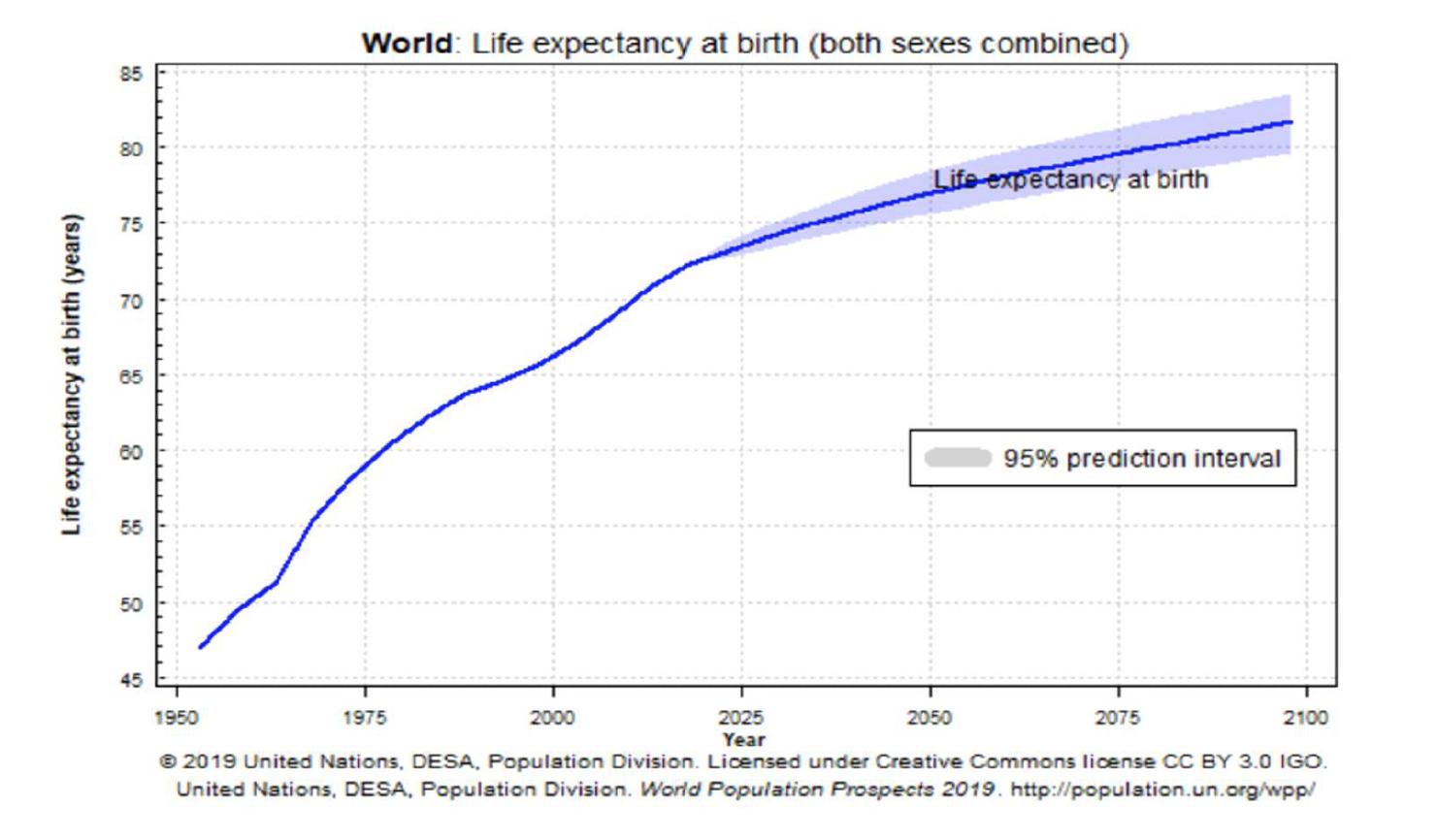

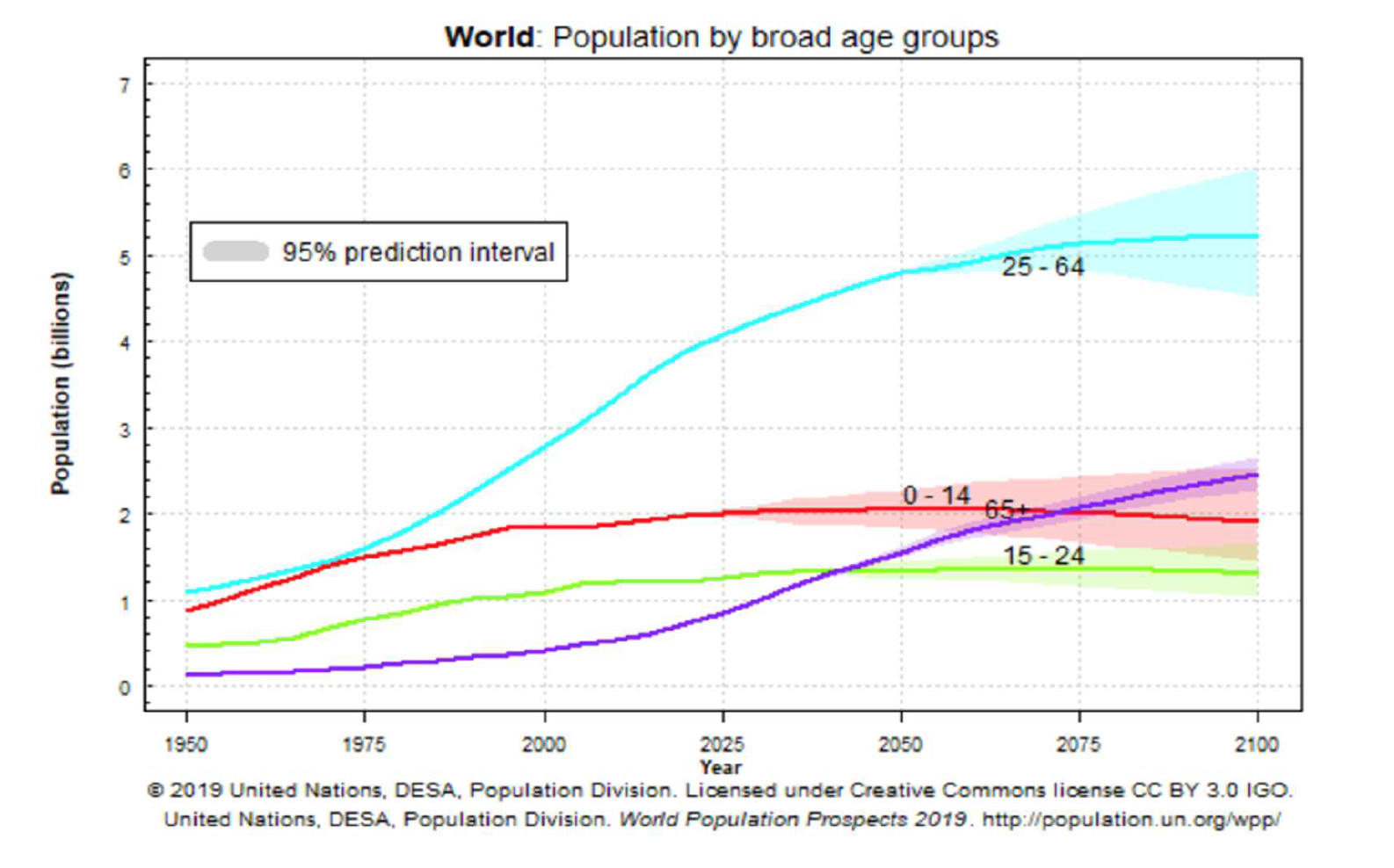

Countries across the world are facing unprecedented economic and sociopolitical challenges caused by a rapidly aging society. According to projections by the United Nations, global life expectancy is projected to increase by 15 years, from 59 years old in 1975 to 74 years old by 2025. The share of the population over 65 years old is growing rapidly. It is estimated that this cohort will overtake the size of the youth (0-14 years old) and younger population groups (15-24 years old) by 2070 (United Nations, 2019). The etiologies of the trend differ depending on the economic status of the country. In low- and middle-income countries, this trend is largely explained by the result of lower infant mortality rates and declining fertility rates. While in high-income countries, the primary factor is largely explained by extended life expectancy due to technological advances.

There are many issues that result from an aging society: rising demand for a more integrated, high-capacity health care system, along with a long-term care system. The fragmentation between care providers, institutions, and insufficient coordination of care among professionals of different backgrounds leads to a lack of communication and continuity of care, thus resulting in redundancy, high costs, and poor outcomes. Fixing the problem requires coordinating all stakeholders including health care workers, social workers, patients, and their families to provide seamless, person-centered care which can address the patients’ physical and mental health, as well as social needs.

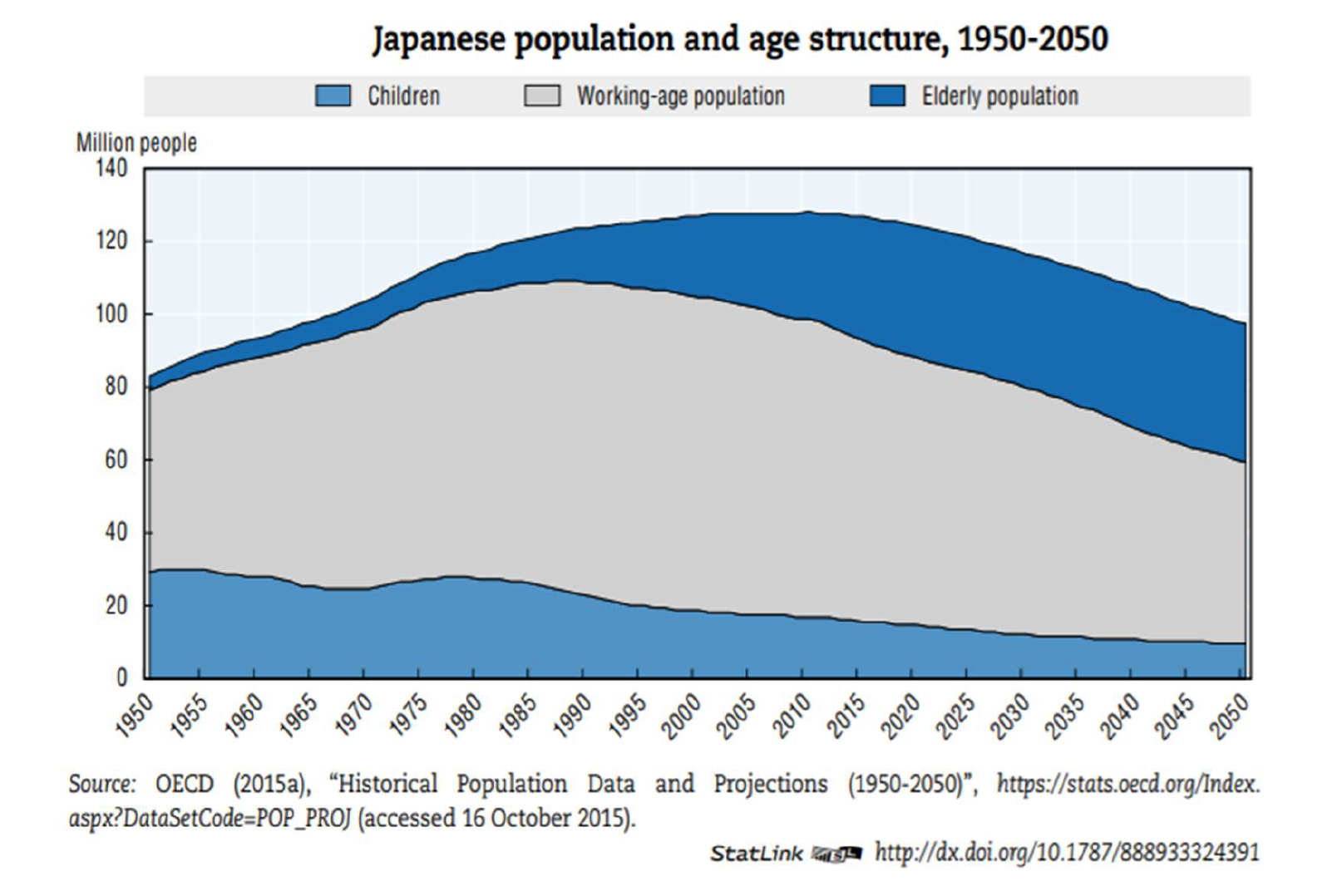

The implementation of integrated care will require major financing restructuring to support these comprehensive and large programs across different systems. For instance, Japan’s mandatory and public program “Long-term Care Insurance” (LTCI) that went into effect in 2000 provides various long-term care benefits for individuals. Some of these services include nursing homes, home helpers, and day care services with rehab. In this social insurance scheme, people aged 40 and over begin contributing to the system through premiums. Once members reach 65 years of age, they are able to access the benefits of the program. (John Campbell, 2020) Nevertheless, there is a global trend that the share of the working-age population is shrinking rapidly in comparison to that of the growing elderly population. Even with comprehensive and robust programs such as LTCI, the trend may still be a factor that causes national long-term care programs to become imbalanced and unsustainable in the long-term.

The aging population issue not only requires significant health care and long-term care system reforms, it also requires future developments to create a more age-friendly environment. A major issue confronting the elderly population is social isolation which is consistently prevalent in low-, middle-, and high- income countries across the globe. Research has shown that in the majority of Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, social support declines with age, with older people spending less time in social interactions and feeling less support than their younger counterparts (OECD, 2020). These studies suggest that the cause is urbanization and modernization forces that lead to the degradation of the former family structure that has historically provided a safety net of support and care for elderly people. Consequently, the lack of intergenerational living arrangements and family support requires larger societal transformations to supplement these support services.

This policy action paper aims to address the strategies governments and health care systems need to adopt to create a resilient society for an aging population. We aim to provide a holistic and inclusive framework for all levels of governing power as well as the health care system to solve this growing issue.

Primary Research Questions

A “Global Strategy and Action Plan on Aging and Health,” adopted in May 2016 by the World Health Assembly, focuses on strategic objectives to establish a framework for achieving “healthy aging for all.” The strategy calls on countries to commit to developing age-friendly environments, align health systems to the needs of older people, and develop sustainable and equitable systems of long-term care. It also emphasizes the importance of improved data, measurement, and research, and involving older people in all decisions that concern them. The following includes the non-exhaustive list of primary research questions that guided the research process:

What measures should health care systems adopt for a successful integrated care model -- including social, long-term care, and other services -- that will best serve people living in an aging society?

How can governments coordinate and lead various industries to support the transformation of communities and the built-environment toward one that is age-friendly and equitable?

Methodology

This policy action paper leverages a thorough review of literature, integration of expert lectures, and case studies via the TUFH Aging Society Institute, and in-depth interviews with global experts.

Analysis/Findings

The biomedical paradigm of health, which traditionally focused on biological factors as measures of health is an insufficient model to describe well-being. Rather, determinants of active aging and evaluation of well-being among the elderly should include economic, behavioral, personal, social health, social services, and physical environments (WHO, 2015). In addition, Hojman et. al recently published a study that used a novel nationally representative household survey to demonstrate human agency and dignity to also be important predictors of life satisfaction. (Hojman, Daniel & Miranda, Álvaro, 2017)

Interprofessional Education (IPE) is when “two or more professions learn about, from, and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes.”(WHO, 2010) IPE serves as a powerful tool to provide team-based, value-driven health care that can satisfy the broad and complicated needs faced by the elderly population. Training in higher education and continuing education settings have not been sufficiently responsive enough to develop an adequate interprofessional workforce (Partnership for Health in Aging, 2014).

Policy Action Recommendations

The Role of Health care Systems in Building an Aging Society

Health care systems should adopt certain process reforms in the education and training of their workforce and prepare them to operate in a complex environment. Specifically, within initiatives that can develop effective, multidisciplinary care to best support the diverse needs of an aging society.

Reforms Needed in Training for a Health care Workforce

Forms of Education and Training

Health systems should provide opportunities to facilitate and embed team-based values, collaboration, and community mindfulness among practitioners. This includes promoting self-awareness and a deeper understanding of each team member’s role in patient care. These activities can lead to cultivating interpersonal skills such as leadership, communication, accountability, and ethical attitudes. For example, after training activities, facilitators can incorporate a period for reflection on teamwork to further strengthen the development of these skills. Experiential learning practices with reflection help link theories of teamwork and team function with the practical experience: what happens, or what should happen, in the health care practice.

Contents of Education and Training

Interprofessional education should not be limited to academic spaces. For it to be an effective tool for better patient management, health care systems should continue the training in the workplace and provide interprofessional continuing education credits. More specifically, specialties such as geriatric medicine should develop specialty-specific IPE curriculum involving common geriatric diseases. This type of IPE curriculum should be included in core geriatric competencies and be a requirement for accreditation standards. Other than IPE initiatives, the use of modern technology as an education tool has been deemed promising. Adaptive technologies such as medical imaging equipment, virtual clinic, and remote patient monitoring are helpful additives to ensure patient and provider well-being. For health care systems to continue the delivery of high-quality care, training opportunities for these technologies should be readily available.

Receivers of Education and Training

IPE training and recommendations should include all patient-facing workers, not only physicians and nurses. These members are pharmacists, social workers, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, and family members who also play significant roles in the care process. During the joint training process, caregivers with different positions can develop an understanding and respect for one another.

Redefine Well-being and Develop Comprehensive Evaluations

Health care systems should redefine patient well-being by incorporating dimensions beyond traditional economic and financial measurements. The recent report, “How’s Life? 2020,” demonstrates that GDP growth for a country did not always correlate with improved well-being of the population among OECD countries. This emphasizes the need to measure beyond GDP growth as an indicator for progress. Decisionmakers need to shift their understanding of well-being to one that is multidimensional, thus deserving a multidimensional measure. Institutions such as the OECD have already begun some of these efforts. In May 2011, the organization put forward the OECD Better Life Index which included 11 topics -- including both material living conditions and also quality of life. These topics included: housing, jobs, education, civic engagement, life satisfaction, work-life balance, income, community, environment, health, and safety. Each topic is measured with various indices to ensure the multitude of dimensions that truly capture the essence of well-being (OECD, 2011). Systems around the world need to move toward measuring patient outcomes using evaluations of well-being rather than response to medical treatment. Furthermore, it is imperative for patients to be included in the formation of the well-being indicators which can create a sense of empowerment and self-sufficiency.

The Role of Local, State, National, and International Governance in Building an Aging Society

As population longevity is extended, patients face a myriad of different forms of disability and functional dependency caused by chronic degenerative diseases. It is a non-discriminatory issue that will affect many sectors of the future economy -- health care, housing, income security, transportation, and recreation. It is important for decisionmakers to realize the obvious, and not so obvious, return on investment society can have when governments invest in enabling the well-being of older people. Some of these benefits include social cohesion, innovation, and workforce participation (WHO, 2015). Building age-friendly societies also ensures the preservation of dignity each individual should be granted throughout the course of their life. Among the many stakeholders, we believe that governments play the essential role of stewardship and guidance for a unified solution to this complex problem.

Role of Local, State, and National Governments

Among the governing powers, we propose the responsibilities each level should have to maximize impact. Historically, health-related activities and the delivery of health services have occurred at the local level and regulated at this level. However, because many local governing bodies often lack the technical expertise and resources for evaluation and innovation of new interventions, we believe upstream governing bodies at the state and national level can provide the policy frameworks and resources to lower level administrations.

How to Incorporate Environmental Development and Design to Protect Aging Populations

The second critical role in governance is for national governments to incorporate inclusive, age-friendly, community design principles into the city-planning and building process of their cities. 100 Resilient Cities was established in 2013 by The Rockefeller Foundation in response to the growing physical, social, and economic challenges faced by many cities in the 21st century. Countries can reference the 100 Resilient Cities project as they develop their own policies on how to create more age-friendly environments. Through our research, we recommend the following for cities to adopt:

Implement Robust Public Transportation Networks

Design public transportation systems (buses, trains, and subways) that are elderly-friendly and will allow for safe travel. Develop alternative local transport systems to augment existing systems to provide the elderly population with access to essential locations such as clinics, rehabilitation centers, community centers, grocery stores and more.

Build Community Centers

Community centers can serve as a place of congregation for many different activities to facilitate the well-being of individuals, especially the elderly. They can be tailored to be a multipurpose space for social gatherings, medical, and educational services. One example is the Comprehensive Care Center in Toyama City, Japan which includes “a medical center, culinary school and healthy cafe, a convenience store and pharmacy, public gymnasium, and privately owned sports club” (100 Resilient Cities, n.d.). In addition to improving social wellness, community centers can ensure economic well-being by providing the elderly with a learning center for career training courses. This promotes a culture of life-long learning and develops their skills to enable them to have multiple careers throughout their lifetime -- maintaining this population’s active role in the workforce and protecting mental cognition.

Promote Social Connectivity Among Local Communities Through Various Volunteer Programs Which Can Be Activated During Pandemics, Natural Disasters, and Other Unexpected ‘Shocks’

As climate change produces stress within cities with extreme weather events, proper disaster preparation and response ensures that these natural shocks do not disproportionately affect the most vulnerable individuals. Especially the elderly which many studies have found face more adverse consequences than their younger counterparts (Cherniack, 2008). One example is the creation of the Neighborhood Disaster Prevention Associations which governments can rely on local volunteerism for adequate disaster response while fostering strong social bonds among communities. These associations are composed of local groups who are trained by the state to create community-led emergency plans and convey critical information during a disaster. They can be mobilized during a catastrophe to ensure specific groups are accounting for the elderly within the community.

Create Financial Mechanisms to Incentivize Community-based Caregiving

According to a recent report published by the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) and the National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC), one in five adults are unpaid family caregivers with an increase in this population to 9.5 million adults who have become caregivers within the past five years (Schoch, 2020). As health systems transition to community-based care and more care will be provided in homes, it is important for families, governments, and the private sector to shoulder the growing caregiving burden together. Quebec, Canada has adopted various ambitious policies to adequately address this issue. Vivre et vieillir ensemble is a program in which family members caring for their older family members receive both a tax credit and financial assistance for their care responsibilities in the home (World Health Organization, 2015, p. 220). Governments can encourage the continuation of care to be delivered in homes by creating financial incentive programs that best support this endeavor.

Role of International Community

At the international level, we advocate for the creation of platforms that will allow for transnational actors to engage in knowledge sharing, exchange of information, and uniformed data collection of age-related data.

Conclusion

The continued drive for development of innovative medical technologies is ubiquitous among modern civilizations. This means that the current aging trend will continue to be a universal and unavoidable challenge. Immediate attention for united action to build an age-friendly society is urgently needed. Health care systems need to move toward offering human-centered and integrated care. However, this challenge is not the sole responsibility of medical communities. Comprehensive and coordinated actions from other industries and sectors are also indispensable. Societies that can successfully adapt to this changing demographic and make the necessary investments to enable individuals to live longer, healthier, and meaningful lives, will create societies that are more resilient and sustainable.

Works Cited

Cherniack, P.E. The impact of natural disasters on the elderly (2008) American Journal of Disaster Medicine. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18666509/.

Farrell, T. W., Luptak, M. K., Supiano, K. P., Pacala, J. T., & De Lisser, R. (2018). State of the Science: Interprofessional Approaches to Aging, Dementia, and Mental Health. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66 Suppl 1, S40–S47. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15309

Hojman, Daniel & Miranda, Álvaro. (2017). Agency, Human Dignity, and Subjective Well-being. World Development. 101. 1-15

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2011). Better Life Index. stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=BLI

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being (2020). www.oecd-ilibrary.org//sites/9870c393-en/1/2/11/index.html.

John Campbell. (2020). Japan’s Public, Mandatory Long-Term Care Insurance System [Video]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/eCjAbgWvC20

Partnership for Health in Aging workgroup on interdisciplinary team training in geriatrics. Position statement on interdisciplinary team training in geriatrics: An essential component of quality health care for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62:961–965.

Resilient Toyama: Toyama Vision 2050 Community, Nature & Innovation. (n.d). Rockefeller Foundation: 100 Resilient Cities.

Schoch, D. Caregiving in the U.S. 2020. (2020). National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) and American Association of Retired Persons (AARP).

United Nations, Population Prospects 2019. (2019). https://population.un.org/wpp/Graphs/

World Health Organization. (2010) Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice

World Report on Ageing and Health. (2015). World Health Organization.