Exciting opportunities on the horizon could allow Philadelphia’s Community Development Corporations and hospitals to work together to achieve healthier, safer and more equitable communities.

Exciting opportunities on the horizon could allow Philadelphia’s Community Development Corporations and hospitals to work together to achieve healthier, safer and more equitable communities.

The passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 brought sweeping changes to our nation’s healthcare system, providing access to healthcare for millions of formerly uninsured Americans. One critical, but often overlooked, feature of the reform addresses how hospitals maintain their nonprofit status.

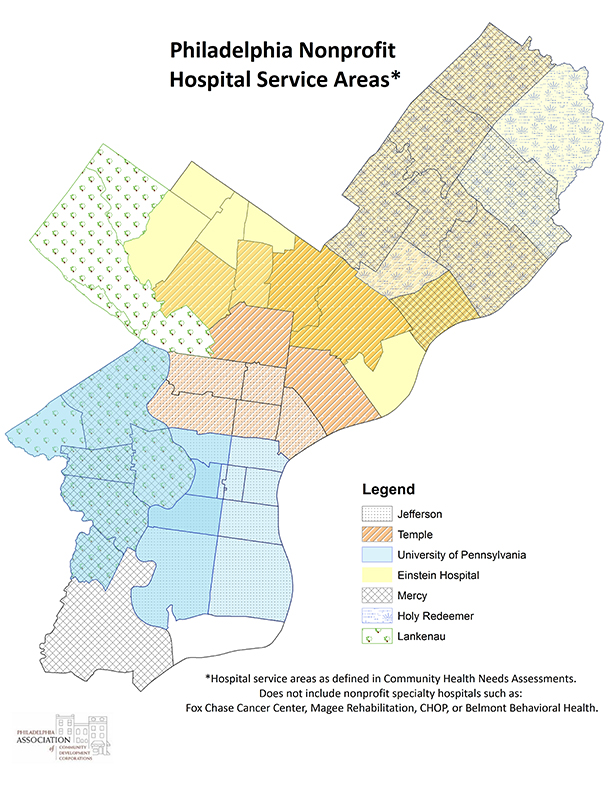

With the ACA’s insurance mandate and increased enrollment for government-run insurance programs, nonprofit hospitals will no longer meet their charitable obligations by primarily providing care to the uninsured. Instead, every three years, nonprofit hospitals are required to conduct Community Health Needs Assessments (CHNAs). Ideally, these are comprehensive analyses of the range of unmet health needs facing the community that the hospital serves. The process involves analyzing health and census data, and meeting with a broad range of community groups to get an on-the-ground perspective. Following the CHNA process, hospitals then develop Implementation Plans which identify the unmet needs they intend to address and how they plan to accomplish them.

The first CHNA process began in 2012, so nonprofit hospitals are again working to update these plans in Philadelphia. The regional office of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services has convened a working group of stakeholders including hospitals, university Public Health Departments, and planning and community development advocates to discuss how to ensure a collaborative and inclusive process.

As a part of this working group, PACDC hopes to see hospitals partner in the work of CDCs in their communities and view CDCs as a resource for engaging with their communities, and for CDCs to view hospitals as partners in achieving shared community goals.

Social Determinants of Health

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ninety percent of healthcare outcomes have nothing to do with what occurs in a clinical setting. Rather, they are determined by behaviors and factors that impact the mental and physical health of individuals. Primary among these are what are known as the social determinants of health which, as defined by the World Health Organization, “are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age…These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources...”

These are the factors that lead to the health inequalities we see today. Americans that live in impoverished communities are more likely to suffer from a variety of ailments, and likelier to do so at an earlier age than those who are middle class or affluent. Some of this, like smoking, is behavioral, but much has to do with the fundamental realities of poverty: exposure to environmental contamination in substandard housing, inability to acquire healthy fruits and vegetables due to lack of access or income, exposure to routine violence, psychological stress from un-or-underemployment and financial concerns, unstable living situations or interpersonal relationships, and so on.

By working to address these underlying conditions, we can better the lives of individuals while reducing the cost of healthcare inequalities in outcomes. Take for example a family living in a dilapidated house with a leaky roof that gives rise to persistent mold. Perhaps they are renters and the landlord refuses to remediate the problem, or perhaps they are low-income homeowners without the disposable income to fix it themselves. This sounds like a housing problem exclusively, right? But consider that their child has developed asthma as a result of the mold. At the first attack, they rush him to the ER and get treatment – and a prescription for refills of an emergency inhaler. But since the mold remains, he must use the inhaler regularly and goes through the prescription quickly. Some months, they can’t afford the $45 to get the prescription filled at all. In these months, they hope he can suffer through a low grade attack but will go to the ER if the attack gets severe. In this way, what started as a housing quality issue has become a health issue detrimental to the life of a single child, a burden to an entire family and expensive for society as a whole.

There is an opportunity for Philadelphia health systems to place increased emphasis on social determinants of health and community building as a part of their CHNAs and Implementation Plans, including supporting the ongoing work of community groups. And there is an opportunity for CDCs to embrace the critical role that they have to play in improving health outcomes in the communities that they serve.

CDCs On The Front Lines of Community Health

CDCs are already well positioned to take a lead role in improving the health outcomes of the neighborhoods that they serve. After all, the work that CDCs do on a daily basis directly addresses those critical social determinants of health.

We know that when a family lacks access to safe, quality housing that they can afford, it can have dramatic impacts on both their mental and physical health – through exposure to substandard conditions, having to prioritize rent over basic necessities like healthy food, and the day in, day out stress of not being sure how much longer they’ll have a roof over their head or what else they might need to go without to keep their family where it is.

We know that when neighborhoods are steeped in urban blight and decay, the health of the whole community suffers alongside it. Crime is encouraged, residents feel the stress of being under siege, and they restrict their time outdoors. But when vacant lots are greened and the blight removed, people feel more positive about their community, crime goes down, and people feel safer enjoying time outside.

Similarly, we know that unemployment and underemployment are problems that confront not just individuals but entire communities. They’re associated with decreased expenditures on nutritious foods and healthcare needs, increased stress with adverse mental health effects and overall negative health outcomes. CDCs work to improve the local economy of their neighborhoods by maintaining and improving commercial corridors and assisting small businesses, making commercial development investments and conducting workforce training. Together, these not only create jobs and help more community members find work, they make a more vibrant community by increasing the goods and services available.

Direct Work in Healthcare

While the daily, bread and butter activities of CDCs improve the health outcomes of the communities that they serve, some CDCs are working more directly to improve the health of neighborhood residents.

For instance, HACE partnered with Mercy Health Systems to create the Mercy LIFE Center – a 17,000- square-foot health services center for low-income seniors. The center, adjacent to two HACE senior housing developments, includes a senior day center and is a cornerstone of HACE’s community revitalization plan which seeks to ensure seniors are able to age in place in their Eastern North Philadelphia community.

Likewise, when Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha (APM) planned its award-winning transit- oriented development, Paseo Verde, they strove to ensure that it positively impacted the health of the surrounding community. A 206,000-square-foot mixed-use, LEED Neighborhood Development Platinum Certification development, Paseo Verde reserves about half of its apartments as affordable units. In the available commercial space, they worked with Philadelphia Health Management Corporation to establish a Federally Qualified Health Center as well as APM’s foster care program and a retail pharmacy to ensure a one-stop-shop for health needs. Paseo Verde’s position adjacent to the Temple University transit hub ensures accessibility to low-income Philadelphians beyond the immediately surrounding community.

However, some CDCs are working to address health outcomes from a different angle. Many communities in Philadelphia have a well-documented lack of access to fresh, healthy fruits and vegetables. In these communities, the primary purveyors of food are the local corner stores which are more likely to carry high calorie, high salt, and high fat nonperishable foods over an array of nutritious, fresh produce. The Enterprise Center CDC is working to address this through their West Philly Foods initiative. They converted an 11,000 square foot vacant lot into an urban farm that has, to date, delivered over 26,000 pounds of healthy produce to community members.

Healthcare Alliances

CDCs can form powerful partnerships with hospitals precisely because so much of what determines health outcomes has nothing to do with what happens in a clinical setting but rather what happens outside the walls and off the campus of the hospital. The number of large nonprofit hospitals with overlapping borders presents excellent opportunities for a mix of innovative collaborations amongst each other and with CDCs.

A number of CDCs have already established productive relationships with local hospitals. For instance, Project HOME has developed a relationship with Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals. Together, they established the Hub of Hope in Suburban Station. The walk-in clinic provided a space in a location that the homeless congregate where they could get physical and mental health evaluations, and referrals for medical, housing and social service needs. From there, the collaboration deepened and in 2014, they opened the Stephen Klein Wellness Center, a Federally Qualified Health Center, in a critically underserved neighborhood of North Philadelphia. Among other things, the state of the art 28,000- square-foot facility provides medical and behavioral health services, a pharmacy and a YMCA.

But partnerships between CDCs and hospitals can be targeted toward more than the direct provision of healthcare services. Opportunities exist for a wide range of collaborations. Take the example above of the child with asthma. Instead of a hospital alone treating the recurrent symptoms of the condition, imagine a bold partnership between hospitals, CDCs and the local Public Health Department to eliminate the defect in the client’s home that is causing the condition. A problem that could have made the home uninhabitable is resolved, stopping the house from sliding into long-term vacancy, the health and wellbeing of a child is improved and hospital resources need no longer be expended on his emergency care.

Looking to the Future

Building on a meeting between staff from Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals and CDCs, PACDC partnered with the hospital and LISC to sponsor a forum for community development practitioners, health practitioners, and City officials on the intersections of health and community development and the ways that these groups can partner to achieve shared goals such as these. As a follow up to that forum, PACDC plans to have more events over the next year and half to introduce CDCs and hospitals and educate both on the value and possibilities in productive collaboration.

It’s important to note that nonprofit hospitals are not required to form these partnerships and make investments to address social determinants of health. They are given a rather wide berth in determining which needs they will address and how they will go about accomplishing the goals that they outline. It is up to CDCs, advocates, and local government to convince hospitals that when they partner with a wide range of stakeholders to improve the context in which neighbors live and the quality of lives that they lead, that the hospitals benefit as well by helping to create safer, more inclusive neighborhoods that do much to address the acute and long-term health outcomes of their communities. Hospitals are massive institutions that change course slowly and thoughtfully, but the progress that’s been made so far in the ongoing CHNA and Implementation Plan development process demonstrates that we should look forward to a future of strong and active partnerships between health systems and the CDCs in their neighborhoods.

Garrett O’Dwyer is the policy & communications associate at the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations.