Contemporary understanding holds that childhood hearing loss is a neurological emergency that has a deleterious impact on a baby’s brain. Consistent auditory stimulation provides the underpinnings for growth of the auditory cortex. Beginning at four months in the gestation period, the ability of the auditory cortex to function and flourish is contingent upon sensory stimulation. Hearing loss of any type and degree interferes with the “doorway” of getting sound to the auditory brain centers. (Cole & Flexer, 2016) Technological advancements in hearing aids and cochlear implants afford greater opportunity than ever for children with hearing loss to develop spoken language. Technology alone, however, is nothing more than hardware without appropriate interventions. When the intent of intervention is development of listening and spoken language, parents need guidance and coaching to maximize technology usage for the children with hearing loss in order to overcome impediments to auditory brain access. The ear is merely a doorway to the brain, the true organ of hearing (Cole & Flexer, 2016).

Hearing loss affects 12,000 children born in the United States each year, making it the most common birth defect. Approximately three in 1,000 babies are born with permanent hearing loss (Ross, et al., 2008, Rousch & Kamo, 2014). Approximately 92 percent of children with permanent hearing loss are born to two hearing parents, while an additional four percent are born to one hearing parent and one parent with hearing loss (Gilliver, Ching, & Sjahalam-King, 2013; Madell, 2014a; Mitchell & Karchmer, 2004). To summarize, 96 percent of children born with permanent hearing loss are born to parents where at least one parent does not have hearing loss. These statistics are relevant in that they highlight a significant reality in educational practice for children with hearing loss: most children who are deaf or hearing impaired are born to, and reside with, families who are likely to initially be ill equipped to address the complexities of parenting a child with a communicative disability (Nicholson, et al., 2014). Nicholas and Geers (2013) note that the vast majority of families whose children are deaf or hearing impaired desire that their child will learn to learn to listen and speak as they do. Accordingly, for parents of children who are deaf and hearing impaired, the urgency of becoming engaged cannot be overemphasized. When a child has a hearing loss, it is crucial for families to provide purposeful, consistent, and enhanced linguistic input in order to mitigate the impact of the auditory deprivation. Decades of education research suggest that as parents become more involved and empowered in the special education process, outcomes for their children improve (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1997; Ferguson, 2008; Fish 2008; Stoner et al., 2005). This knowledge underscores the importance of effective collaboration between parents and educators (Goodall and Bruder, 1986; Epstein, 2001). Fish (2006) emphasizes that educators should seek and use parental knowledge, because no one knows a child better than his or her own parent.

The parents’ journey into the world of supporting a child with hearing loss can be equally difficult, tumultuous, and wrought with opportunities for discouragement. Caught amidst feelings of anger, guilt, and self-doubt, parents begin their journey to determine what they can do to ensure that their child will develop into an independent adult with identity reflection underpinnings of self-esteem and confidence (Luterman, 2003, p.53). Parents are hurled head first into an ocean of acronyms and advocacy, and are expected to function collaboratively within a system that requires trust and connections, to best serve their child’s needs. Typically, parents struggle to decipher medical jargon in an attempt to discover how to best care for, raise, and engage their child. This struggle is compounded by the necessity of evaluating information and weighing possible outcomes in the use of assistive technologies, modalities of communication, and choices in education and habilitation (DesGeorges, 2003; Kurtzer-White & Luterman, 2003). In order to make these difficult decisions with educated choices, parents need accurate, non-biased information regarding communication methodologies and school placements, as these choices set the lifetime trajectory for their child (Madell, 2014a).

The initial shock to the family unit is significant and well documented (DesJardin, Eisenberg, & Hodapp, 2006; Sass-Lehrer, 2002; Zaidman-Zait & Jamieson, 2007; Zaidman-Zait & Most, 2005. According to Sheetz (2004), once hearing parents have confirmed that their child has been diagnosed with hearing loss, they alternate between feelings of pain and disbelief. Luterman (2003) poses that the diagnosis of a hearing impairment is a loss that must be grieved. The abrupt shift in dreams for a parent is real, as parental dreams most likely do not include a child with disabilities. There is, then, a perceived loss, which Tanner (1980) equates to a death in the family, and, as Kubler-Ross (1969) emphasized, there is a great probability of anxiety to manifest in the face of loss. This probability is further exacerbated for parents facing the challenges of raising a child with disabilities, given the chronic and recurring nature of episodic grief.

This small study, which occurred in southeastern Pennsylvania, adds to the body of research that involves family engagement, with a specific emphasis on parents of children who are deaf or hearing impaired. The findings and interpretation of data suggest that practices to facilitate family engagement have been experienced and are appreciated by participants who are served by this regional service agency. The purpose of the study was to identify facilitative practices and obstacles to family engagement as reported by parents of children involved in a hearing support program in a regional service agency. Qualitative methods were employed to analyze responses to a research protocol based on family engagement research practices. The study was based on the assumption that the delineation of factors that facilitate or impede family engagement could ultimately serve to support outcomes for children who are deaf or hearing impaired.

The study used a phenomenological approach to address the research questions:

What do parents of children who are deaf or hard of hearing cite as facilitative practices toward their engagement in the special education process?

What do parents cite as obstacles to their engagement in the special education process?

Participants were selected based on their response to a poll of the larger population of parents of children enrolled in the hearing support program for a single regional service agency in southeastern Pennsylvania. These children have deafness or hearing impairment as the primary disability listing on their Individual Education Plans (IEP). Interview participants represent a selected subset of the overall population of parents of children who are deaf and hearing impaired. They have children who receive hearing support from the regional service agency. All of the children receiving support use amplification (either hearing aids or cochlear implants) and communicate through listening and spoken language. The children ranged in age from five to 19 years old. The children were diagnosed and fitted with amplification as young as six weeks and as old as six years of age. The youngest of the participants’ children had recently entered kindergarten, while the oldest was an entering college freshman at the time of the interview. Of the nine total participants in eight interview sessions, two were fathers, six were mothers, and one was the grandmother of a child who is deaf or hearing impaired. These participants represent eight of the 13 diverse school districts comprising the regional service agency where the research took place, each of which has a distinctive culture, geography, and socioeconomic climate.

Process

This phenomenological study centered on the subjective experiences of the participants (parents of children with hearing loss) to obtain greater understanding and (possibly) meanings of phenomenon and to address questions concerning the everyday lived experiences of parents of children with hearing loss. By collecting information about the shared experiences of this subset of the population, the researcher developed a composite description of the essence of experiencing parents’ perceptions of facilitative factors and obstacles to their involvement in the special education process (Moustakas, 1994). Through listening to their stories, the researcher sought to discover the answers to research questions while establishing a greater understanding of lived experience from the participants’ perspective.

Qualitative research analyzes and interprets data to create a narrative of the results that paints a vivid picture of the research findings. By conducting this research within a designated subset of the population of parents of children with disabilities, the researcher obtained program-specific data regarding practices described as facilitative or impediments to family engagement in the special education process (OSEP, 2011, p.107). For this study, parents of children who are deaf or hearing impaired and served by a regional service agency program were examined. Such data is not typically available because Pennsylvania’s School Performance Plans (SSP’s) are developed by each individual school district, while this regional service agency encompasses thirteen distinctive districts. Therefore, aggregate data of this nature had not been previously collected. Most significantly, the intent of this study was to give voice to the parents of children who are deaf or hearing impaired by eliciting their thoughts on facilitative practices and obstacles to their engagement in their child’s hearing support program. The ultimate goal was to enhance support to families on the journey of parenting a child with a disability, improving service through identifying practices to foster or avoid within the service delivery model.

Research Process

As the director of the program being studied, the researcher was keenly aware of the critical importance of transparency in data collection and the interview process. The Executive Director provided written endorsement of the plan to conduct this study. Furthermore, the premise and procedures to be utilized in the study were provided to program staff. This was done to provide assurance to teachers and other staff members who were likely to have concerns about survey outcomes. The capacity to leverage the knowledge acquired through this study as a change agent to enhance organizational practices served as a beacon throughout the research process. Professionals on the hearing support team were invited to view survey questions prior to study commencement, enlisted to support dissemination of the survey, and were kept abreast of the outcomes as the study progressed. Transparency throughout the study process was intended to facilitate buy-in, because study results were intended to be utilized as a springboard for ongoing staff reflection and growth. Through exploration of the phenomenon of family engagement in the special education process, challenges to effective engagement were illustrated, thus spearheading efforts to mitigate those impediments. Most notably, a celebration of the practices that are cited as effective have provided the groundwork for multiplying their impact. With a focus on those practices that support family engagement, efforts to expand those practices have intensified, ultimately enhancing programming for the students in this program and, potentially, for other practitioners similarly situated.

As the individual interviews progressed, the study participants appeared willing to share their intimate feelings about parenting a child with hearing loss. They shared the raw, emotional recognition of loss of the children they expected, and the celebrations of their children’s growth and achievements. Their statements provided meaningful insight to the experiences of parenting a child with a hearing loss, and have implications for those who serve all children with special needs. In listening to the parent’s narratives, we can all learn.

Participant interviews revealed the following facilitative practices which were described as supporting engagement in the special education process:

- Parents acknowledged the value they place on strong and consistent communication with the teacher of the deaf child as well as with the General Education team. They appreciate the ability to utilize multiple modalities to keep in touch, including email, voicemail, texts, and face to face conversations. Regardless of the methodology determined, accessibility to professionals is key.

- From the moment of diagnosis, parents crave information about hearing loss and its implications. They want “just in time” information that supports decision-making, understanding communication options, IDEA procedures, and their child’s rights relative to special education. Support in acquiring this information facilitates parents’ ability to effectively engage in the special education process.

- Participants realized the generative value of making connections. As previously noted, more than 95 percent of parents of children who are deaf or hearing impaired have typical hearing themselves, and therefore have little or no experience with the challenges inherent with an impaired auditory system. Understanding is facilitated when families are able to effectively forge networks of support with professionals, other parents, and organizations that afford the benefits of experience with hearing loss.

- Participants in this study were emphatic in their discussions of amplification and the value that technology beings to their children’s lives. The participants spoke highly of the intensive support received from the teachers of the deaf and educational audiologists of the regional service agency from the time of diagnosis and initial access to hearing aids or cochlear implants through to selection of high-tech assistive devices. In addition, they acknowledge the value of our agency’s proximity and collaboration with a local children’s hospital. Of particular note was discussion of the willingness of the regional service agency to support ongoing understanding of technology advances through ongoing professional development.

The advocacy afforded to their children, as well as training to develop their child’s self-efficacious behaviors, is cited as facilitative by the parents in this study. In particular, parents are appreciative of the early connections that are prompted by professionals from this regional service agency.

In addition, the data points to several obstacles to engagement that were noted by the participants. Subjects of the study related several situations or issues that proved to be impediments or obstacles to engagement.

Parents stated that weak, non-productive partnerships with general or special education staff members were definite barriers to a sense of engagement. Feeling that their opinions, concerns, or ideas were insignificant or dismissed served to weaken or damage the relationships that are crucial to effective partnerships. While comments of this nature came from a minority of those interviewed, the deleterious impact on parents who felt disenfranchised lasted many years after the actual event.

- Participants cited a lack of knowledge as an obstacle to engaging on their child’s behalf. This knowledge may encompass information on hearing loss, on communication modalities, or on the IEP process. When information was readily available, parents cited this as facilitative. Conversely, parents who felt that such information was not provided by their child’s teacher of the deaf, or that it was offered inconsistently, or at inappropriate moments in time, felt unprepared to effectively engage as an advocate on their child’s behalf. Parents who did not participate in early intervention, whether due to late identification or physical absence from the service, felt less competent in understanding their child’s hearing loss. Moreover, all families noted that directed activities and information on the needs of older students occurred less frequently although these were desired. Additionally, parents sought a forum to convene and opportunities for their children to know and engage with other children with hearing impairments.

- Confidence and competence relative to amplification technology was defined as an obstacle by some participants, despite overall positive feelings about the value of technology. Parents shared concern about keeping up with the intense speed at which amplification technologies evolve. They worried about inconsistent use of technology at school by teachers who do not recognize or understand the value of the devices. General education teachers were most often sighted as lacking in competence or desire to deploy technology, but one parent indicated that her child’s teacher of the deaf did not exude adequate confidence in the ability to set up, utilize, and educate others about her son’s frequency modulation (FM) amplification equipment. Teachers who failed to sustain the necessary professional development to stay abreast of technology changes were considered an obstacle to effective engagement by parents in this study.

In Beyond the Bake Sale: The Essential Guide to Family-School Partnerships, Mapp, et al (2007) defined possibilities for family connections along a continuum that begins with involvement and peaks with empowerment. They define family involvement as participation in school-sponsored activities, such as back to school nights and sporting events. Engagement involves participation in committee work or surveys, and opportunities for shared decision-making. Empowerment, the pinnacle of family connectedness, involves organizing or advocacy at school and community levels. Educational leaders are responsible for recognizing the need, and then to cultivate empowerment of families in their charge. An examination of social and cultural capital as facilitators to engaging families in the education process will support those efforts.

Parent engagement is a multiplier for student success, the power of which cannot, and should not, ever be underestimated. Investment in supporting engagement is worth the commitment of time and energy because engaged parents serve as connectors (Dow, 2010). In the proverbial village, the importance of effective engagement is evident. As parents expand their personal capacity, they expand their potential impact for their own children, as well as other children whom they encounter in neighborhoods, on the soccer fields, and throughout the broader community.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act is the key piece of legislation for students with differing abilities (IDEA, 2004), IDEA amplifies the effectiveness and potency of educational legislation and defines the need for parents to be involved in the Individual Educational Program (IEP) process relative to evaluation, development, and implementation, as well as placement decisions. Moreover, IDEA requires that parents must be equal partners, not only on the IEP team, but also with representation in matters relative to district, state, and federal policymaking. To do so, parents must be informed and engaged partners in their child’s education.

Parent engagement is not only a legal requirement of IDEA (IDEA, 2004, PL 408-446), it is also an evidence-based best practice. Family engagement efforts have taken a larger share of the spotlight with each iteration of educational legislation, including the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB, 2001) and the most recent update of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA, 2015). This legislative update recognizes that children live in the context of families and that strong family engagement is central (rather than supplemental) to promoting student success. The realization that professionals will come and go in a child’s life, but that the family remains a constant, serves to inform the notion of empowering the family (Robbins & Caraway, 2010).

Effective partnerships between families and schools are enhanced by reciprocity and trust, and ultimately, both parties benefit from the enhanced relationship. Of course, the most significant beneficiary of enhanced school-home and community relationships is the student. With intentional, ongoing emphasis on fostering partnerships, trust must never be taken for granted. Family engagement is enhanced through the development of social and cultural capital.

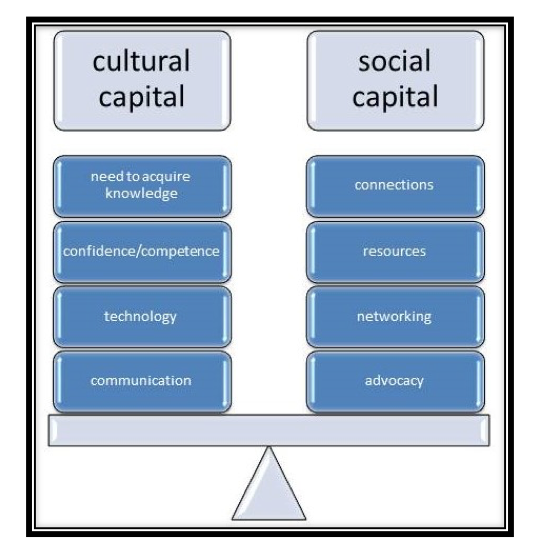

To begin, when one’s child is diagnosed with a hearing loss, parents must act swiftly to first acquire and then actualize the cultural and social capital necessary to procure outcomes or influence on behalf of their children. Cultural capital, first conceptualized by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1986), includes those non-economic resources that enable social mobility. Examples of cultural capital include knowledge, skills, and education. Bourdieu also states that social capital includes resources that an individual obtains by being part of a network of social connections. Both concepts hold that social networks and culture have value. Audrey Trainor (2010a) has noted the critical importance of all forms of capital regarding home-school interactions, but cites challenges in establishing this capital, stating that meaningful participation in the special education process necessitates a balance of power and status between home and school. This balance can be achieved through parental acquisition of social and cultural capital, which offers them entre to the field. Each of the parents interviewed alluded to the need for knowledge and information when discussing their child’s diagnosis with hearing loss. This quest for understanding is urgent and real as it forms the foundation for the acquisition of cultural and social capital.

Social capital is an attribute of organizations that focus on norms and trust. Trainor (2008) notes that social capital plays a significant role in the lives of individuals who are at risk of being marginalized, emphasizing the importance of formal and informal support networks. Study participants echoed this importance. This capital is considered to have trading value that can be exchanged for intellectual and economic growth, which can lead to enhanced emotional satisfaction and autonomy in decision-making. In connecting with others with established social capital, families who join local clubs, advisory groups, and national organizations amass not only individual social capital, but simultaneously accrue benefits from the greater pool of capital possessed by the larger group. Social capital, like other forms of capital, is readily transmitted from parent to child (Bourdieu 1986). Consideration of the concept of cultural and social capital provides a structure for the examination of study results.

In their responses to interview questions, participants shared experiences and anecdotes that were analyzed to derive recurring topics and themes. These themes include practices that are perceived to facilitate engagement, such as communication, acquisition of knowledge, partnership, technology supports, and advocacy. Obstacles to engagement include weak or non-existent partnerships, a lack of information, and varying issues surrounding technology. As parents acquire cultural capital in the form of knowledge and skills, one can assume that that this knowledge can be activated to cultivate social capital to further support their engagement. Under this assumption, the themes that emerged through the interview process relative to facilitative practices and obstacles to engagement are depicted below through the lens of cultural and social capital. Parents, 95 percent of whom are initially unprepared for dealing with their child’s hearing loss, seek equilibrium as their journey commences. This equilibrium is attained as they acquire the knowledge and skills essential to propel them toward effective engagement. Once established, this equilibrium can be disrupted during periods of transition, and so the delicate balance must be attended to. Parental self-efficacy supports the empowerment required to seek what one needs (DesJardin, 2007). Nevertheless, educators must remain vigilant in their support of families through the lifespan.

Figure 1: Figure & Social Capital

The discussion of cultural capital as applied to parents of children who are deaf or hearing impaired brings focus to the critical importance of parent’s knowledge of, and disposition towards, special education law and procedure, understanding of technology, and about resources to support them on their journeys. Findings support the establishment of a family engagement policy for the regional service agency in the study, as well as for local school districts and other organizations that are charged with supporting families of children with all disabilities. Development of a detailed family engagement policy is highly recommended. It is suggested that data derived from this study can inform the process of assessing school-facilitated family engagement by expanding the process of asking questions. Families involved in this study were delighted to participate, and all noted that they appreciated the opportunity to share their opinions and stories about the engagement process. The mere process of asking for feedback can be considered facilitative, as it drew parents into the conversation and fostered partnership with the interviewer. Regular opportunities to discuss their perspectives are recommended as a practice to bolster family engagement.

Facilitative practices were frequently mentioned by the participants from families with children whose hearing impairment was identified through newborn screening and were served by early intervention services until entering school-aged programs. In contrast, for three of the eight families whose children’s hearing impairment were identified later than three years of age, the themes of need for knowledge, resources, and advocacy were referenced as obstacles. These important practices were impeded because school-based services were not necessarily family-focused when compared to the family-centered, home-based programming mandated for early intervention. Just as their children do, parents benefit from early identification and family-centered supports. It is recommended that program planning support family needs across the lifespan. Customized programs and additional focus on families whose children are identified later in life could be ensured by meeting families at their respective points of entry to the service delivery system.

Parents in this study were generally satisfied with communication from their teacher of the deaf, but at least one parent suggested that they would appreciate more informal correspondence to share good news, citing that most correspondence centered on dealing with problems or issues. Regular, meaningful, two-way communication is an essential component of family engagement. Parents must feel that their input is important, and that it has value in the development and implementation of their child’s Individual Education Plan. These findings, therefore, serve to inform future program development.

Obstacle to Opportunities

The findings of this study provide insights to the experience of parenting a child who is deaf or hearing impaired. Information from this study affords an understanding of parental perceptions of facilitative practices and obstacles to family engagement in the special education process.

Participants noted that consistent, proactive, two-way communication was an essential component of effective engagement. Multiple means of communication were noted as effective, including phone calls, text messages, and emails. Of particular note, was that participants expressed a desire to receive information not only when there were problems or negative issues that needed to be addressed, but also when good things were happening as well.

Similarly, participants indicated that evolving, timely, and ongoing acquisition of knowledge was crucial to engagement in their child’s program. Understanding of the IEP process, implications of the hearing impairment, and expectations for programming were among the needs cited as facilitators. Participants were resoundingly clear in their assertions that the need for knowledge is constant, that it evolves across their child’s lifetime, and that supports provided to expand that knowledge base are highly valued.

Additionally, participants stated that they valued the connections that they forged along the journey of parenting a child with hearing impairment. Parents considered these connections, with professionals as well as with other parents of children with hearing loss, to be strong contributors to their ability to develop self-efficacy relative to their parenting roles. These connections were noted to be equally important for their children. School-facilitated opportunities to make these connections were explicitly requested by the participants on their children’s behalf. Networking allows for the simultaneous acquisition of cultural and social capital, and cannot be underestimated as a facilitator of engagement.

Furthermore, participants lauded the value of amplification and assistive technology, including hearing aids, cochlear implants, and FM systems; yet the parents noted the particular challenges of keeping up with the rapid, constant advancements in the field. Feeling less than fully competent with technology was a source of frustration and anxiety. Parents seek sustained support to stay abreast of changes in hearing technologies in order to assure optimal auditory brain access for their children.

Participants also contended that developing the ability to advocate was a necessary precursor to engagement. Advocacy skills were acquired as a function of confidence and competence regarding their understanding of their child’s hearing loss.

Cultural capital takes the form of:

- Understanding implications of their child’s loss;

- Understanding auditory brain access;

- Technology in the form of hearing aids, cochlear implants and FM systems;

- IDEA regulations;

- Safety; and

- Social implications of hearing impairment.

As this capital was acquired, participants became empowered to assume their roles as advocates for their child. When leveraged, this empowerment has propelled participants to expand their advocacy to state and national levels

Family engagement when children are deaf or hearing impaired must be viewed in the context of a changing landscape. Static processes for delivering support of family engagement must be replaced by dynamic, collaborative partnerships that successfully leverage and harness the impact of empowered parents. From this research, it can be surmised that the obstacles cited can be viewed as opportunities for growth and improvement that will enhance outcomes for all children. The findings of this study are a call to action to promote transformational leadership by eliciting the investment of time, resources, and energy that focus on family engagement as the foundational component of all educational endeavors. The study’s participants had self-identified as effectively engaged in the special education process, and so their responses provide validity for that subset of the population. The goal of this study was to explore the lived experiences of parents of children with hearing loss by listening carefully and hearing their voices in order to inform continuous program improvement. Results are being used to guide emerging practices, to strengthen those that need attention, and to inform local, state, and national policies.

Families arrive at the special education doorstep with empty backpacks, unaware of what they need and uncertain about how to acquire what they need. They fear for their child’s safety in light of the implications of their hearing loss. Families crave connections with knowledgeable professionals and others who recognize their needs and can support them in building capacity to support their children. Social and cultural capital are amassed through these connections, and it is this capital that facilitates self-efficacy to become empowered advocates on behalf of their children.

Transitions through the life cycle, whether from preschool to kindergarten or from college to career, are periods when the intensity of need resurges. Educational providers are reminded that family needs are strongly influenced by the family’s current place in their journey, and that supports must be customized to the timing of those needs in order to ensure their effectiveness. Professionals are further reminded to tailor the levels of support and encouragement that they afford during times of educational transition, as a family’s needs and challenges resurge.

Innovative models that place educators in partnership with parent and community organizations, as well as businesses and foundations, must be established to develop synergistic, sustainable collaborations that strengthen educational outcomes for children. In the regional service agency where this study occurred, the following actions have been deployed:

- Consideration of parents’ thirst for understanding in the early stages of partnership, and that their needs will constantly evolve. As adult learners, parents’ learning styles must be acknowledged and honored in order for interventions to be effective.

- Focus on the importance of cultural competence by embracing all types of parenting, including grandparents, who are at times in a triad relationship with their own child as well as the child with hearing impairment. Educators who have knowledge, skillsets, and attitudes that embrace the diversity of students and their families are better poised to cultivate their strengths.

- Recognition that (when present) both parents in a couple need to experience customized opportunities to learn and that this points to the need for flexible scheduling and delivery of services.

- Consideration to reframing teacher workdays, allowing for flexible schedules that enable teachers to meet parents where their needs are. Recognition that the teacher workday need not be locked, but rather should allow for accommodating opportunities to connect with families at varied times of the day, whether in person or via telepractice (Houston, 2014).

- Activation of the concept of a growth mindset in reviewing the findings of this study in order to move the organization from good to great relative to family engagement.

Participants in this study shared their perceptions of practices that facilitate their ability to engage. In the context of interviews, they also cited factors that have impeded this engagement. The voices of parents in this study were unified in desiring consistent, two-way communication that is customized to their child, and matched to their personal needs on the parenting journey. Participants called for intensified efforts to address transitions across the educational lifespan, whether from early intervention to kindergarten, or from high school to college. They seek expertise in support of amplification equipment. They particularly cite reliance on their children’s teachers of the deaf to impart confidence and competence to them and their children, noting the rapid and continuous advancements in the field. Parents thrive on information, connections, and partnerships that develop self-efficacy in accruing the social and cultural capital that are the keystones of their children’s success.

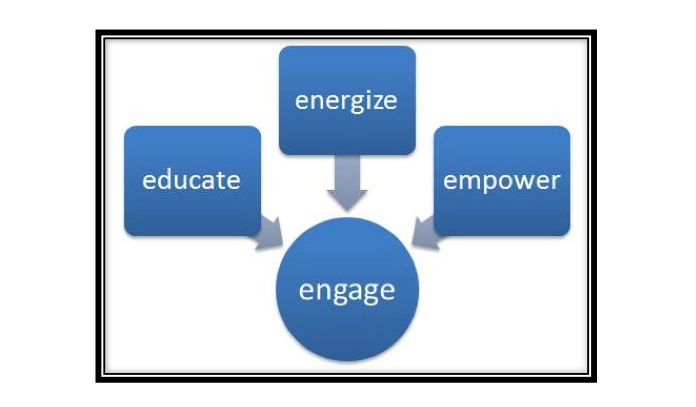

Figure 2: Contributors to Engagement

Engagement efforts must extend beyond random activities; rather, they must form the core of a clearly articulated structure of service that allows for synergistic growth and perpetual forward motion. Activities that are linked to learning, such as literacy nights or technology fairs, are most likely to produce effective outcomes. Opportunities to learn side-by-side with educators will promote competence, confidence, and self-efficacy for families. Events that involve follow up or are part of a series of events with deliberate plans to integrate active participation will also bolster sustainable growth.

Articulation of vision, policy, and framework that nurtures parents will enhance their partnership with the school and the greater community, ensuring the well-being of not only their own children, but of all children that the parent encounters. Parent engagement is a multiplier for student success, the power of which cannot, and should not ever, be underestimated. Investment in supporting engagement is worth the commitment of time and energy because engaged parents serve as connectors (Dow, 2010). In the proverbial village, the importance of effective engagement is evident. As parents expand their personal capacity, they expand their potential impact for their own children, as well as other children whom they encounter in neighborhoods, on soccer fields, and throughout the broader community.

Works Cited

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The (three) forms of capital. In Richardson, J. (Ed) Handbook of Theory and Research in the Sociology of Education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Ching, T. Y., & Dillon, H. (2013). Major findings of the LOCHI study on children at 3 years of age and implications for audiological management. International Journal of Audiology, 52(0 2), S65–S68. http://doi.org

Cole, E., & Flexer, C. (2016). Children with Hearing Loss: Developing Listening and Talking, Birth to Six (3rd ed.). San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing, Inc.

DesGeorges, J. (2003) Family perceptions of early hearing, detection, and intervention systems: Listening to and learning from families. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 9, 89–93.

DesJardin, J., Eisenberg, L. & Hodapp, R. (2006). Sound beginnings: Supporting families of young deaf children with cochlear implants. Infants and Young Children, 19(3), 179-189.

DesJardin, J. & Eisenberg, L. (2007). Maternal contributions; Supporting language development in children with cochlear implants. Ear and Hearing, 28, 456-469.

Dow, L. (2010) Six Degrees of Connection: How to Unlock Your Leadership Potential. Leadership. Philadelphia: LEADERSHIP Philadelphia.

Epstein, J. (2011). School, Family and Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Improving Schools (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Westview Press.

Epstein, J. L., Sanders, M. G., Simon, B. S., Salinas, K. C., Jansorn, N. R., & Van Voorhis, F. L. (2002). School, Family and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Epstein, J. L., & Ebrary, I. (2010). School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Improving Schools. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015. Public Law 114-95. U.S. Code 20 2015. § 1000 et seq.

Fish, W. W. (2008). The IEP meeting: Perceptions of parents who receive special education services. Preventing School Failure, 53(1), 8-14. doi:10.3200/PSFL.53.1.8-14

Flexer, C. (2014). Auditory brain development: The foundation of spoken language development for all children. Presented at Hear It Here Conference.

Gilliver, M., Ching, T.Y., and Sjahalam-King, J. (2013). When expectation meets experience: Parents’ recollections of and experiences with a child diagnosed with hearing loss soon after birth. International Journal of Audiology, 52(2), s10-s16. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.825051

Goodall, P. & Bruder, M.B. (1986) Parents and the transition process. Exceptional Parent, 16(2), 22-28.

Hart, B. & Risley, T. (1995). Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experiences of Young American Children. Baltimore, MD: P. H. Brookes.

Henderson, A. T., Johnson, V., & Mapp, K. L., & Davies, D. (2007). Beyond the Bake Sale: The Essential Guide to Family/School Partnerships. New York, NY: The New Press.

Hoffman, M. M. (2015). Public sector mission, private sector mandates: An exploration of educational service agencies as entrepreneurial entities (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. AAI3704011)

Hoover-Dempsey, K. & Sandler, H. (1997) Why do Parents become involved in their children’s education? Review of Educational Research, 67(1), 3-42.

Houston, K.T. (2014). Telepractice in Speech-Language Pathology. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing, Inc.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA) of 2004. Public Law 108-446. U.S. Code. 20 2004. § 1400 et seq.

Kuber-Ross, E. (1969). On Death and Dying. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Kurtzer-White, E., & Luterman, D., (2003). Families and children with hearing loss: Grief and coping. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 9(4): 232–235.

Luterman, D. (2003). Counseling families of children with hearing loss and special needs. The Volta Review, 104(4), 215-220.

Luterman, D. (2015). Being truly family-centered. The ASHA Leader, 20(11), 96. doi: 10.1044/leader.FPLP.20112015.96.

Madell, J. R. (2014a). Parents of deaf children need accurate information. The Hearing Review, 21(10), 12. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com

Mapp, K. L. (2015). The dual capacity framework for family-school partnerships. Keynote address presented at Annual Family Engagement Conference “Supporting Strong Partnerships for Children’s School Readiness & Achievement” sponsored by Pennsylvania Office of Child Development and Early Learning, Harrisburg, PA.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Nicholas, J. G., & Geers, A. E. (2013). Spoken language benefits of extending cochlear implant candidacy below 12 months of age. Otology & neurotology: Official publication of the American Otological Society. American Neurotology Society & European Academy of Otology and Neurotology, 34(3), 532–538. http://doi.org

Nicholson, N., Shapley, K., Martin, P., Talkington, R., & Caraway, T. (2014). Trekking to the top- Learning to listen and talk: Changes in attitude and knowledge after a family camp intervention. The Volta Review, 114(1), 57-82.

Roush, J., & Kamo, G. (2014). Counseling and collaboration with parents of children with hearing loss. In J. R. Madell & C. Flexer, (Eds.), Pediatric Audiology: Diagnosis, Technology, and Management, 2nd ed. (378-388). New York, NY: Thieme. Medical Publishers.

Sass-Lehrer, M. (2002). Early beginnings for families with deaf and hard of hearing children: Myths and facts of early intervention and guidelines for effective services. Washington, D.C.: Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center, Gallaudet University.

Sheetz, N. (2004). Psychosocial Aspects of Deafness. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Tanner, D.C. (1980). Loss and grief: implications for the speech-language pathologist. ASHA, 22, 916-922.

Trainor, A. (2008). Using social capital to improve postsecondary outcomes and expand transition models for youth with disabilities. Journal of Special Education, 42, 148-162.

Trainor, A. (2010a). Diverse approaches to parent advocacy during special education home-school interactions: Identification and use of cultural and social capital. Remedial and Special Education, 31(1), 34-47.

Zaidman-Zait, A., & Jaimason, J. (2007). Providing web-based support for families of infants and young children with established disabilities. Infants & Young Children, 20(1), 11–25.

Zaidman-Zait & Most, T. (2005). Cochlear implants in children with hearing loss: Maternal expectations and impact on the family. The Volta Review, 105, 129-150.