Summary

When Pact, a Washington, D.C.-based global nonprofit founded in 1971, first invested in innovation in fall 2013, we looked to determine whether we could institute a dedicated innovation team to source and win unrestricted funding for concepts from across Pact’s country and project staff. The nuanced and complex nonprofit system required a thoughtful, systems-level approach to achieve this. With critical local staff already prioritized to projects and without local-level organic, enabling environments for testing and experimentation, success for innovation at Pact was a journey that went beyond dollars and awards, targeting and transforming our culture and processes.

Innovation in the Nonprofit Sector

The notion of a research and development (R&D) or “innovation” team traditionally brings to mind a private sector conglomerate reinvesting millions into market analysis, consumer research, and product development. Competitive markets, demand for profit, and customer acquisition drive private sector companies to invest in R&D teams as best practice. A dedicated, internally funded R&D or innovation team intentionally doing market research, technology investment, or product experiments for competitive advantage is much less common in the nonprofit world, despite a shift in the last 10 years toward incorporating more technology, business acumen, and private sector best practices to achieve social impact.

Multiple factors affect this reality. For instance, by imposing a more rigid program implementation structure, the traditional grant-based business model driving nonprofit operations can inadvertently stymy organic innovation spaces.1 Quick and cost-effective program fixes are favored over experimentation. Additionally, donors’ strong focus on evidence-based solutions can discourage nonprofits from actively pursuing untested ideas.2 Moreover, expenses and investments in the nonprofit realm are heavily constrained and calculated, leaving little room for unrestricted funding for anything beyond program implementation.3

Building a Nonprofit Innovation Practice

Against this backdrop, Pact hypothesized in 2013 that institutionalizing a team and systematic process for an innovation pipeline could enable us to win grants to fund innovation concepts. After much evolution and nearly five years of learning, the hypothesis has largely held true. But, investment in internal staff and seed funds was not enough; the enabling environment for innovation, capacity building, and dedicated project management resources were equally as important. To succeed, an organic innovation ecosystem needed to permeate throughout the organization.

Shortly after pursuing the original hypothesis, we realized that we would need to revisit the value proposition. Country offices and staff lacked several key ingredients of an organic innovation ecosystem: time and funds to innovate, space and permission to experiment, and a culture of experimentation. Though there was strong social capital to engage with the innovation team, without these tenets and with local champions tied to other priorities, headquarters-based innovation staff struggled to develop new concepts.

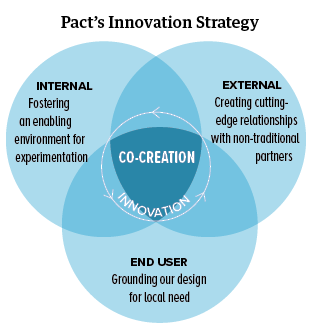

Because of this we strategically pivoted to focus first on creating enabling environments. We developed a three-pronged approach: build internal enabling environments for innovation stemming from the country offices, create external relationships with new partners to co-create new solutions, and use empathetic, participatory techniques, like human-centered design (HCD), to include end-users in co-creating transformative solutions.

Pact’s innovation-focused staff became an official team, functioning as a customer service unit for Pact’s headquarters and country offices and providing ideation techniques, funding opportunities, and project management support to backstop and guide them. We first began sourcing local innovation through an in-country workshop that allowed country teams to build entrepreneurial, creative skills and mindsets while providing a safe and permissive space to experiment. In the first six workshops, the innovation team trained 90 staff, 88 of whom felt that they could apply what they learned in the workshop. And, Cambodia’s resulting governance and accountability digital app received seed funding from USAID within just three months.

Based on these early successes, the innovation team launched a thematic global innovation competition in spring 2016 to foster creativity and friendly competition among the country offices while offering intentional and resourced space to experiment. Two-thirds of country offices participated in the first year, and the second year’s winning idea burgeoned into a revenue-generating project within six months. The combined success of the workshop format and competition demonstrated that an internal incubator, backstopped with technical assistance and capacity building, would be the strongest possible return on investment, allowing Pact to test a variety of concepts and, most importantly, get them ready for external audiences and sustainable implementation.

To this end, in July 2017, Pact launched Ignite,4 an internal incubator and seed fund offering up to $20,000 to test ideas. Applications require market analysis, consumer identification, and a value proposition (rather than a theory of change) to nudge internal innovators to think more entrepreneurially. In its first nine months, the incubator received 15 submissions and funded six concepts; one has successfully incubated and been adopted into existing Tanzanian programming.

Pact’s innovation team continues to grow in its capacity and successes. We have won two million dollars in external seed funding from donors such as USAID, Hewlett Packard Enterprises, and World Bank. We continue to receive accolades; for example, Cambodia’s digital app was featured in Forbes5 and the 2017 competition winner for a reusable sanitary pad social venture6 was accepted into ScaleX accelerator cohort 3. Moreover, innovation and HCD became formalized metrics in Pact’s business strategy beginning 2014, demonstrating our comprehensive commitment to innovation.

Lessons Learned

Pact has stayed true to the principle that innovation must come from country offices to ensure local ownership, efficient implementation, and sustainability. In a conscious effort to avoid “ivory tower” innovation, Pact’s headquarters-based innovation team shares resources and creates partnerships with innovators, but actively seeks to thoughtfully source innovation at its organic entry point in the field. Then, where relevant, we marry external entrepreneurs, innovators, or corporate partners with country offices. As an in-house team, we focus on shifting the entire organization’s culture while sourcing new concepts from the local context that can accelerate social impact.

This cross-section between skill and mindset development coupled with new product and service incubation differentiates what R&D looks like in the social impact sector versus the private sector. Acknowledging that the nonprofit sector is not as agile as other industries forces innovators to ensure that operations within this ecosystem are done with social intelligence, empathy, and thoughtfulness, meeting ideas where they are and providing dedicated funding and services to empower the organization’s intrapreneurs. For Pact, this includes funding a six-person in-house team with cross-sector skills in HCD, gamification, digital development, and social enterprise development. This team’s mandate is developing innovative concepts, managing innovation projects, and connecting new innovations to funding sources.

Initially, Pact hypothesized that we could source concepts for our innovation portfolio that already progressed beyond the seed phase, but this proved false. Pact’s innovation model now centers on making small internal investments in new ideas that are supported by clear hypotheses and market research so that concepts can become ready for an accelerator or angel investor. This approach is critical to success because the traditional proposal-based model does not provide the space, time, or funding for such endeavors.

With this in mind, scale continues to be challenging, largely because adequate funding opportunities are irregular. Small pots of external seed funding for innovation typically require piecemealing projects, slowing implementation of full projects.7 Additionally, inconsistent access to funds forces the team to backburner concepts until resources can be obtained, while losing internal champions as other priorities compete for staff’s already-constrained time. Pact does make a concerted effort to write incubating innovation concepts into traditional donor-funded proposals, but this is challenging because we need to foremost address donor requirements. And, new innovations are often segmented, causing them to lose their original intent and progress.

Despite these challenges, the journey was ultimately transformative. Perhaps greater than Pact’s portfolio of successful innovations is the resulting shift in organizational culture toward innovation. In spring 2017, Pact formally announced our transformation toward an ambidextrous organization that continues to implement our core traditional development model while exploring how to comprehensively operate new business models, such as social enterprises. Pact’s cultural shift predicated our transformation, drawing on our learned ability to manage multiple innovation streams to strengthen our core business model (continuous innovation) while exploring new business models (disruptive innovation).

Now, the entire organization is challenged with incorporating new products, services, and platforms into country portfolios. This has led to greater cross-country collaboration and empowered regional connections and conversations, building critical social capital for incubating concepts and a desire to regionally and globally cross-pollinate those concepts. Despite challenges, we are optimistic that under a transformed Pact, innovation, replication and scale will see unprecedented advancement.

Author Bio

Pact Communications

Michelle Risinger is Director of Innovation at Pact and a founding member of Pact’s innovation team. Risinger focuses on creating enabling environments for innovation and using human-centered design to source solutions with base-of-pyramid end-users.

Works Cited

1 Hilda H. Polanco and John Summers, “Cashflow in the Nonprofit Business Model: A Question of Whats and Whens,” Nonprofit Quarterly (October 2017), nonprofitquarterly.org.

2 Jocelyn Watt, “When Restrictions Apply,” Foundations (blog), March 18, 2015, ssir.org.

3 Ann Goggins and Don Howard, “The Nonprofit Starvation Cycle,” Stanford Social Innovation Review 7, no. 4 (Fall 2009), ssir.org.

4 See http://www.pactworld.org/innovation/ignite.

5 Joshua Wilwohl, “Want To Complain To Cambodia’s Gov’t? There’s An App for That,” Forbes Asia (blog), February 14, 2016 (11:44 pm), www.forbes.com.

6 See www.facebook.com/kozogirls/.

7 Watt 2015.