Introduction

Henry Miller, in his beekeeper suit, walked nervously through the doors and into the tank. The five sharks looked up, warmly smiling at him while he made his pitch. As soon as Henry stopped speaking, however, the sharks began to stir and the previous warmness changed to coldhearted critique. Miller’s company, which represented years of hard work and $150,000 of his parents’ money, depended on his success in selling his flavored honey idea. Kevin O’Leary began to circle: “I believe the big guys will crush you like the bug you are; I’m out.” Two more sharks expressed concern for the future of the business and followed Kevin out of the deal, thus leaving only two more chances to win someone over and save the company…

On March 15, 2014, ABC’s “Shark Tank” aired its children-themed episode. In this episode, two of the entrepreneurs made deals with the sharks, including Henry’s Humdingers, a flavored honey business that took a 75% combined equity offer from Mark Cuban and Robert Herjavec. The airing of the episode was itself a risk because many of the “Sharks” have faced criticism that they take advantage of entrepreneurs, who in this case were children; the youngest entrepreneur for this episode was a six-year-old girl.

The experience and opportunity from diving into the tank with the sharks, however, is unparalleled. The program has been described as venture capital on steroids. Furthermore, the “Shark Tank” program, since it began airing in August 2009, has brought with it many intangible benefits and has served to inspire many to create and innovate across the age spectrum. The program encourages innovation, despite America being in the grips of the worst economic conditions since the Great Depression. It has helped reignite America’s entrepreneurial spirit and change the attitude of many to believe that they can build something of their own. The American Dream is very much embodied in the spirit of the show.

Today, the economy finds itself in perhaps a better state than since before the most recent recession; however, for much of the young adult population, the situation still looks bleak. Four out of ten graduates are in underemployed professions that do not require a bachelor’s degree. Many students who have completed their bachelor’s degrees have also built up a lot of student debt over their years in college. For those without a college degree, the situation is worse (Lee 2014). Attaining a degree is not necessarily a solution to finding future prosperity, and many factors are making life more difficult for new graduates.

There is also a worry that the gap between education and the real world is widening. The classical disciplines may not be as applicable as they were in decades past. Many share the belief that our education system should be directed toward skill sets such as those required to seal the deal on “Shark Tank” and that our education should be a platform to add value to the real world. The emphasis should instead be on empowering students to think for themselves and learn practical skills. This is certainly the viewpoint of Schoolyard Ventures, formerly Startup Corps, as will be further exemplified in this article through its mission and the experience of its founders as it seeks to continue to innovatively improve education in Philadelphia and across the nation.

Background on Philadelphia’s Economy and Education

Philadelphia’s degree attainment rate currently ranks 6th among the ten largest metropolitan areas in the United States. In greater Philadelphia, over 33% of adults have a bachelor’s degree or higher (World Class Greater Philadelphia 2014). In K-12 education, Philadelphia also performs well: 83% of greater Philadelphia’s students graduate on time, compared with the national average of 80%, but there is as much variation in results across counties as there is in personal income.

In the last decade, the nature of K-12 education in Philadelphia has changed. There has been a steady decline in enrollment in Catholic and public schools and a steady increase in enrollment in charter schools, with much public funding following students to these schools (Pew Charitable Trusts 2013). In the last few years, there has been a lot of attention given to Philadelphia schools and the financial state of the school district. This is a problem that is set to re-occur until the city, state and school district agree on a plan of action to repair the situation.

Conversely, Philadelphia has continued to feel the effects of recession greater than the rest of the nation. It is consistently compared with some of the poorest cities in the country. In 2011, Philadelphia, among some of the larger cities in the nation, had the third highest poverty rate (28.4%) behind Cleveland and Detroit. Philadelphia performs considerably poorly in comparison with the national rate of 15.9%. Median household income also comes in low at $34,207 compared with the national median household income of $50,502. The city’s unemployment rates have also consistently been worse than those in the rest of the country, with Philadelphia’s 2012 unemployment rate at 10.7% compared with the national rate of 8.1%. The city’s recovery has been slow since the recession, and the unemployment rate was higher in 2012 than it was in the 2009 recession year (Pew Charitable Trusts 2013).

Philadelphia also has a reputation as one of the most unfriendly cities for businesses in the country. Former City Councilman Bill Green himself described the city as a “business-unfriendly culture.” Much of the criticism has been concentrated on the city’s tax structure, particularly the double burden of both the business income and receipts tax and the sales tax. In addition, much of the city’s tax revenue also comes from the wage tax, which discourages potential employees from working in the city. The nature of the regulatory structure has also added to this poor reputation. “The biggest hurdle is our business-unfriendly reputation caused primarily by our punitive business tax structure, followed closely by our unfriendly business-regulatory structure,” said Stephen Mullin from Econsult (Econsult Solutions 2013).

Measures have been put in place to attempt to address the city’s problems. Last year, Mayor Nutter signed a bill to form the Jump Start Philly program, which gives new businesses in Philadelphia a two-year exemption from paying the business income and receipts tax as well as exemption from paying certain license fees (Drucker and Scaccetti 2014).

Some of Mayor Nutter’s measures may have seen some fruition: there is a burgeoning startup scene in Philadelphia. Parts of Old City and Northern Liberties have become hubs for innovative startups in an area that has been dubbed N3rd Street (Chepurny 2012). Data confirm this growth. A report published by the Economy League illustrates that Philadelphia enjoyed a 42% increase in venture capital deals from 2009 to 2013 (Reyes 2014).

Philadelphia has great startup potential, with many higher education institutions from which to leverage talent and expertise, including: University of Pennsylvania, Drexel University, Temple University, Villanova University, Haverford College and many other higher education institutions. As mentioned previously, Philadelphia has a strong level of higher education attainment and a young population, which serves as a great potential labor resource. In addition, Philadelphia’s proximity to some of the biggest metro economies in the world is a great stage for spreading the networks of new businesses; however, the number of new business establishments in Philadelphia has still not fully recovered from the recession.

While it did not experience the volatility reflected in the national figures, Philadelphia has been slower to bounce back, with the number of establishments still down over 3% compared with 2.2% nationally from 2008 to 2012 (United States Census Bureau, n.d.). While the recovery has been painful and slow for Americans and Philadelphians, the situation continues to improve, and there is a buzz of excitement over the possibilities that startups offer.

Background on Schoolyard Ventures

When understanding the perspective and driving forces behind Schoolyard Ventures, one only has to look at its founding members to understand the underlying passion. Rich Sedmak grew up in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, just outside of Philadelphia, where he attended public school. He often got in trouble as a child for not paying attention in the traditional classroom setting. His outlook changed when he started a computer repair business in high school. He grew the company to six employees and quickly found out that he was learning at a much faster pace with his business than he was in the classroom. After high school, Rich went on to start a number of other businesses, including a software analytic firm that was eventually bought out by a larger firm.

After selling his firm, Rich wanted to take his learning experience from the businesses he had started and run and use that knowledge to empower children by teaching them similar skills. He saw that many schools wanted to have entrepreneurship programs, but did not have the ability to pull them off. So Rich, along with friends—and serial entrepreneurs—Christian Kunkel and Richard Binswanger, started Startup Corps in 2007.

Christian Kunkel’s background is multifaceted and includes working for Corporate University Exchange, which provides research and consulting on corporate training, corporate university design and leadership development to multinational corporations. Currently he is also the CEO of Slate, which aims to improve access to education technology by providing an open-source infrastructure that integrates all of a school’s software tools.

Richard Binswanger has a lot of experience in Philadelphia nonprofits. Apart from his tenure with Startup Corps and Schoolyard Ventures, he also chairs the board of the National Foundation for Celiac Awareness in Philadelphia and the advisory board of the Philadelphia Mural Arts Council. In addition, Binswanger has had years of experience working in and leading technology startups.

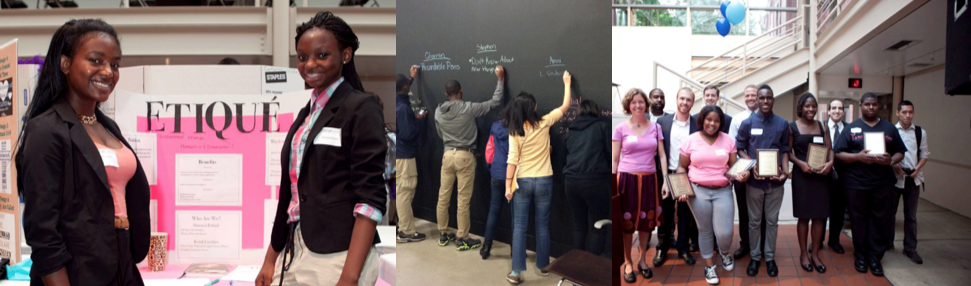

Startup Corps was a 501(c)3 whose mission was “to provide curriculum, workshops, mentorship, and micro-capital for high school students in Philadelphia who wish to launch micro-ventures” (http://startupcorps.org/startup-corps-mission/). Startup Corps encouraged learning through the program at each individual’s own pace, allowing students to experiment with their various business ideas. Instructors and mentors help students through this process. The students work through each unit toward the goal of the milestone events. One such event is the Shark Tank-style pitch competition in which students pitch their ideas to a panel of experienced business leaders. The other is the Youth Entrepreneurship Expo, where students demonstrate their ventures, sell their products and speak with experts, investors and the media.

Startup Corps finished the 2014 school year having served 124 children with five full-time employees and sixty student mentors. Many of the children came to Startup Corps through Philadelphia’s Department of Human Resources. The City of Philadelphia has also provided additional support other than pools for talent. The City, through the Department of Commerce and Industrial Development Corporation, awarded Startup Corps a StartUp PHL grant to support the city’s commitment to strengthening the entrepreneurial environment in Philadelphia by backing smart proposals.

Schoolyard Ventures is supported by a strong group of mentors and partners. The mentors for the program are entrepreneurs from Philadelphia whose experience ranges from a variety of industries. They are hands-on with the students in helping them launch their businesses. For example, mentors play a vital role in assisting the students to put together their presentations for the pitch competition. Some of the Startup Corps partners who aided the program with financial support and mentorship included: Internet Capital Group, RAF Industries, Kiva Zip (which included some of the participating teens as borrowers from their program) and the Mural Arts Program.

Many success stories have come through Startup Corps. Sharif Tarver, from Charter High School for Architecture and Design, founded and still manages a nonprofit called Philly’s Future Talent, a performing arts talent agency. While he is currently enrolled at Green Mountain College, he also has six staff members with whom he is in daily communication. His startup had a number of artists perform at Jay-Z’s Made in America concert after he was able to cut a deal with the publicly-listed Live Nation Entertainment.

David Zamarin, from the Philadelphia school district’s Masterman School, founded DetraPel, a water- and stain-repellent product for items such as shoes and handbags. Prior to that, he founded a shoe cleaning business, which he sold. David has been very successful with his product, with over $25,000 in sales, and his sales are continuing to grow.

For the 2012–2013 academic year, Startup Corps had significant impacts on those who participated in the program.

- Of the 126 students for that year, 95% of them took their products to market

- 86% had generated revenue through their ventures

- $15,000 of micro-capital was provided to students through loans or grants

- 57% of students came from low-income backgrounds

While Rich is proud of the work accomplished at Startup Corps, he felt that a transition was needed to take the organization to the next level. He retained all of his current employees and mentors, but is rebooting nonprofit Startup Corps as the for-profit Schoolyard Ventures.

Schoolyard Ventures takes the Startup Corps idea further, believing that “education should be a platform to add value to the real world” (R. Sedmak, personal communication, July 2014). Rich plans to have a platform for revenue generation for Schoolyard’s services to expand upon those already offered and create a replicable licensed curriculum for schools across the country. When schools pay for the licensed product, they then have buy-in responsibility. Schoolyard will continue to offer 0% interest micro-loans for students, but on an online platform they are developing called TeenFund. Students in the new program can also have “Schoolyard Venture Cards,” which will be debit cards for children so that teachers do not have to be responsible for the day-to-day cash activities required to run the business.

The initial cost for the revenue-generating platform will be $5,000 for twenty-five participating children per school. This cost includes teachers, mentors and a customized curriculum. Currently, four schools will be participating in the fall pilot program, with twenty schools on the waiting list that Schoolyard Ventures hopes to include in the program by the spring. The founders of Schoolyard Ventures are taking a cautious approach with their new platform by rolling out the service to twenty of the 152 combined total of charter schools, district high schools and Catholic high schools in the city (Archdiocese of Philadelphia, n.d.; School District of Philadelphia, n.d.). The makeup of students will be 75% from public schools and 25% from private schools. Of these, half of the students will be from within the City of Philadelphia and the other half of the students will be from the Philadelphia suburbs. All employees, mentors and students who were part of the program when it was Startup Corps will be transitioned over to Schoolyard Ventures.

Schoolyard Ventures aims to launch a residential gap year program for students who are leaving high school. Before its rollout, Schoolyard intends to use the time to recruit students and build a yearlong curriculum. The program aims to have students come from all over the country and start businesses in Philadelphia. The funding for this part of the program is to come from the tuition students will pay. The actual tuition amount will be determined at a later date.

When asked about how he viewed the long-term vision for the growth of Schoolyard Ventures, Rich responded that he wanted to widen options for students who were exiting high school and reform the learning models of the last fifteen years. He expressed concerns about the limited options young people have when they leave high school including their collective lack of real-world experiences after graduating. He alluded to the example of the allocation of federal government funds toward workforce development. Much of the billions of dollars spent only teaches skills to create more short-order cooks and does not empower people with critical skills and experiences. Rich desires to continue to inspire people with entrepreneurial spirit that makes them want to shape their own destiny. Ultimately, he sees the traditionally accepted, and overemphasized, credentials that are offered by schools as on their way out. He “wants to accelerate that fall” through the work of his organization (R. Sedmak, personal communication, July 2014).

An example of another organization that has had success in this space is the Workshop School in Philadelphia, which shares the goal of moving away from simply attaining credentials and focuses on empowering children with real-world skills. Similarly, Workshop believes in developing real experience and problem-solving skills, which is at the center of its curriculum. The school has had very successful outcomes, with 100% of the seniors graduating on time and 90% accepted into a college or university (http://www.workshopschool.org/about-the-workshop/background/). This is in comparison with the 65.9% of high school graduates who are enrolled in colleges or universities, proving that a dynamic education model can have positive outcomes (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014).

Through the Schoolyard Ventures program, Rich wishes to increase high school graduates’ options. The cost of higher education in the U.S. has risen faster than Americans’ ability to pay it, and this has taken higher education out of reach for many low-income families. A student’s ability to go to college then depends on his or her ability to find scholarships, loans or financial aid to assist them. In addition, between employers’ continued reliance on typical credentials and the income differences between college and high school graduates, a cycle is created in which low-income individuals cannot make vertical movement. Schoolyard aims to break this cycle and empower students to innovate.

The Schoolyard Ventures idea is not entirely new, and many organizations across the country have different models for achieving similar goals. The LightHouse Entrepreneurial Accelerator Program (LEAP) in Ohio offers a summer program for high school entrepreneurs during which mentors and experts from participating communities work directly with the program’s students (LightHouse Ohio 2013). Get aHead for Business is an entrepreneurial business curriculum for high school students that combines interactive classroom learning with real-life experience. Backed by the Young Americans Center for Financial Education, the program, similar to Schoolyard, has a business competition for students to test their ideas while they’re participating in the program. This organization has created a close relationship with schools in the region, and students can attain academic credit for either high school or community college. The program has gained much traction in Colorado and has received funding from the KeyBank Foundation to help fund student-run businesses. In addition, due to the KeyBank partnership, the curriculum for the program is free for teachers (Get aHead for Business). While there are many similar organizations, Schoolyard Ventures offers multiple dimensions as part of its whole program package. The combination of hands-on mentorship, a tested curriculum, funding opportunities and experiment-based learning makes Schoolyard a unique program in a league of its own.

If Schoolyard Ventures is successful, it will potentially encounter opposition in the form of traditionally recognized college and university credentials such as associate’s and bachelor’s degrees. Within Philadelphia, many of the higher education institutions, such as Wharton, host their own summer programs for high school students, including business education programs. Furthermore, particularly in regard to the gap year program, Schoolyard will come into direct competition with higher education institutions and other organizations with established gap year programs. Many organizations run their own programs that range from academic endeavors to travel adventures and practical work experiences; however, with the tested success of Startup Corps, Schoolyard is in a strong position for future success. Additionally, with the determination and experience of its founders, they are up for the challenge.

Impacts of the New Program

The Schoolyard Ventures model has the potential to generate great social impact through its outreach. There are the obvious benefits of starting a business and creating employment and profits. As mentioned previously, David Zamarin’s business alone generated over $25,000 in revenue, and Sharif Tarver’s Philly’s Future Talent has six employees. Many of the fruits of founding a business may only be in the laborers’ future. Immediate benefits of these activities will be felt in city tax revenues and increased employment.

The experience of starting something will no doubt encourage students to continue to found new businesses. Seventy-five percent of all startups fail and of these, 20% fail within their first year; however, 39% of startup founders were previously CEOs or founders of their own businesses. The odds of a first-timer’s success are not in the startup founder’s favor, with only 18% of entrepreneurs succeeding in their first venture. The odds do not improve much after the first failed venture—the success rate only rises to 20% (Walden 2014).

With the guidance of the Schoolyard Ventures program and of mentors who have entrepreneurial experience, one can imagine that the odds of success are swayed more to the student’s side during and after the program. Similar to Rich’s own experiences, students in the program are likely to continue to create businesses, some that are potentially vastly more successful than their first efforts. The overall benefits from starting a business are very difficult to measure, but as demonstrated by the launch of new companies such as Facebook, it can be sizeable. For Philadelphia, the addition of new startups serves to continue to build communities such as N3rd and reverse Philadelphia’s reputation to become a business-friendly city.

There are many indirect benefits associated with Schoolyard Ventures. Rich found that the speed of learning from running a business was much faster than the pace of learning in school. The discipline of running one’s own business, with the written, communication and arithmetic skills required, will undoubtedly have some spillover effects. Although Schoolyard Ventures seeks to challenge traditional credentials, the real-world skills students learn will benefit them in the future. As demonstrated by the effects of the Workshop School on its students, a real-world approach can result in increased college acceptance rates for participating students. The six-year graduation rate for first-time full-time undergraduate students in 2012 was 59% (http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=40). Among those graduates, the median 2012 salary for ages 25 to 32 was $45,500 for a bachelor’s degree or higher versus $28,000 for high school graduates (Pew Research Center 2014). This is a $17,500 gap that has continued to grow from generation to generation.

Licensing the product will provide the opportunity to continue scaling the operations. More students will be reached, and the Schoolyard brand will continue to grow. The overall benefits of the program, however, may diminish as the program continues to expand its licensing platform and moves away from the more personal, hands-on approach of Startup Corps. With the buy-in factor, schools will feel obligated to carry through with the curriculum and give students the opportunity to enjoy the benefits of the program. Furthermore, Schoolyard aims to roll out the program cautiously in what is a very large market for high schools.

The Future

Schoolyard Ventures, through the Startup Corps platform, has demonstrated its success in the past. Schoolyard Ventures aims to continue where Startup Corps left off and scale the program. The licensing platform allows for scaling without taxing manpower resources; however, this platform and the program’s potential benefits will depend largely on the enthusiasm of the staff at each school that will be responsible for implementing the curriculum. Moving outside of Philadelphia will be a challenge as Schoolyard begins to come into direct competition with organizations in regions where their name brand may be unrecognized.

These are challenges that Schoolyard is ready to face. The licensing platform is a positive step toward moving out of the region and replicating the program across the country. Personalities like Rich Sedmak, Christian Kunkel and Richard Binswanger, as well as the participating mentors and instructors, will continue driving Schoolyard. They will also continue to effectively expand the program’s reach and maintain the benefits that students enjoyed through Startup Corps.

The gap year program, when it’s launched, will serve to expand options for graduating high school seniors across the country. The program is an ideal fit for seniors who do not know where their interests lie or have an idea that they have always dreamed of pursuing. As the Schoolyard Ventures brand continues to expand, so will the program’s ability to attract more talent and demonstrate that what they offer is as valuable as (if not more valuable than) the traditional credentials offered by colleges and universities, disrupting the standard approaches to education.

It has been six years since the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the consequential beginning of the recession. In 1979, Jimmy Carter described America as being in a “crisis of confidence,” in the grip of the economic woes of recession and inflation as well as other challenges. America has found itself in a comparable crisis today; however, organizations such as Schoolyard Ventures are teaching youth not to give up in the face of crisis or lack of opportunity but to innovate and build in response to adversity. The future of Philadelphia is bright in the hands of the inspired youth of Schoolyard Ventures. With enough drive, perhaps the platform and the message of this program can spread to youth across the country.

References:

ABC. 2014. “Define Bottle, iReTron, Boo Boo Goo, Henry's Humdingers,” [Television series episode]. In ABC’s Shark Tank. Los Angeles, CA.

Archdiocese of Philadelphia Office of Catholic Education. n.d. Our schools. Retrieved from http://www.catholicschools-phl.org/our-schools/.

Chepurny, G. 2012. N3rd Street: Tech business corridor from Old City to Northern Liberties. Technical.ly. Retrieved from technical.ly/philly/.

Drucker & Scaccetti. 2014. 2-year tax breaks for "Jump Starting" Philly businesses. [Web log post]. Retrieved from www.taxwarriors.com/blog/.

Econsult Solutions. (2013). Quoted in| Philadelphia Business Journal. Philadelphia, PA. Retrieved from www.econsultsolutions.com/.

Lee, D. 2014. 5 years after the Great Recession: Where are we now? Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from www.latimes.com/business.

LightHouse Ohio. 2013. The Benefits of Being A Young Entrepreneur. Shaker Heights, OH: S. Tallamraju. Retrieved from www.lighthouseohio.com/.

The Pew Charitable Trusts. 2013. Philadelphia 2013: The state of the city. Philadelphia, PA. Retrieved from www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/.

Pew Research Center. 2014. The rising cost of not going to college. Washington, DC. Retrieved from www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2014/.

Reyes, J. 2014. Philadelphia’s innovation economy, in 7 charts. Technical ly. Retrieved from technical.ly/philly/2014/07/.

School District of Philadelphia. About Us. Retrieved from http://www.phila.k12.pa.us/about/#schools

United States Census Bureau. n.d. 2012 MSA business patterns (NAICS). Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data.html

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2014. College enrollment and work activity of 2013 high school graduates. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/hsgec.nr0.htm

Walden, S. 2014. Startup success by the numbers. Mashable. Retrieved from http://mashable.com/2014/01/30/startup-success-infographic/

World Class Greater Philadelphia. 2014. On-time graduation. Philadelphia, PA. Retrieved from http://worldclassgreaterphila.org/world-class-index/on-time-graduation.

Get aHead For Business. Young Americans Center. Retrieved from http://yacenter.org/entrepreneurship/get-ahead-for-business/