EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The purpose of this study is to provide additional context to publicly available estimates of state and national compensation for persons working as Direct Support Professionals (DSPs). Commissioned by three Pennsylvania associations The Alliance of Community Service Providers (The Alliance CSP), PAR (Pennsylvania Advocacy and Resources for Autism and Intellectual Disability), and Rehabilitation and Community Providers Association (RCPA), this report will largely focus on individuals working as DSPs in Pennsylvania. Specifically, this study will outline:

- The relationship between increasing DSP wages and service quality improvement,

- The cost benefit to the Commonwealth when increasing DSP wages, and

- The positive impact on the DSP quality of life by increasing DSP wages.

The study concludes that current wages require DSPs to rely on public assistance creating increased demand on the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s budget. In addition, current wages cause DSPs to leave their jobs at an alarming rate (11.9 percent vacancy rate and 26 percent staff turnover), thus compromising the quality of care to Pennsylvania’s most vulnerable individuals: children; persons with intellectual disability or autism; and persons with drug and alcohol addiction.

While the study answers several important questions about DSPs, further research is warranted in the following areas:

- A wage study to determine the extent that increased wages reduce vacancy and attrition rates and inclusion of an analysis of the impact on managers and supervisors that currently make only marginally more than the current DSP wage.

- A study on the economic impact on Pennsylvania, namely to determine the percentage of dollars spent through increased wages which are returned to taxpayers through additional tax revenues.

- A study that assesses the impact on service quality to DSP compensation practices.

- A study to determine the economic impact on the local economy when raising DSP wages.

DIRECT SUPPORT PROFESSIONAL COMPENSATION PRACTICES

Direct Support Professional (DSPs) are individuals who receive monetary compensation to “provide a wide range of supportive services to individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities on a day to day basis, including habilitation, health needs, personal care and hygiene, employment, transportation, recreation, and housekeeping and other home management related supports and services so that these individuals can live and work in their communities.” i This workforce may also be known as Client Care Workers, Residential Counselors, or Personal Care Aides, and they provide critical support to ensure that individuals who have intellectual disability, autism, and/or behavioral health concerns can “lead self-‐directed, community and social lives.”ii

In June 2003,iii per the US Department of Health & Human Services, there were 874,000 Full Time Equivalent (FTE) DSPs assisting individuals with intellectual disability, autism and/or behavioral health concerns in various settings. DSPs provide care and support to over one million Americans in need of these life-span services and supports. By 2020, it is estimated that the demand for DSPs will grow to 1.2 million due to increased life expectancy of individuals who require services; aging of the baby boomers; increased prevalence of intellectual and/or developmental disabilities; and expansion of community support systems. This constitutes a 40 percent increase in the demand of services in a little more than 17 years. With 2020 just three years away, one must speculate that the 874,000 figure substantially underestimates the current demand for services and supports.

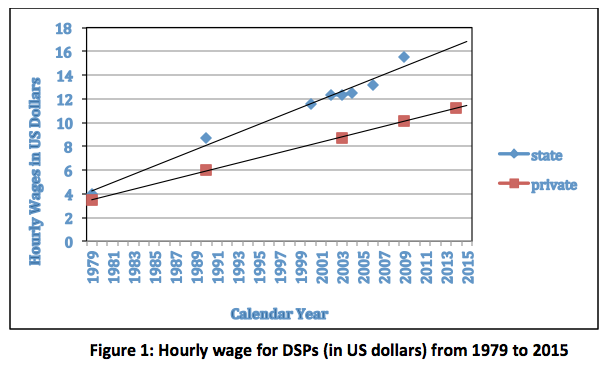

Compensation for DSPs has long been an issue of concern,iv with numerous salary surveys conducted over the past 40 years. Some studies focused on the distinction between private community and public congregate care settings (i.e. state centers), while others made no such distinctions. The primary collectors of this data have been researchers associated with the University of Minnesota. The below figure represents a summary of the DSP wage data and trends from 1979 to 2015 in both private and state settings.

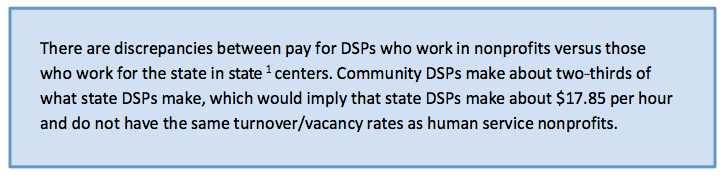

The main factor that stands out from this figure is that DSPs working for private providers in the community tend to make roughly two-thirds of the wages of similarly employed individuals who work for the state.

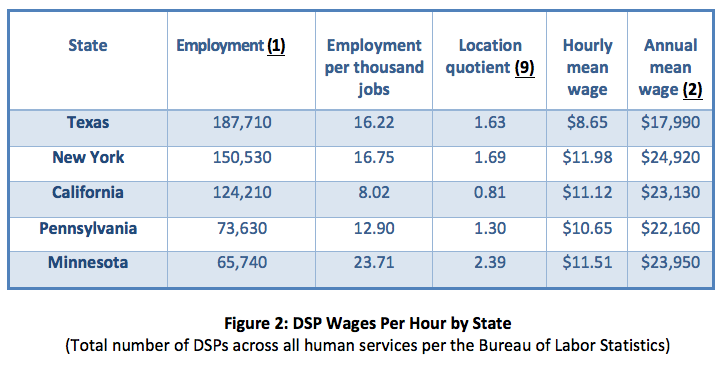

More recent studies reveal a continuing pattern of low pay being associated with the DSP position. The 2014 Minnesota studyv reported a mean hourly wage of $11.26 for private DSPs, while a systematic replicationvi conducted in Pennsylvaniavii reported a mean hourly wage of $11.26 in 2014. More current Pennsylvania dataviii revealed a modest increase to a median of $11.50 per hour for DSPs. This trend is confirmed by the Bureau of Labor Statisticsix as seen in the chart below, where 73,630 DSPs in Pennsylvania make a slightly higher annual mean wage than the national average, at $22,160.

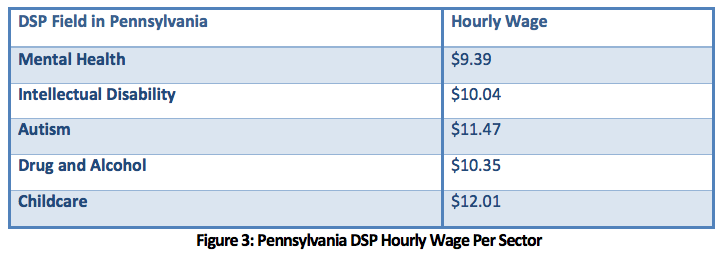

To break down the DSP workforce by type of service (e.g., intellectual disability, mental health, autism, and drug and alcohol) we pulled data from job listings and recruitment sites. According to Glassdoor,x a job listing and recruiting website, salaries for DSPs align with the aforementioned references. The hourly wages as shown in the chart below ranged from $9.39 to $12.01 per hour. DSP positions are listed at $9.39 per hour for the mental health field, $10.04 per hour for the intellectual disability field, and $11.47 for the autism field. A DSP position for drug and alcohol rehabilitation was listed at $10.35 per hour, while a DSP position for child care was listed at $12.01 per hour. These wages are consistent with national data.

WHAT IS THE FAIR COMPENSATION PRACTICE FOR DSPS IN PENNSYLVANIA?

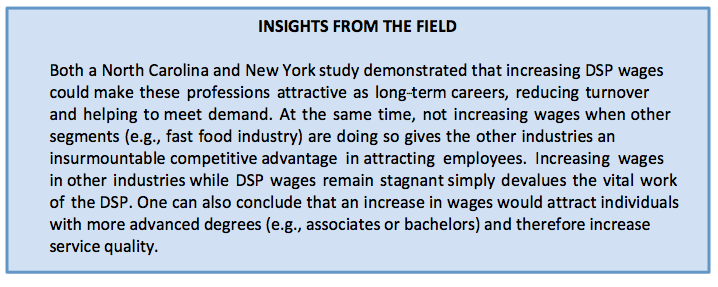

One might argue that the proper price for a DSP is the price for which people are willing to work. This is the basic Economics 101 argument, and it would pertain if Pennsylvania providers could hire enough appropriately trained staff to work as DSPs. However, given the current 11.9 percent vacancy ratexi, it is clear providers are unable to hire enough DSPs. There is also a significant concern that DSPs are not adequately prepared.xii Implied is the suggestion that even with relaxed expectations for DSPs, the field is unable to fill all vacant positions. Combined with the aforementioned rapidly growing demand for DSPs, by 2020, we are positioned to experience a latent crisis.

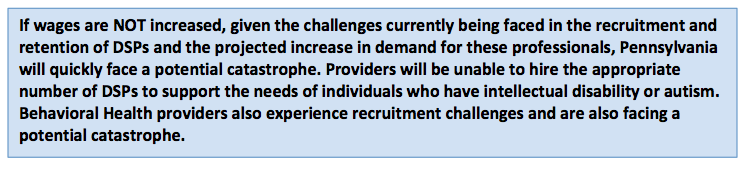

A variety of demographic trends have united to result in an increased demand for DSPs in the immediate future. Given the challenges currently being faced in the recruitment and retention of DSPs, the projected increase in demand can only result in the forecast of a potential catastrophe with providers being unable to hire the appropriate number of DSPs to support the needs of individuals who have intellectual disability, autism, and/or behavioral health concerns. It appears unlikely that providers will be able to manage the 26 percent turnover rate; fill the current 11.9 percent vacancy rate; or meet the increased demand for DSPs with the current government-suppressed wages.

Numerous studiesxii have examined factors related to Direct Support Professional turnover. Wages remain the most consistent and impactful predictor of turnover. With high vacancy rates and high turnover rates, employers become less selective, and staff quality declines. Furthermore, if higher standards were required, it could reasonably be anticipated that the vacancy rate would increase further.

These concerns extend well beyond the mere ability to fill vacant positions. The inability to fill DSP positions directly affects the quality of life for the persons supported by DSPs. The constant turnover of staff results in a transitory quality in regard to the knowledge held about consumers, as well as consumers themselves losing contact with trusted and relied-upon staff. Both turnover and staff vacancies affect the quality of care by disrupting social support networks, jeopardizing program continuity, and, ultimately, increasing the costs of providing services. The high turnover and vacancy rates require providers to offer overtime to existing DSPs to meet the needs of consumers which increases provider costs. The stress and strain on DSPs, due to working overtime hours and serving a challenging population, poses risks to consumers and overall lowers service quality. This risk has been detailed in overtime work within the nursing population.xiii

When comparing fair compensation practices to the related profession of Nursing Assistants, we note that there is current legislation in Pennsylvania, the “Nursing Home Accountability Act” (House Bill 192 and Senate Bill 1057 (Appendix A), that is based upon the Nursing Home Jobs That Pay Studyxiii that argues for “an increase of the average wage for nursing assistants to $15 per hour to meet a living sufficiency standard for an employee with one child to provide for themselves and the child without the need for public assistance.” Studies on the cross-section of public benefits and low-income workersxiv argue that wages need to rise to $19-22 per hour for individuals to no longer need to rely on public benefits, while many DSPs would need to earn as high as $32 per hour to cover expenses related to making up the difference for lost benefits.xv

When taking the above data and trends into consideration, we conclude that DSPs, at a minimum, need to receive equal compensation to Nursing Assistants as they provide a similar level of care. In addition, this would level the playing field since providers of intellectual disability and autism supports/services and providers of nursing home services are competing for the same candidates for potential employees.

When taking into consideration the reality that a large portion of the 34,000 DSP workers in our study work overtime or rely upon public subsidies to make ends meet, a fair wage for a DSP should be at least $18 per hour, which would increase their projected annual earnings from $24,752 to $37,440. A DSP wage of $18 per hour still falls below the living wage recommendations,1 but it would improve service quality by reducing turnover rates, decreasing vacancy rates, and reducing current overtime practices which result in overworked DSPs, and reducing reliance on public assistance.

1 According to a study from the Alliance for a Just Society, a living wage for a single adult in Pennsylvania would be $16.41 per hour. A single adult with a school-age child should make $24.35 per hour, with two children, that increases to $31.67 per hour.

PUBLIC BENEFIT ENTITLEMENTS TO SUPPLEMENT DSP SALARIES

Nationally, low wages cost taxpayers $152.8 Billion annually in costs related to supporting working families with public benefits, per a 2015 studyxvi from the UC Berkeley Labor Center. The study states:

“Stagnating wages and decreased benefits are a problem not only for low-‐wage workers who increasingly cannot make ends meet, but also for the federal government as well as the 50 state governments that finance the public assistance programs many of these workers and their families turn to. Nearly three-‐quarters (73 percent) of enrollees in America’s major public support programs are members of working families; the taxpayers bear a significant portion of the hidden costs of low-‐wage work in America.”

Working families with young children, especially single parent families, are more likely to receive multiple public benefits. This family type is more likely to be low-‐income. Because of this, many public subsidy programs target outreach to help them secure benefits. Public support helps many single parent families meet basic needs.xvii However, navigating eligibility requirements can be difficult. The process is likened to that of a Rubix Cube, wherein the various pieces of the puzzle are difficult to line up. Income eligibility levels differ for each type of public support, programs count different forms of income to determine eligibility, while still other programs allow recipients to deduct basic needs from their income creating further ambiguity.

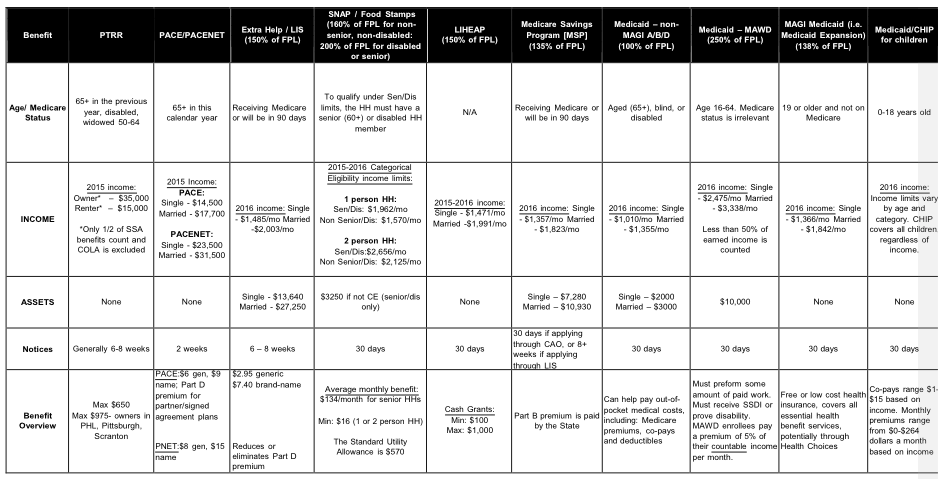

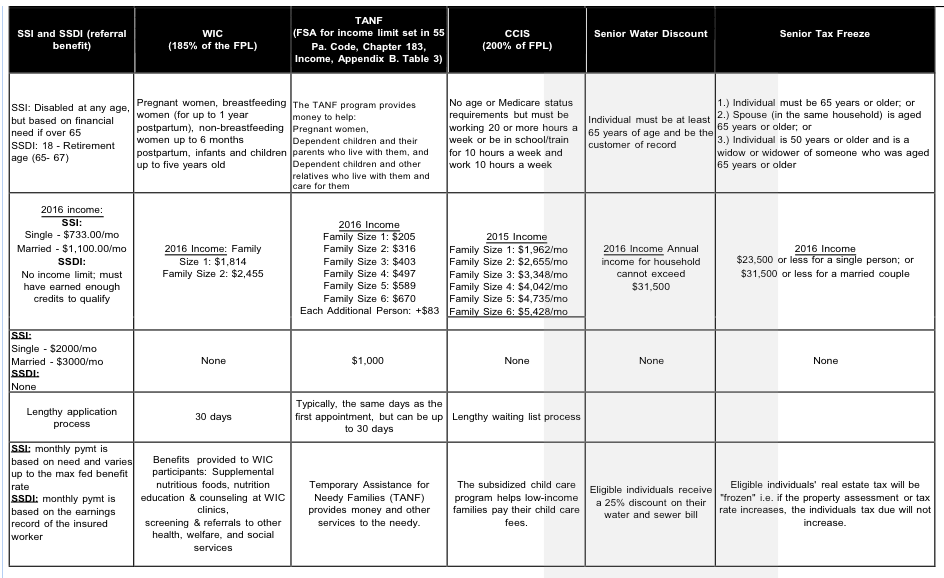

Organizations such as Benefits Data Trust have developed sophisticated algorithms and computer programs to navigate the public benefits maze. Benefits Data Trust has developed a chart (Appendix B) that serves as a guideline rubric for benefit qualifications. The chart summarizes 16 benefit programs for which an individual would qualify based on age, income, assets, and family size. Benefit qualifications, payouts, and scheduled disbursements differ in each of these benefit programs, and the size of the benefit payout differs for each benefit based on the requisite qualifications listed. Other organizations such as Single Stop USA and Benefits Kitchen have also developed software to align individual scenarios to public benefit qualifications. The complexity of obtaining these benefits is an obvious deterrent for the persons and families who might potentially benefit from these programs, such as the average low-‐wage DSP worker.

To provide perspectivexviii, based on the national average, an individual working 40 hours per week and making below $12.16 an hour (or $25,293 annually) would qualify for an average of $1,917 in Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC); $1,078 in Child Tax Credit (CTC); $295 in Low-‐Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP); $3,162 in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); $3,308 in Housing Assistance, $2,201 in Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF); and $712 in Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). If all benefits were obtained, the average DSP would qualify for $12,673 in public benefits, excluding Medicaid.

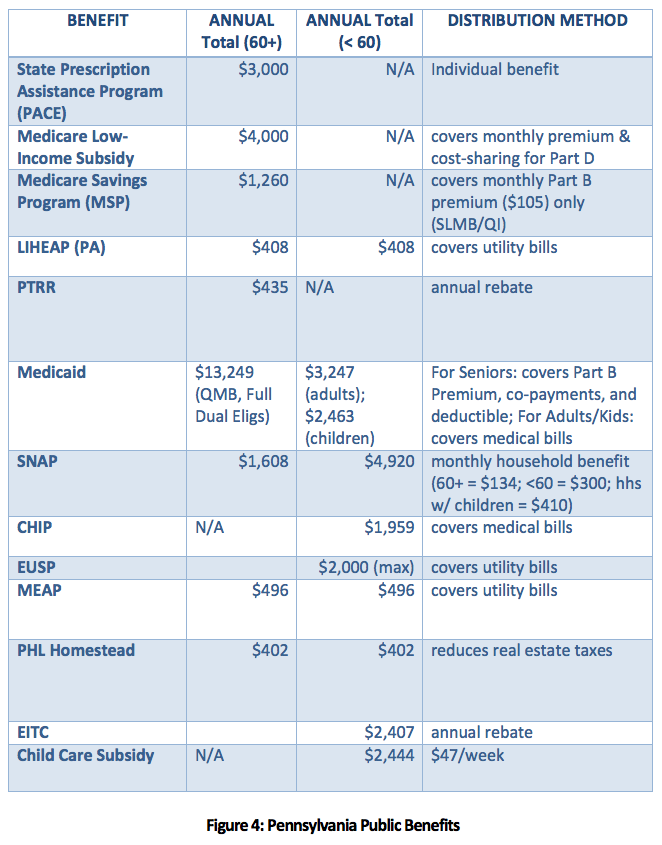

The below figure provided by Benefits Data Trust references benefits payouts and qualifications specific for Pennsylvania.

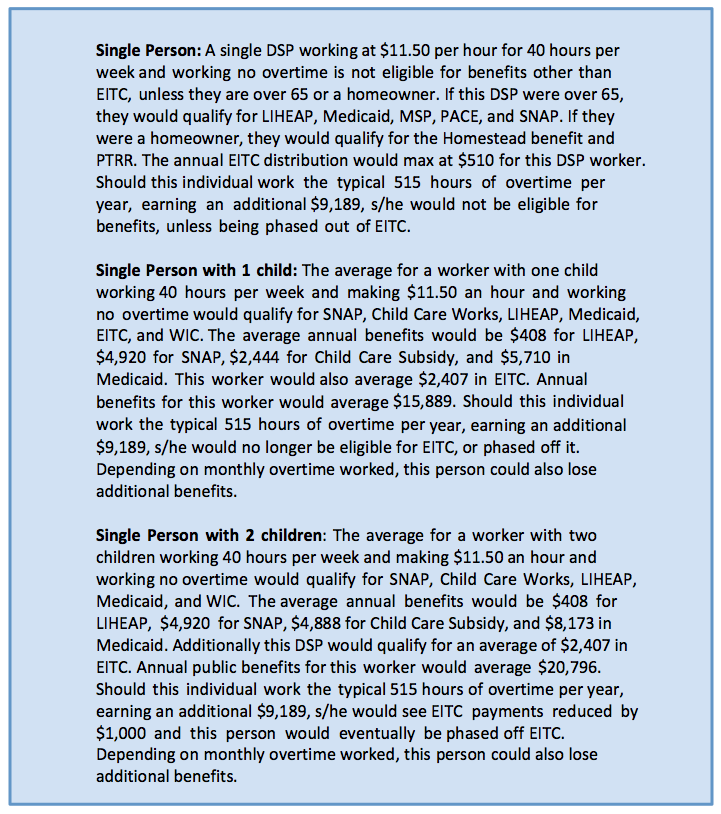

To better understand how wages are correlated with public benefits, below are three scenarios of a DSP worker in PA earning $11.50 per hour; a single DSP worker in PA with one dependent earning $11.50 per hour; and a single DSP worker in PA with two dependents earning $11.50 per hour.

Our reliance on illustrative scenarios is the unfortunate product of the complexities of public benefits qualifications and data that does not exist (i.e. valid estimates of the family compositions of the Pennsylvania DSP workforce and numbers of DSPs who receive public benefits by type). The savings on public benefits requires additional data on Pennsylvania DSPs’ access to benefits. Rather than offer an estimate of likely benefits based on guesswork, a scenario based approached was adopted. Admittedly, this is less than ideal, but it emerged as the only reasonable compromise.

WHAT IS THE CORRELATION BETWEEN INCREASED WAGES AND PUBLIC BENEFIT SUBSIDIES?

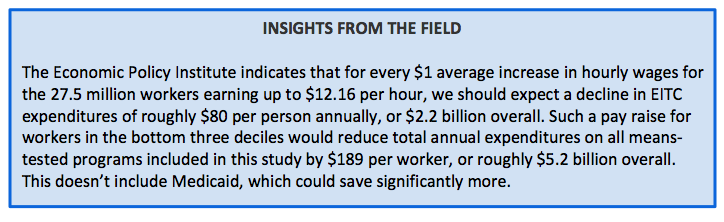

Based upon the 2016 study from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI),xvii raising wages for all workers making below $12.16 an hour will reduce taxpayer spending on public benefits. Raising wages to $18 per hour does not guarantee that all public benefits will be eliminated. However, it does move many DSPs along the continuum to being self-sufficient and not needing public subsidies. In addition, it saves taxpayer dollars. The Economic Policy Institute demonstrated that for every one dollar increase in hourly wages for the roughly 27.5 million workers earning up to $12.16 an hour, the share relying on public assistance is predicted to decline by 3.1 percent.

What is important in the Pennsylvania context is that many DSPs in Pennsylvania currently work overtime due to low wages and depend upon this additional income to meet basic living requirements. For many of these DSPs, by working overtime hours, they eliminate their eligibility for public benefit subsidies. This requires most DSPs to make an unfortunate trade-off: either accept public benefits, or work significant overtime to make ends meet.

WHAT HAPPENS IF DSP WAGES ARE INCREASED TO $18 PER HOUR?

Impact on Consumers: High turnover negatively impacts the quality of service delivery. Employees are the most critical input to achieving high-performance outcomes.xx Reducing turnover translates into increased program continuity and an enhanced ability to provide ongoing support to each individual consumer. With a significantly higher pay rate, providers would attract more capable staff that would provide consumers with a higher quality of care. It would reduce competition with other businesses like fast food chains for employees with the most potential. Providers would become an employer of choice, much as the state developmental centers have been employers of choice for years.

Impact on DSP Employees and their families: Referencing Pennsylvania dataxxi the typical DSP at $18 per hour would now earn $37,440 annually, and even with reducing overtime by 60 percent to 206 hours for a DSP each year, many DSPs could still earn an additional $5,572 per year ($43,012 total per year). In all likelihood, DSPs would lose access to and not need most forms of public benefits with an increase in their hourly wages. They would be able to work fewer hours and be more financially capable of supporting their children in achieving educational goals.

The literature has documented that an individual that had to either work overtime or subsist on public benefits due to low wages has been proven to experience diminished health, increased obesity, and hypertension.xxv This low-wage environment has a striking human cost. It minimizes the ability of parents to fully participate in their children’s development, and children of low-wage parents are often forced into the labor market early. Children of low-wage parents are more likely to face educational difficulties, and “trade-offs between spending time with children and earning an adequate wage can trap parents in familial hardship.” Finally, children of low-wage earning parents are more at risk for health problems and complications.xxvi

Impact on Tax Payers: The literature suggests that vacancies and overtime are surprisingly linked to wages. Low wages, even within the context of the relatively narrow range of hourly wages, correlate to higher rates of vacancy and turnover. A reasonable hypothesis would be that higher pay might reduce turnover. We note that higher pay to employees of state centers has been associated with positive outcomes such as lower rates of turnover (Price, 2015), with Ohio Civil Service Employee Association president Christopher Mabe reporting state center turnover rates as low as 10 percent. A similar news report (Hult, 2017) cited a reduction in staff turnover in a mental hospital following a pay increase.

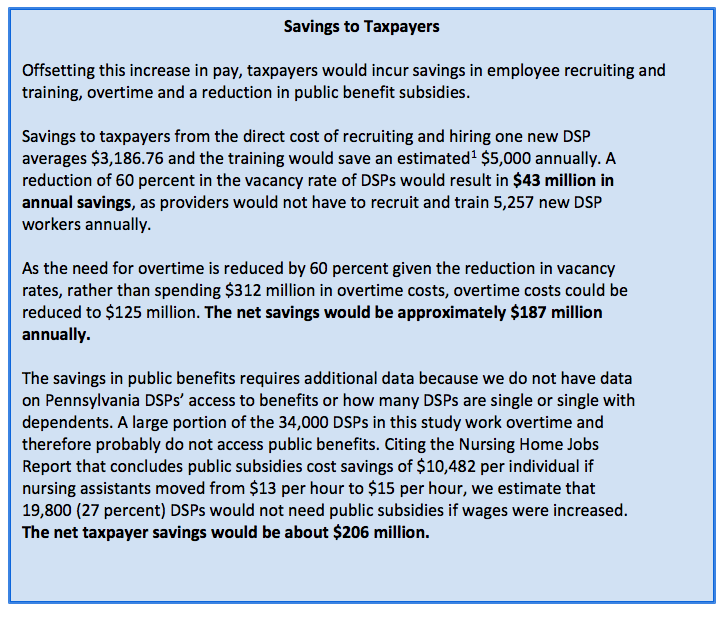

A reasonable question then becomes to what extent turnover and vacancies might decline in the event of an increase in DSP compensation in Pennsylvania. Once again, strong data on this issue is unavailable. The Hult study mentioned the above referenced 60 percent decrease in turnover in a state mental hospital. We have elected to follow the Hult study conclusion of a 60 percent decrease in turnover if wages increase to $18 per hour. Given this conclusion, below are the costs and benefits to taxpayers.

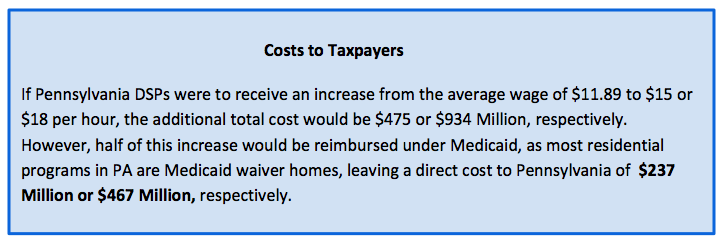

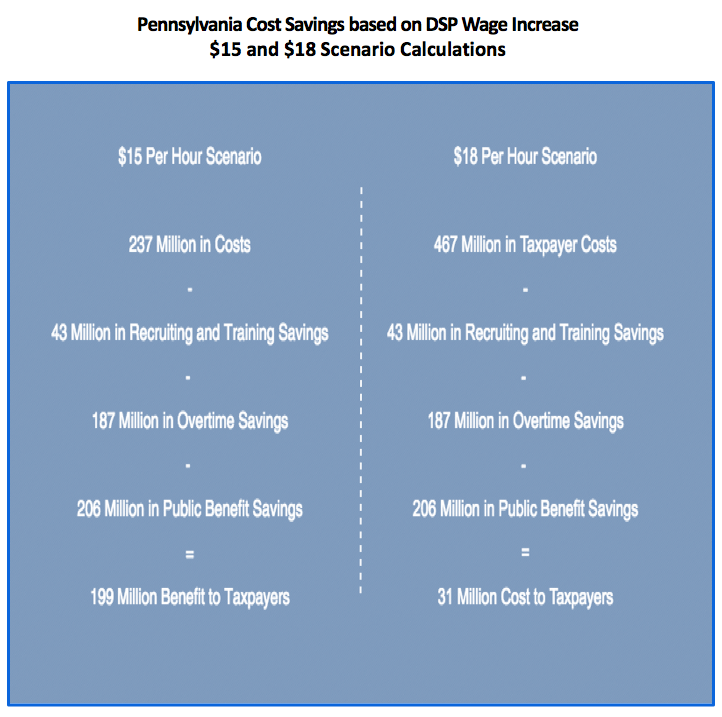

Considering the two scenarios of raising DSP wages to $15 and $18 per hour respectively, increasing DSP wages to $15 per hour would cost taxpayers $237 million ($7,275,000 would be returned in income tax payments), but would ultimately result in taxpayer savings of $199 million. Increasing wages to $18 per hour would initially cost taxpayers $467 million annually which would be reduced to $41 million once taxpayer savings were accounted for. This equation does not consider the $934 million that would be injected into the Pennsylvania economy in the form of higher wages for workers resulting in additional state and local tax revenues.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

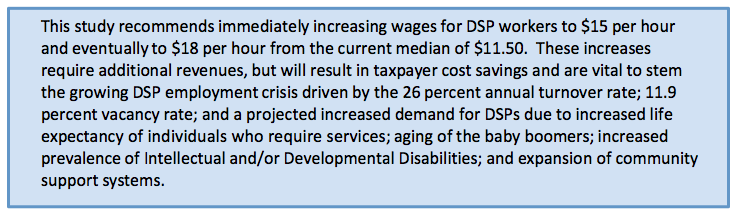

- Immediately increase wages for DSP workers to $15 per hour and eventually to $18 per hour from the current median of $11.50. These increases initially require additional funding, but will result in long-term and substantial taxpayer cost savings and are vital to avoid the growing DSP employment crisis driven by the 26 percent annual turnover rate; 11.9 percent vacancy rate; and a projected increased demand for DSPs due to increased life expectancy of individuals requiring services; aging of the baby boomers; increased prevalence of intellectual and/or developmental disabilities and behavioral health concerns; and expansion of community support systems.

- Fund a pilot study for one to two percent of the DSP population (an estimated 736 – 1,472 individuals) that will determine the benefits of increasing the DSP base hourly wage of $18 per hour for each directly employed or subcontracted employee of an agency hiring DSPs.

CONCLUSION

Pennsylvania public officials, in order to address the DSP workforce crisis (26 percent turnover rate; a 11.9 percent vacancy rate; and a projected increased demand for DSPs) and substandard care for Pennsylvania’s most vulnerable, need to enact a transparent rate setting process that will provide adequate wages for DSPs that eliminate the need for public assistance and will provide them with the dignity they deserve. We recommend an immediate increase in wages for DSP workers to $15 per hour with a scheduled increase to $18 per hour from the current median hourly wage of $11.50.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special Thanks to Benefits Data Trust who provided the public benefits chart and the benefit access scenarios. Benefits Data Trust assists tens of thousands of people with government programs using private sector strategies.

AUTHORS

Michael Clark, M.P.A., is the Executive Director of Impact Germantown. He is a systems entrepreneur based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He has researched, published, and worked in the areas of collective impact, financial innovation, impact investing and social entrepreneurship. Mike is the lead researcher and policy analyst regarding the social impacts of paying direct service workers low wages forcing them to be dependents upon society through public benefits and reducing the quality of care due to high staff attrition and increased stress levels. Mike also served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Bulgaria. He holds a Bachelor’s degree from the University of Scranton, and a Master of Public Administration from the University of Pennsylvania’s Fels Institute of Government.

Scott Spreat, Ed.D. is the President of Woods Research and Evaulation Institute at Woods Services. He has been a member of the Woods team since joining in 1992 as the Administrator of Clinical Services. He was responsible for designing, opening and running the Woodlands program and served as its Executive Director before being promoted to Vice President for Behavioral Health in 2005. In recent years, Dr. Spreat has been the key liaison with Harrisburg legislators and lobbyists and serves on the board of PAR (Pennsylvania Advocacy and Resources for Autism and Intellectual Disability). He was a member of the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disability’s Terminology and Classification Task Force and served in the work group that developed the definition of Intellectual Disability. Dr. Spreat received his doctorate in Educational Psychology and is a licensed psychologist who worked for Temple University’s Woodhaven Center, conducting research, directing the clinical services department, and serving as the Executive Director of the 284-bed program before coming to Woods.

Nicholas D. Torres M.Ed. has over 20 years of experience in executive management. He built and led one of the largest and nationally recognized human services organizations; founded/governed/led two charter schools and a nonprofit dedicated in scaling high-impact social enterprises (e.g., school based health centers; college access and completion pipelines; and early literacy technology platform); founded and currently leads a social sector “think-tank” organization; and teaches at UPENN Fels Institute of Policy and the Wharton School. From 2000 – 2010 Nicholas served as President of Congreso de Latinos Unidos. Under his leadership, Congreso was one of just six national leadership investments ($5 million) from Edna McConnell Clark Foundation to demonstrate multi-service organization impact on young people aged 16-24. As a result of this investment, he created a first-of-its-kind performance management system to measure organizational effectiveness for over 50 service lines and 17,000 clients/customers that would later be used as a model for Social Solutions’ Efforts To Outcome (ETO) to scale in nonprofits nationally. He then served as a member of the National Alliance for Effective Social Investments that led the nation on integrating Social Impact Indicators into nonprofit best practices. Currently, Mr. Torres serves as CEO/Co-Founder of Social Innovations Partners that manages the Social Innovation Journal; Institute; and Lab and teaches Policy; Leading Non Profits; and Social Enterprise at the University of Pennsylvania. He has co-authored several books and serves on many regional and national. Mr. Torres received his BA from Carleton College and his Master's in Educational Psychology from the University of Texas at Austin.

APPENDIX A: HOUSE BILL 1449 AND SENATE BILL 1057

Pennsylvania Bill: Nursing Home Accountability Act (House Bill 1449[7] (Rep. Ed Gainey) and Senate Bill 1057[8] (Sen. Daylin Leach)

“Nursing facilities are predominately taxpayer-funded through reimbursements from the medical assistance program and Medicare program”[9] and that “Taxpayers should not subsidize nursing facilities to reap profits while many of their employees are living in poverty.”[10]

The Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry reports, “the average wage for nurse assistants is $13.39 and the average wage for dietary and housekeeping employees is $9.81.”[11] PathWays PA, a not-for profit Pennsylvania organization that provides services and advocacy for women, children, and families,[12] finds, “a wage of $15 per hour would meet the sufficiency standard for many, but not all, counties of this Commonwealth for an employee with one child to provide for the employee and child without the need for public assistance.”[13]

The Bill also states, “A worker who faces low wages or part-time work, or both, is too often eligible for taxpayer-funded medical assistance instead of affordable, employer-based coverage. Controlling health care costs can be more readily achieved if a greater share of working people and their families have health benefits so that cost shifting is minimized.”[14]

Accordingly, the proposed Nursing Home Accountability Act has four purposes:

(1) Create a living wage certification program for each nursing facility that provides a base hourly wage of $15 per hour for each directly employed or subcontracted employee of the nursing facility.

(2) Encourage the provision of a living wage to each nursing facility employee by providing information to each nursing facility resident and the public on the wage rate paid to the employees of the nursing facility.

(3) Ensure that each nursing facility pay a nursing facility employer responsibility penalty for health coverage received by each employee of the nursing facility through the medical assistance program and another public assistance program that is fully or partially funded with funds from the Commonwealth, with that penalty based on the costs incurred by the Commonwealth for providing these benefits to the employee of the nursing facility.

(4) Ensure that each nursing facility employee who receives public assistance is protected from possible retaliation by the nursing facility for seeking or obtaining that assistance.[15]

There are two key components of the legislation:

A Nursing Facility Living Wage Certification program “requires each facility participating in the Medicaid program to report” information,[16] in a verifiable and auditable form,[17] about the minimum base hourly wage paid for each job classification and the number of employees in each classification. The Department of Public Health will give a “living wage certification” to each facility whose wages meet the living wage certification standard,[18] which is defined as $15 as a base hourly wage, adjusted annually.[19]

A Nursing Facility Employer Responsibility Penalty imposes a penalty on each facility whose employees are receiving public assistance, with the amount of the penalty based on the “actual cost of providing public assistance to each covered employee for the most recent fiscal year.”[20] The Bill authorizes limited administrative appeals: facilities may “only challenge whether the Department correctly determined the number of covered employees that are the subject of the penalty.”[21] The Department of Human Services may deduct any unpaid penalty and interest from Medicaid payments that are otherwise due the facility[22] and the Department of Health may refuse to renew the license of a facility that has not paid the penalties and interest or agreed with the Department on a plan of installment payments.[23] The Bill provides for interest payments;[24] prohibits practices that designate employees as independent contractors, prohibit employees from enrolling in public assistance, or discriminate against employees enrolled in public assistance;[25] and provides for employee remedies.[26]

APPENDIX B: PUBLIC BENEFITS CHART

References

i Hewitt, A., & Larson, S. (2007). The direct support workforce in community supports to individuals with developmental disabilities: Issues, implications, and promising practices. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13, 178-187.

ii Hewitt, A., & Larson, S. (2007). The direct support workforce in community supports to individuals with developmental disabilities: Issues, implications, and promising practices. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13, 178-187.

iii US Department of Health & Human Services. (2006). The supply of direct support professionals serving individuals with intellectual disabilities and other developmental disabilities: Report to Congress. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

iv Larson, S., Hewitt, A., & Knoblauch, B. (2005). Recruitment, Retention, and Training Challenges in Community Homes: a review of the literature. ‘In S. Larson & A. Hewitt (Eds.), Staff recruitment, retention, & training strategies for community human services organizations (pp1-18). Baltimore: Brookes.

v Bogenschutz, M., Hewitt, A., Nord, D., & Hepperlen, R. (2014). Direct support workforce supporting individuals with IDD: Current wages, benefits, and stability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 52(5), 317-329.

vi Sidman, M. (1960) Tactics of Scientific Research. New York City: Basic Books.

vii Spreat, S., Brown-McHale, K., & Walker, S. (2016). PAR Pennsylvania DSP Wage Study. Lemoyne, PA: PAR.

viii Spreat, S. (2017). Pennsylvania Direct Support Professional Wage Study. Langhorne, PA: Alliance of Community Service Providers (ACSP), Moving Agencies toward Excellence (MAX), Pennsylvania Advocacy and Resources for Autism and Intellectual Disability (PAR), Rehabilitation and Community Providers Association (RCPA), Arc of Pennsylvania (Arc/PA), The Provider Alliance (TPA), United Cerebral Palsy of Pennsylvania (UCPA).

ix Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2016. Link.

x Link.

xi Spreat, S. (2017). Pennsylvania Direct Support Professional Wage Study. Langhorne, PA: Alliance of Community Service Providers (ACSP), Moving Agencies toward Excellence (MAX), Pennsylvania Advocacy and Resources for Autism and Intellectual Disability (PAR), Rehabilitation and Community Providers Association (RCPA), Arc of Pennsylvania (Arc/PA), The Provider Alliance (TPA), United Cerebral Palsy of Pennsylvania (UCPA).

xii Test, D., Flowers, C., Hewitt, A., Solow, J., & Taylor, S. (2003). Statewide study of the direct support staff workforce. Mental Retardation, 41(4), 276-285.

xii Olds, D. & Clarke, S. (2010). The Effect of Work Hours on Adverse Events and Errors in Health Care Access. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PCD2910393.

xiii Herzenberg, S. (2015). Nursing Home Jobs That Pay. Keystone Research Center

xiv Kasperkevic, J. (2014). The benefits cliff: When minimum wage increase backfires on the people in need. Link.

xv Albeida, R. * Carr, M. (2016). Between a rock and a hard place: A closer look at cliff effects in Massachusetts. UMASS Boston Center for Social Policy. Link.

xvi Jacobs, K., Perry, I., & MacGillvary, J. (2015). The High Public Cost of Low Wages. Poverty Level Wages Cost US Taxpayers $125.8 Billion Each Year in Public Support for Working Families. UC Berkeley labor Center. Link.

xvii Albeida, R. * Carr, M. (2016). Between a rock and a hard place: A closer look at cliff effects in Massachusetts. UMASS Boston Center for Social Policy. Link.

xviii Cooper, D. (2016). Balancing paychecks and public assistance. How higher wages would strengthen what government can do. Economic Policy Institute. Link

xix Seldan, S. (2015). Voluntary turnover in nonprofit organizations: The impact of high performance work practices. Human Services Organization Journal. Link

xx Spreat, S. (2017). Pennsylvania Direct Support Professional Wage Study. Langhorne, PA: Alliance of Community Service Providers (ACSP), Moving Agencies toward Excellence (MAX), Pennsylvania Advocacy and Resources for Autism and Intellectual Disability (PAR), Rehabilitation and Community Providers Association (RCPA), Arc of Pennsylvania (Arc/PA), The Provider Alliance (TPA), United Cerebral Palsy of Pennsylvania (UCPA).

xxi Leigh, P. (2013). Raising the minimum wage could improve public health. Economic Policy Institute. Link