Executive Summary

The social sector in the United States has a rich history of connecting communities and individuals with vital resources to combat many of the day’s most crushing social issues. Amidst today’s increasingly competitive funding landscape and regulatory hurdles, however; the sustainability of nonprofits as the beacons of effecting social change is often challenged. To ensure the social sector’s viability, a new model of business development has emerged, combining both social impact with financial accountability and inspiring sustainable enterprises capable of remedying many social ills while growing in both scope and scalability.

Social enterprise is an emerging field gaining traction because it encompasses the passion and commitment of the social sector with the business and financial savvy of the private sector. Nevertheless, with many of today’s most passionate and talented visionaries within the social sector lacking the formal business training of their for-profit counterparts, how can they receive the knowledge and skillset to pursue social enterprise as a means to effect positive social change?

The Social Innovations Lab, based in Philadelphia, PA, is an idea incubator and lab that provides social visionaries with the training and education to create social innovations and social enterprise using entrepreneurial principles. Founded by established social entrepreneurs Tine Hansen-Turton and Nicholas Torres, the lab is a safe space for social innovators to develop their ideas, learn about sustainable financial models, understand how to effectively communicate ideas to funders, and ultimately pitch their innovations. The lab brings together social innovators with business leaders and investors in a didactic setting to draw upon their experience, closing the gap in education and knowledge that impedes many of today’s most passionate social visionaries. This experience enables social entrepreneurs to marry their commitment and drive for social change with sustainable plans of action to bring their ideas to fruition within the social sector.

This white paper examines the efficacy of the lab, itself a social innovation, as it provides both budding and more seasoned social entrepreneurs with the guidance, mentorship, and resources to establish a successful social enterprise. The paper highlights both the mission and process of the lab experience, in addition to an intensive study conducted by independent evaluator Sean Evers, who concluded that the lab is successful in inspiring social enterprise. Furthermore, the paper emphasizes the many examples of successful outcomes based upon the lab experience, including ideas that are now fully functional programs, as well as existing programs and businesses that were able to redefine their goals and growth objectives as a result of the lab. This paper serves to show that, with social enterprise, the possibilities for social change are boundless. Furthermore, opportunities like the Social Innovations Lab enable social visionaries to gain the know-how, skillset and confidence to leave their entrepreneurial mark and change the world in the process.

Introduction

The United States is the entrepreneurial capital of the world and as such, has given birth to more innovations than any other nation, including in the areas of business, science, technology and the arts. Yet, when it comes to innovation within the social sector, such as health, human services and education, the U.S. has stagnated. In recent years and through public demand, the U.S. social sector has communicated the desire to improve its track record and is beginning to demand new social enterprise models that are cost effective, financially self-sustainable, adaptive to feedback and metrics and have clear outcome accountability measures with the potential for large-scale impact and systems change.

Despite the motivation to evolve the social sector and begin to solve large-scale social issues that plague the U.S., innovation is often disrupted by our regulatory systems resulting in the status quo. Social entrepreneurs and social enterprise have demonstrated solutions to many complex social challenges; however, only a few are able to succeed within an industry dominated by regulatory systems and funding constraints as compared with the private sector which is driven by consumer demand.

There are currently various models in the marketplace deployed to support the creation and development of social enterprises to combat large-scale social issues. These include, but are not limited to: Investments in proven models like the Greenlight Fund Strategy1; consultancies like the Bridgespan Group2 and Community Wealth Partners3 that develop great strategic action plans; and social incubators and accelerators like the Centre for Social Innovation4 that prepare entrepreneurs to develop their socially oriented business. While all the models have merit and have experienced success, each one is limited when using the criteria of cost (i.e. can the majority of nonprofits/government afford the model), longevity (i.e. does the product live beyond 6-12 months), and timing (does the product miss investment opportunities?).

The Social Innovations Lab model is a new and promising model to effectively launch social enterprises that have demonstrated better social impact outcomes into a regulated and heavily government funded industry. This white paper presents a detailed case study of Social Innovations Labs. A Social Innovations Lab is essentially a social enterprise leadership incubator that takes social entrepreneurs and change-makers through a social innovation simulation lab and process that teaches them how to think within the unique framework of social impact, design, financial, policy, and scaling best practices. Once these social entrepreneurs graduate from a social enterprise leadership incubator, they are deemed ready to interface with potential social investors. As a result of learning a new thought process while already an established passionate and motivated social change-maker, lab participants end up attracting social investors who launch them into a competitive and regulated social sector market.

Using consistent and reliable metrics and data, this white paper argues that the Social Innovations Labs model is an ideal model to effectively proliferate social enterprise when using the aforementioned criteria of cost, longevity, and timing. It argues that the primary driver toward success is about the leader and giving him/her and his/her team the appropriate skills and access to potential investors. By comparison, consulting is not affordable and results in very limited social enterprise launches. Furthermore, targeted investments, in addition to incubators/accelerators, are too costly and limited to a very selective group resulting in missed opportunities. The Social Innovations Labs model of investing in teaching already passionate and motivated social entrepreneurs more efficient thought processes and giving them specific social impact, design, financial, political, and scaling frameworks is inexpensive, lasts a lifetime, and results in more social investments.

Introducing the Social Innovations Lab Model

When asked, social sector-oriented leaders from the nonprofit, government and private sectors are increasingly drawn to funding social innovations that have a lasting impact in communities, create systems change, are financially self-sustainable, and have the potential to scale. A recent study revealed that when it comes to social innovation, social sector oriented nonprofit organizations in particular face challenges because innovation is not only about new products or services, but about changing the underlying beliefs and structures that can only come about from an enlightened workforce5.

Traditionally, staff in the nonprofit sector, whether young or seasoned, have not come with business, legal, or policy backgrounds and therefore do not have the knowledge base from which to bring social enterprise models to fruition6. At the same time, managers, worldwide, accept that good strategy is not the product of hours of careful research and modeling that lead to an inevitable and almost perfect conclusion7. Instead, it is the result of a simple and quite rough-and-ready process of thinking through what it would take to achieve what is wanted and then assessing whether it’s realistic to try.

The Social Innovations Lab (SIL) (www.socialinnovations.org) was created in 2012 as a result of the need within the broader community to create social innovations to combat social issues. SIL is a social sector program and business development incubator that was created for nonprofit and government professionals working in the broad social services sector, including, but not limited to, education, income, health and human services (basic needs) areas. Based in Philadelphia, SIL is co-founded by two education and health and human services social entrepreneurs, Nicholas Torres and Tine Hansen-Turton, as an outgrowth of the successful Philadelphia Social Innovations Journal (www.philasocialinnovations.org), the first regional publication in the nation dedicated to social innovators and innovations. Since its launch in 2009, the Journal has become a regional and national knowledge lab and thought leader for innovations, creating a common understanding of how to incubate social innovation and challenge social sector systems through dissemination of local best practices/solutions and the development of a new standard for creating social impact within the social sector.

Traditional business development incubators focus on social entrepreneurs seeking venture capital primarily to start and scale for-profit companies and drive innovations via the private market; however, the SIL focuses on social entrepreneur-minded professionals working or interested in working in government, nonprofit, or social enterprise sectors. Similar to their business colleagues, these professionals have a program or service idea they would like to explore further through the SIL. The overarching goal of the lab is to incubate new social sector delivery ideas via out-of-the-box thinking. This is achieved by building participants’ capacity to create innovative models to address health, human services, education and social issues, by teaching them the business and planning skills to which private-sector entrepreneurs typically have access through formal education and training. In addition, they are helped to develop the policy skills of which legislators/governmental officials typically have through formal education and experience. The SIL is an adaptive and generative orientation that teaches participants how to grapple with the complex social reality with which nonprofit organizations are challenged.

An underlying theme of the SIL is that sustainable and scalable social innovations must, at some point, tap into governmental funding. Therefore, the SIL focuses on creating social innovation programs and services that partner with and benefit the government, i.e. through cost savings. These innovations will generally be executed by a nonprofit and be financially supported by government, while keeping the core concept of consumer choice/demand. These social enterprises and innovations are intended to solve social problems, create social sector market opportunities, design new business models that support change and mobilize funding initially through philanthropic funding and later through government funding to sustain the innovation and accelerate impact. The overarching goal of the lab is to incubate new ideas, via out-of-the-box thinking, capacity building of professionals to create innovative models that address social issues, and teaching them the business and planning skills demonstrated by their for-profit counterparts.

As referenced previously in the SSIR study, young professionals, whether recent graduates or working in the nonprofit or government sectors, do not usually have the opportunity to learn or understand the process of innovation or social entrepreneurship. It is not a topic currently taught by most schools. Sadly, this educational void can serve as a detriment to their future careers and also puts the nonprofit industry at risk of being less of a player as the fourth sector evolves. The SIL is the only lab nationally of its kind to focus on social sector leaders who will pursue new ideas, products and services, working in teams to fine-tune and market test them, to create/adjust social impact measures and financially sustainable business models, to determine the feasibility of scaling the project, to conduct competitor analysis and finally, to create an execution plan that blends public policy and business practices. For social sector agencies, nonprofit agencies and their emerging or seasoned management to thrive, similarly to private sector entrepreneurs, there is a need to teach and expose them to the tools and resources that entrepreneurs pursuing private sector ventures need.

Social Innovations Lab Case Study

The Social Innovations Lab is a mix of classroom, laboratory, and accelerator structured in three core segments. The first segment provides participants with the opportunity to develop essential competencies around social innovation. The next allows participants to collaborate with each other, network with experienced professionals, and receive expert consultations to help test their ideas. The final segment encourages continued testing but is truly intended to accelerate the innovation toward investor presentations and project launch. Throughout the fifteen-week period, the lab very successfully adapts to the needs of participants. Instead of following a predetermined curriculum with fanatic obedience, the SIL is able to rapidly adjust based on ongoing feedback and periodic self-assessment surveys. Specifically, the core concepts of the SIL include:

- Idea Exploration Phase

- Idea Experimentation and Testing Phase

- Idea Plan Execution Phase

Idea Exploration:

Defining the Social Impact (the social change you want to make on the world) and Target Audience

- What is the issue and social problem that will be addressed?

- What is the social change you want to make?

- How will you measure this social change?

- What will success look like if you achieve the social change?

- Who is the target audience?

- Who is your customer?

- What shared traits or characteristics do your customers have?

- What is the proposed value to the consumer?

- Find potential customers as validation for your product and motivation for investors and funders

Opportunity and Innovation: Turning the desired Social Impact into a Social Innovation and Enterprise and Business

- What is your idea or Theory of Change to achieve your social impact goals?

- What is the product/service to be delivered?

- Sustaining versus Disruptive Innovation (Clayton Christensen Model)

- What is the idea/innovation leading toward a solution?

- What strategies have been developed/tried? What successes were achieved and why? What failures resulted and why?

- How is your idea or Theory of Change different?

- What needs to happen for this solution to work?

- What is the opportunity and timing for the idea/innovation?

- How do you know that your product/service has real value to the recipient (consumer)?

- What type of market testing (rapid validation) do you need to do before developing a market for your product/service?

Idea Experimentation and Testing:

Defining Social Entrepreneurship and Funding Models

- What is the difference between an entrepreneur and social entrepreneur?

- What are the attributes of being a social entrepreneur?

- Why is there a growing global need for social entrepreneurs?

- What makes a social entrepreneur?

- Attributes: Social Catalysts, Socially aware, Opportunity-seeking, Innovative and Resourceful

Creating a Sustainable Financial Model

Revenues

- What are the projected sustainable revenue sources? Who will pay for your product/service?

- Where to get start-up capital/funding? Who provides the required seed capital (government, angel investors, venture capitalists, foundations, loans, Social Impact Bonds)?

- What is the brand and why should they buy your service/product?

- What is my social return on investment that is attractive to investors/funders?

- SROI versus ROI

- Why analyze SROI?

- Overview of SROI Analytical Sequence/Calculating SROI: 1) Project Description; 2) Theory of Change: defining social issue to address, urgency and scale; 3) Identifying Stakeholders; 4) Input: sum investments made by all stakeholders to calculate total social value of your resources; 5) Activities: describe activities of all stakeholders who provide input; 5) Output: results of stakeholders’ activities; 6) Outcome, Impact and Attribution; 7) Indicators: determine variables to measure change; 8) Monetization; 9) Projections: calculating SROI for the long run; and 10) SROI ratio: impact divided by input

- Challenges to procuring social investments

Expenses

- What is the product development cost?

- Identifying start-up, fixed and variable costs

- What are ongoing needs: money, people, technology and activities required on a daily or monthly basis to sustain your business. Ongoing costs are the expenses you must keep paying to stay in business, such as rent and salaries.

Financial Modeling

- What is your break-even point, and how long it will take to get there? When is the model financially self-sustaining?

Creating a New Social Sector Market

- Is there an existing market for the innovation?

- What is the demand? Do you have enough supply?

- What is the marketing strategy and outlets?

- Marketing defined: building a relationship with your customer, and getting them to know and trust you

- Sales: how will you get, keep and increase your customers over time? What is your price, and how will you sell your product or service?

- How to spread your message

- Fine-tuning the message and marketing based upon rapid validation

Idea Execution Plan:

Defining an Organizational Partnership, Leadership, and Team Strategy

- Who are the closest potential competitors?

- Who/What is the competition? How are you different?

- Analyze the most competitive alternative

- How have similar initiatives marketed themselves? Have they succeeded?

- Who are my organizational partners? What are the legal and financial implications for a collaboration or legal/financial partnership? How do I build partnerships and what partnership models do I use? (Collaborations, Joint Ventures, Affiliations, Mergers)

- Who am I as the social entrepreneur and how am I portrayed to potential costumers and investors? What are my core competencies?

- Who are my advisors, support network, colleagues or prospective board members?

- Who are my management team and partners? Do they have the skill set to deliver (leadership team, management depth and skills/expertise to execute)?

- How ready is your organization/team/partnerships to deliver and scale?

Scaling and/or End Game Strategy

- How big do I want to grow?

- Where do I start and how long will it take me to scale?

- Can the model be scaled via a change in national, state, or local policy, consumer demand, and/or replication of the model?

- Does scaling occur within the organization, through partnerships and affiliations, or through open source sharing?

- Scale via policy, consumer demand and replication

- Scaling from within an organization, starting a new organization or developing partnerships

- What is my end game and/or exit strategy?

Conducting Social/Policy Analysis

- Are there policies in place that will impact the design, reception or scale?

- What are the social/political barriers and/or threats?

- Address the Inevitable Socio-politics: The lack of consistent administration and governance can complicate or even derail potential innovations due to problems, securing permits, or accessing potential stakeholders

- Addressing socio-politics: 1) Identify and categorize stakeholders (allies, opponents, needed, indifferents), and 2) Strategy Development (identify response and create diagram to map out options/solutions for each stakeholder)

Strategic Action Plan/Social Business Plan: Putting it all together

- What is a Business Plan?

- What is a Strategic Action Plan?

- What format is best used for what audience (internal, external funders/investors, external consumers/recipients)

SIL Lab Sessions:

Each lab session usually involves one or two external speakers/experts online or in the lab to provide perspective on various aspects of entrepreneurship and/or social impact. These individuals came from a variety of backgrounds including working within the public sector, the private sector, the nonprofit sector, or some combination of them all – including the social enterprise sector. The varied perspectives give participants an opportunity to investigate various models and collaborate with individuals who have succeeded in developing social innovations for a plethora of societal challenges. The majority of these expert advisors give examples of designing business models, developing financial statements, and building leadership teams. Each discusses social innovation within the context of their specific area of expertise, demonstrating that innovation can occur in any sector and often between sectors.

Experts who come to the lab in person often stay after their talk to directly consult with the participants. In the first five weeks of the course, this is usually more informal, where groups of participants have the opportunity to meet and consult with expert advisors, facilitators, or other participants. In the latter part of the lab, participants have the opportunity to pitch their ideas to the expert lecturers sitting in as panelists after providing their lectures. Participants have five minutes to present their ideas and receive feedback. The commentary is extensive, honest, and always constructive. Each week, participants will pitch to another panel of experts and use the information from the previous panels to improve their pitch. Innovators not only receive senses of validation and personal efficacy, but also control over their learning environment.

At the core of the lab’s delivery strategy are two facilitators, each with strong backgrounds in social entrepreneurship, nonprofit management, executive leadership, and academia. Each has extensive networks that contribute to the lectures, offering expert consulting and networking opportunities for aspiring social entrepreneurs. Beyond their backgrounds, each brings a unique perspective in terms of how to approach different social problems. Their perspectives are coupled with speakers who take more of a systems and design thinking approach, providing a third dimension to developing innovative approaches to impervious problems. Each discusses their unique approach from the outset, signaling to participants that they will have the opportunity to fully consider the range of issues they may face and the wide array of approaches they can take to address them. The facilitators are connectors playing the critical role of linking people, ideas, money and power to enable entrepreneurs, thinkers, creators, and designers in order to launch successful social innovations.

Although the SIL incorporates the foundational elements of most business acceleration services, it generalizes them to avoid predetermining the legal status of the project at the onset of the program. The innovation can generate profit, surplus revenue, or a budgetary surplus and operate in the private, nonprofit or public sectors. Innovations can grow into independent entities or projects within existing organizations. The core objective is that the social innovations have the best opportunity to launch and deliver sustained impact. Cohorts of participants with untested innovations are the core audience of the lab. Individual participants can also apply and participate, but are encouraged to identify partners to bring to the lab. This encouragement comes not only from lab facilitators, but also from visiting consultants and expert lecturers with decades of experience in entrepreneurship.

Now in its sixth cohort, SIL participants/graduates have generally sought to address a range of societal needs. Participants develop innovations in the areas of early childhood education to k-14 education and college, health and human services, community development, youth services, micro and small enterprise development, among others. Most participants are looking to create independent organizations, while a few are usually looking to test out innovations that could be implemented by existing enterprises, nonprofits, or government agencies. The diversity of projects and development stages bring immense value to the lab.

Defining Successful Outcomes - An Independent Study

The Philadelphia-based Social Innovations Lab contracted an independent evaluator, Sean Evers, to test the effectiveness of the Social Innovations Lab model. Below represents a summary of his conclusions:

The SIL model states that the goal of the Lab is to “increase the chances that the strongest ideas of social innovators will take root, attract the needed capital, and ultimately have a significant social impact regionally, nationally, and internationally”. The SIL intends to deliver these outcomes by fine-tuning innovation through research and consultation, testing the innovation in the real world, and seeding the innovation with real investors. The model also defines key attributes of the lab environment as: cross-sector, low-risk, high-return, data-rich, and cooperative. The findings of this study are consistent with most of the intended outcomes stated in the model. The SIL enables participants to use best practices research and consulting to fine-tune innovations, pilot test models in both laboratory and real world environments, and pitch their ideas to real investors. The lab environment provides cross-sector, low-risk, and cooperative elements to the benefit of all participants.

Furthermore, participants bring a variety of backgrounds and are encouraged to impart their knowledge while learning from their peers. This greatly enriches the peer-to-peer learning environment and allows participants to adapt their projects, consider new ideas, and even partner together on projects with similar objectives. Facilitators encourage discussion and collaboration among different lab participants, giving them control over the learning process while creating an environment for social referential comparison to encourage goal setting and improve motivation. The facilitators encourage this open learning environment while still ensuring participants have adequate access to knowledge and networking resources.

SIL Collaboration:

At the core of matching the ideas, innovators, and delivery mechanisms is establishing the platform where ideas can cross-pollinate to develop viable solutions. These platforms service the public, private and nonprofit sectors as safe environments to explore, experiment and execute new ideas in the social innovation space. The SIL attracts individuals and groups from diverse academic backgrounds, skill-sets and interests and provides them the opportunity to collaborate together as they work on distinct projects. This cross-sector cooperation is fundamental to the lab.

Exploration: Establishing the Conceptual Base:

In the first five weeks of the lab, participants explore fundamental concepts in social innovation. Innovators use this conceptual knowledge to better define their problem, their target populations, the resources necessary to implement solutions, and the possible avenues to implementation. The goal is to transform an idea into an innovation by taking a creative social sector solution and making it meaningful and concrete, in the form of goods or services, and preferably with some market value. This transformation is facilitated through a Socratic learning environment. Participants are provided the tools to learn key concepts but do so by investigating their own solutions, inquiring about various conceptual ideas, and developing their own base of social innovations knowledge relevant to their project. The role of the facilitators is not to transmit codified knowledge, but to support the self-directed learning process.

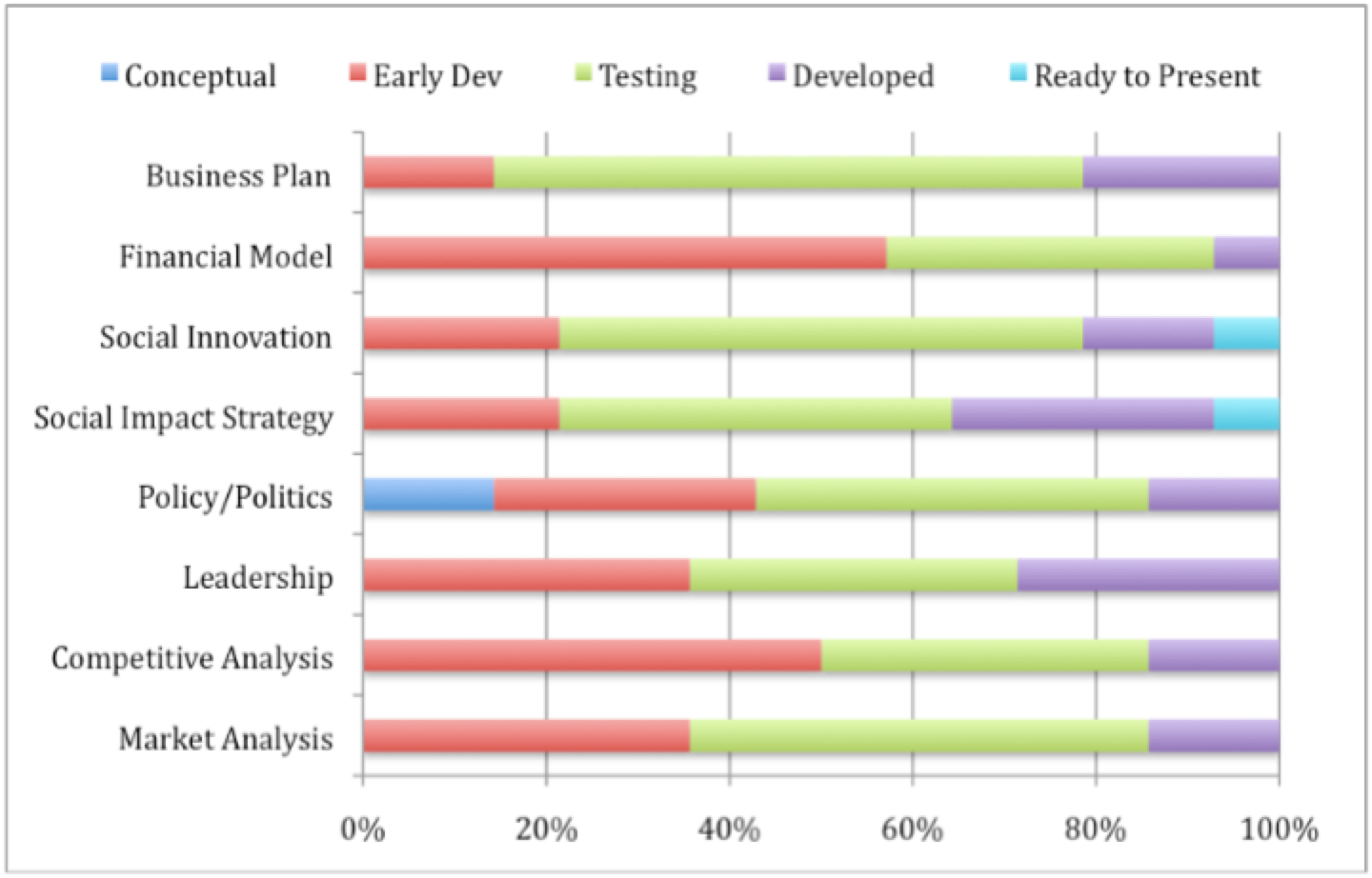

The core concepts emphasized in the first five weeks of the course were social innovation, business plans, financial models, social impact models, market analysis, competitive analysis, policy/political analysis, and leadership. These concepts were identified as the fundamental components for turning an innovation into a scalable solution. None of the concepts were directly ‘taught’, rather discussed as important components of innovation development and emphasized by numerous outside consultants.

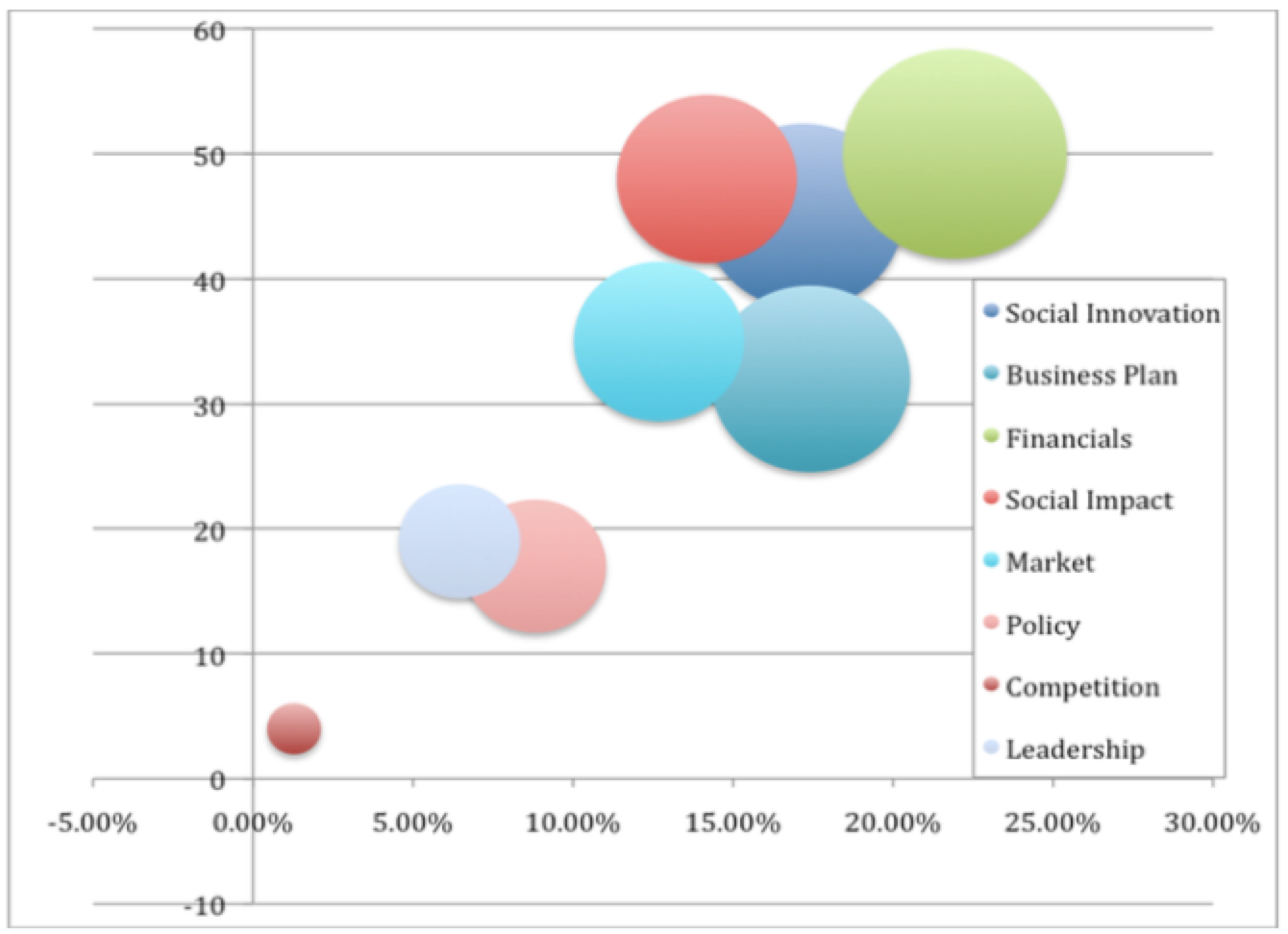

Figure 1 shows the proportion each topic was discussed relative to the other key themes on the horizontal axis. The vertical axis represents the number of times a key word related to that subject was used, and the size of the bubble indicates the total number of instances this topic was mentioned:

Figure 1: Proportion of Discussion Topics (Week 1 to Week 5)

Social innovation, business plans, financial models, social impact and market analysis were the most commonly discussed topics during the first five weeks of the lab. It is important to recognize the clear overlaps between these themes, and that multiple topics were often discussed in conjunction. Some examples include policy and political analysis, which tie into social impact strategy and social innovation at very important levels. Competitive analysis is part of business planning, market analysis, and many other core components. What is notable about this graph is the heavy clustering of core themes, showing the level and density of the discussion between participants, facilitators and lecturers, and overall the inquisitiveness of participants.

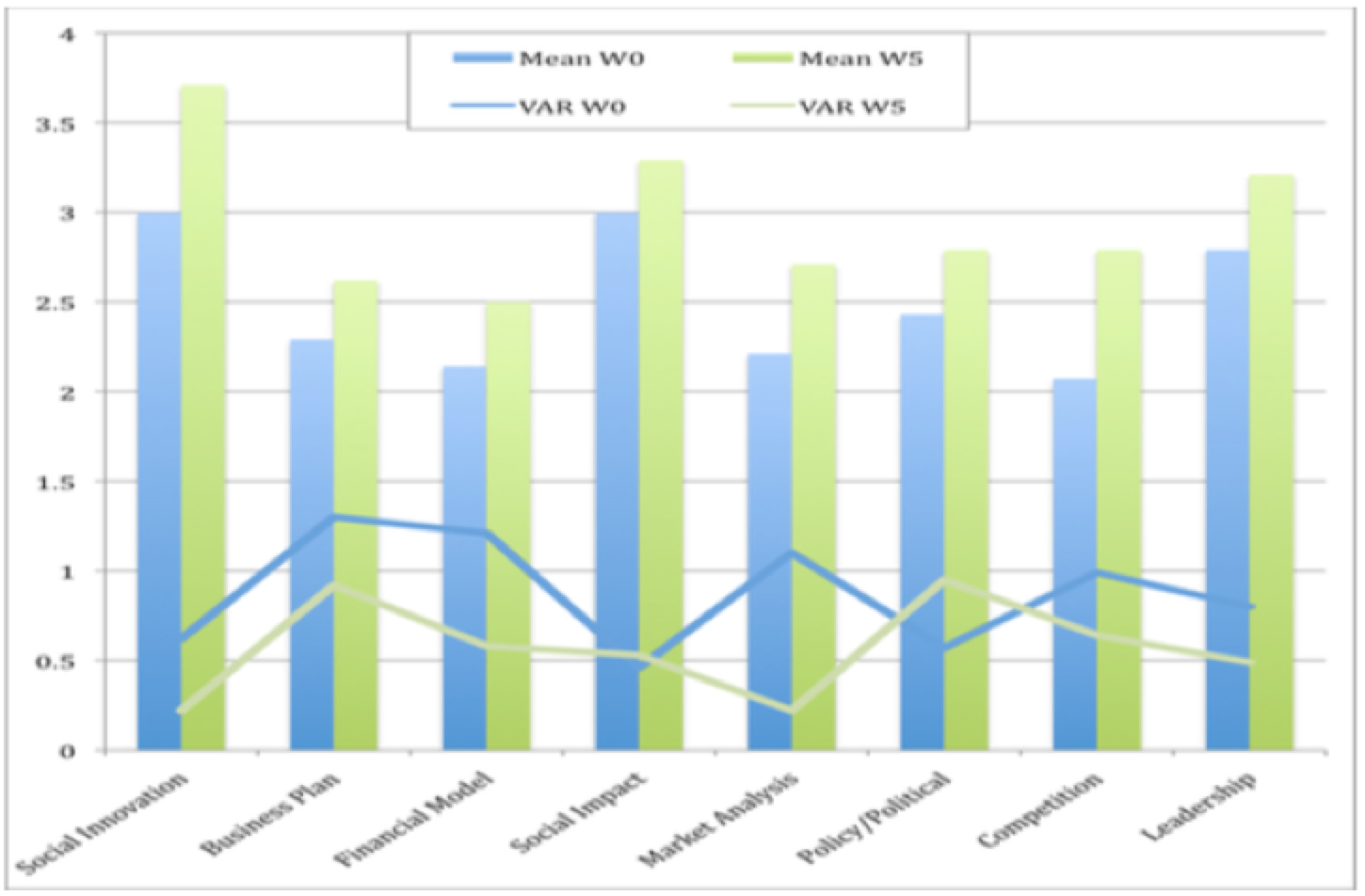

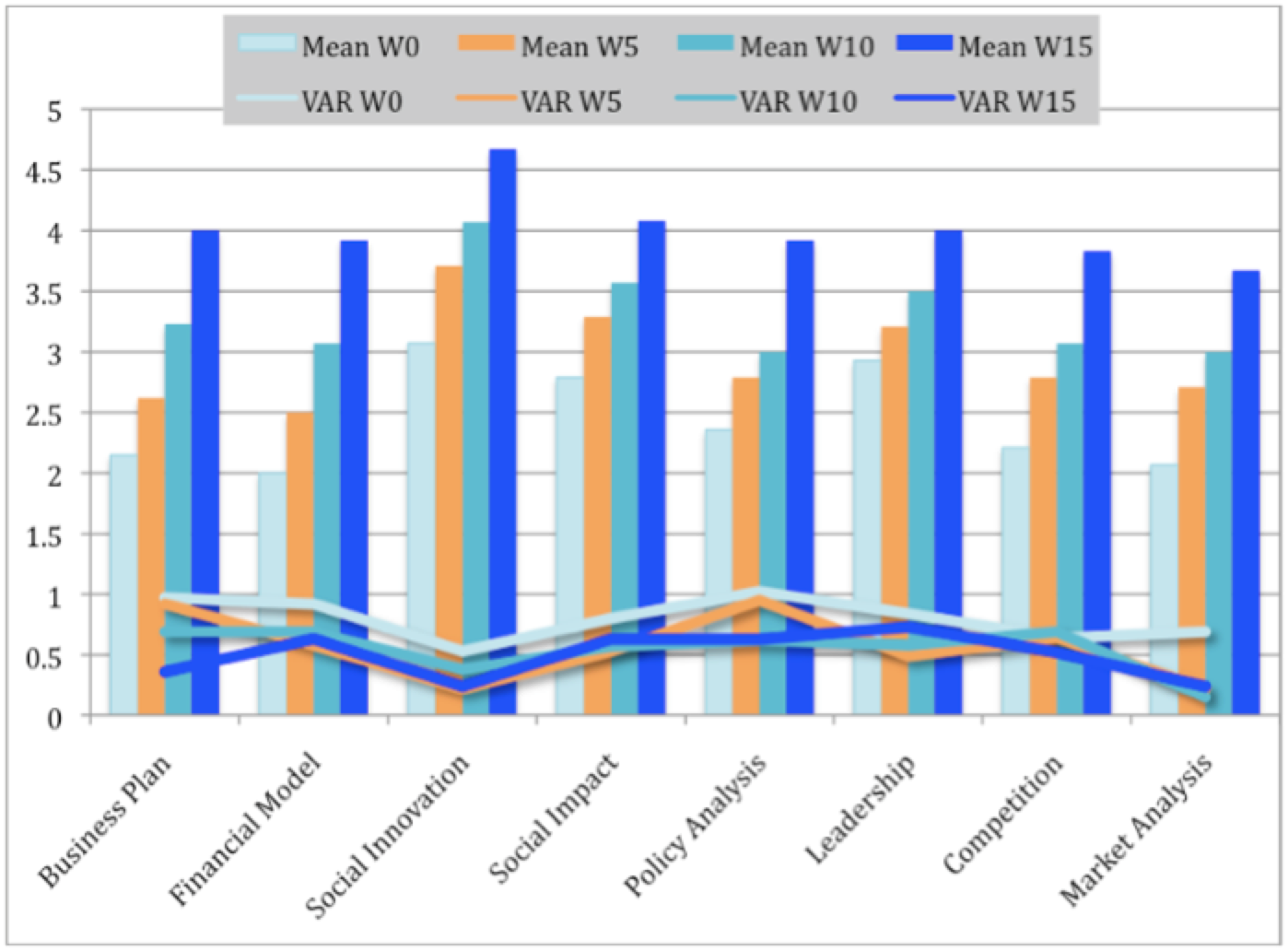

To supplement the ethnographic note taking, self-assessment surveys are administered at the end of each five-week block. This provides participants with the opportunity to evaluate their perceived progress through the lab. Along with monitoring overall progress, the surveys provided both a tool for participants to monitor their own performance and an incentive to set goals, which can “enlist evaluative self-reactions that mobilize effort toward goal attainment8”. Reviewing survey results demonstrated successes and shortcomings, and allowed the facilitators to adapt their approach to improve outcomes for the lab as a whole. Figure 2 illustrates the responses from the first survey, indicating a mean increase in the self-perceived level of understanding of the core social innovations concepts from the point of entering the PSIL (W0) to completion of the first five week (W5):

Figure 2: Self-Perceived Understanding of Core Concepts (W0-W5)

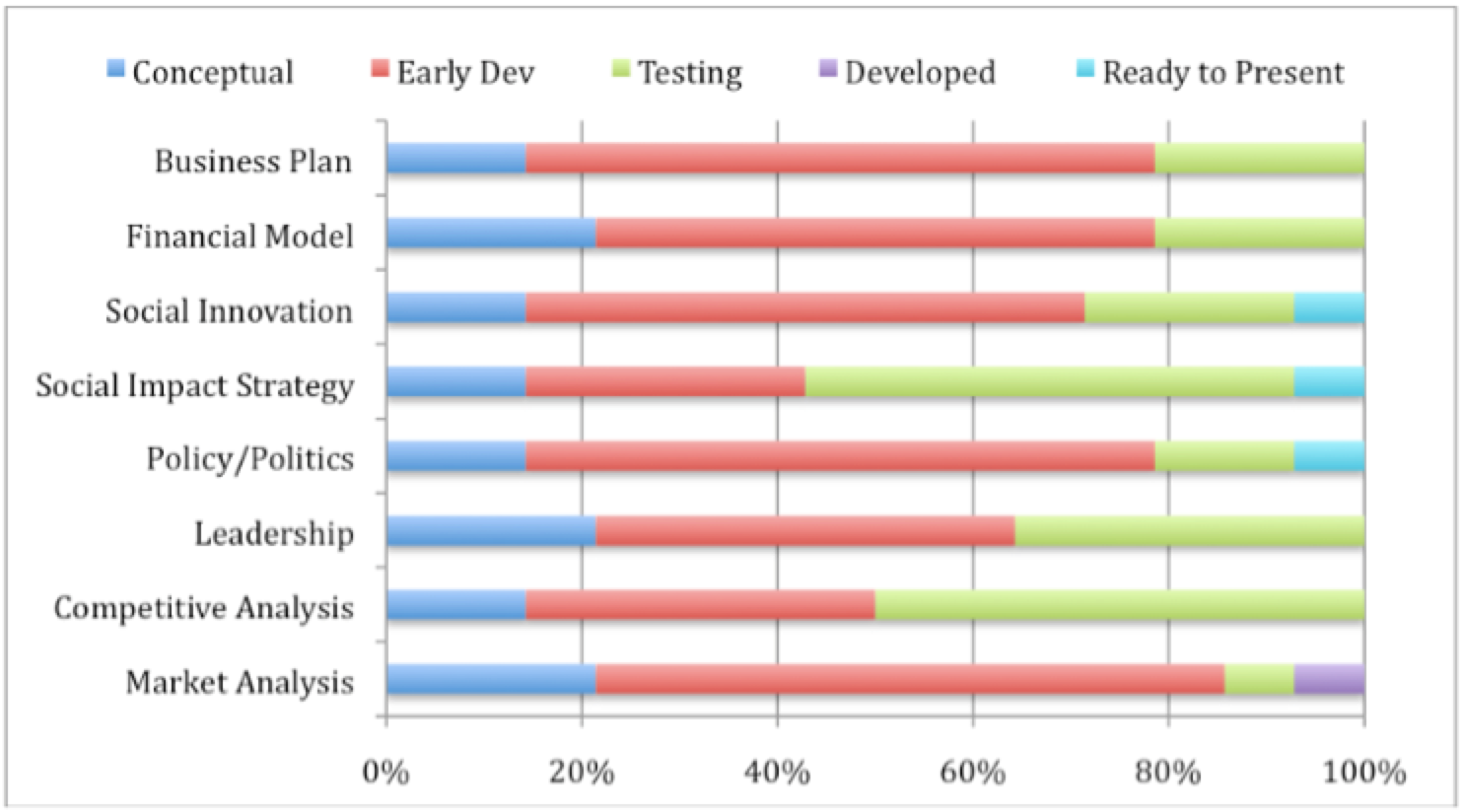

Although there appears to be a loose correlation between the topics discussed and the level of self-perceived conceptual knowledge, this is more illustrative than conclusive. In areas where the discussion level is high but the conceptual knowledge is low, participants were usually asking more questions on the topic, facilitating further discussion and increasing the proportional representation of a topic in Figure 1. The graphic representation of notes also fails to capture all direct consultations with participants. Evidence of lower understanding is more apparent when we look at the gap in applying some concepts to their actual innovations. After the first five weeks, most lab participants still considered different stages of their innovations, corresponding to the core competencies above, in the “Early Development” stage:

Figure 3: Self-Perceived Innovation Stage after Week 5

The strongest component areas, based on being “Ready for Testing”, were actually the Social Impact Strategy and the Competitive Analysis. This is interesting because Competitive Analysis was the lowest mean level of understanding in the core competency questions (Figure 2) and the least discussed (Figure 1), while Financial Model had the lowest development stage (Figure 3) and third lowest core competency level (Figure 2), despite being the most frequently discussed (Figure 1). This indicates that Competitive Analysis was less well understood and less frequently discussed in the first five weeks, thus not as highly prioritized by participants; however, the topic of competition is more appropriately discussed in direct consultations, especially given the range of social issues the participants were seeking to address. Many were also seeking to establish collaborative programs, and others were breaking into entirely new segments. As we will see in the next section, the survey results provided the facilitators better knowledge of how well participants were performing and transitively the lab itself. This allowed for adjustments to the subsequent sessions in order to meet both participant and lab goals9.

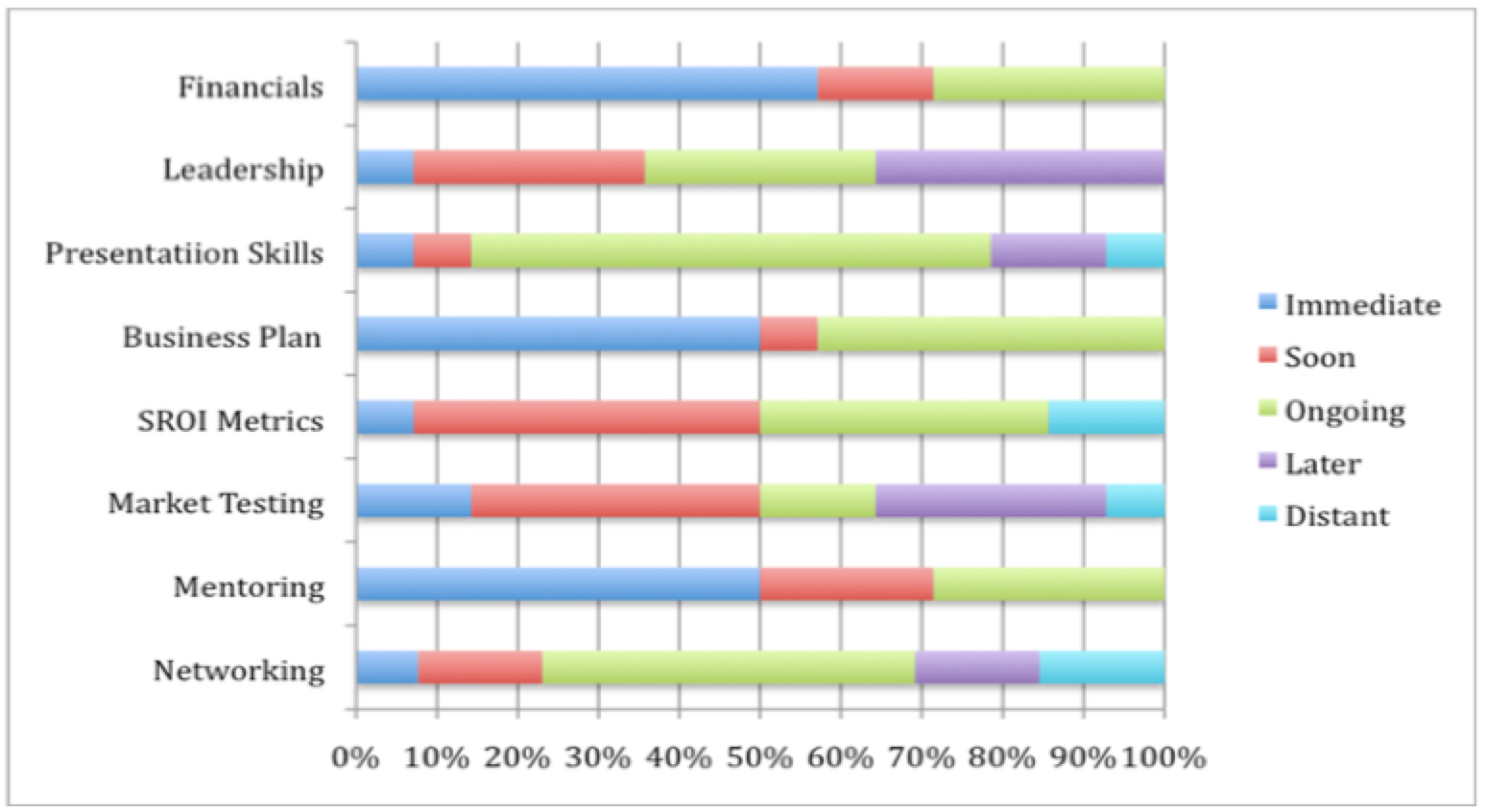

A third question set demonstrates the level of time sensitivity each participant experienced relative to different stages of their innovation:

Figure 4: Self-Perceived Innovation Needs after Week 5

These responses indicate that participants sought more mentoring and consulting after the first block, primarily in the areas of business plan and financial model development, which matches the density of thematic discussion on these topics (Figure 1). These topics also encompass many of the other social innovation components. The relationships between the conceptual knowledge, innovation stage and time-sensitivity of needs allowed facilitators to recognize which areas needed additional attention in the next block of the course. In exploring social innovation concepts and the needs of their projects, participants developed a better understanding of these fundamental components through the lens of their innovation. The use of self-referential comparisons through surveys demonstrated the need to increase the application of this knowledge to their projects through experimentation. Upon completion of the first block, participants were ready to build out their business plans and begin applying their knowledge of social innovation.

Experimentation- Defining the Solution:

“Experimentation platforms give organizations a neutral environment for building and testing solutions in stimulated or ‘near-real-world’ contexts.” 10

The experimentation platform is a core strength of the SIL. By the conclusion of the first five-week block, several participants had modified their innovations to more practical delivery models based on the conceptual knowledge gained in the first part of the course. Direct consultation with established social innovators, investors, foundations and academics also gave participants the opportunity to validate their ideas and gain feedback on how to improve the approach. Outside of the lab, participants were encouraged to test their market by interviewing potential customers, talking to potential funders, and vetting their idea with their potential target market and ‘non-consumers’. Identifying new customers or beneficiaries has been identified as a key strategy for successful business innovation11, as well as social innovation12. This experimentation process allows participants to test the viability of their models both inside and outside of the lab. The immediate feedback inside the lab often encouraged participants to go out and test their ideas directly with their expected customers or beneficiaries.

At the end of week ten (W10) another survey is usually conducted. The second survey asks participants to reassess their level of understanding from when they entered the PSIL (W0) and after week five (W5), in addition to assessing their self-perceived knowledge as of week ten (W10). Across the board the mean understanding for each concept increased over the ten-week period. This includes concepts such as Competitive Analysis and Financials, where lab facilitators used the results from the previous survey to increase access to resources on these core themes:

Figure 5: Self Assessed Understanding of Core Concepts (Week 0, Week 5, Week 10)

The variance also demonstrates a convergence in the level of understanding for most concepts, with the exception of financial model and leadership where there was a large convergence between W0 and W5, then a divergence between W5 and W10. This survey was taken prior to a speaker on leadership in Week 11, which explains some of the divergence for this concept. For the financial model, the responses indicate that some participants were still challenged in developing their financials (over half still consider this in the ‘Early Development’ stage):

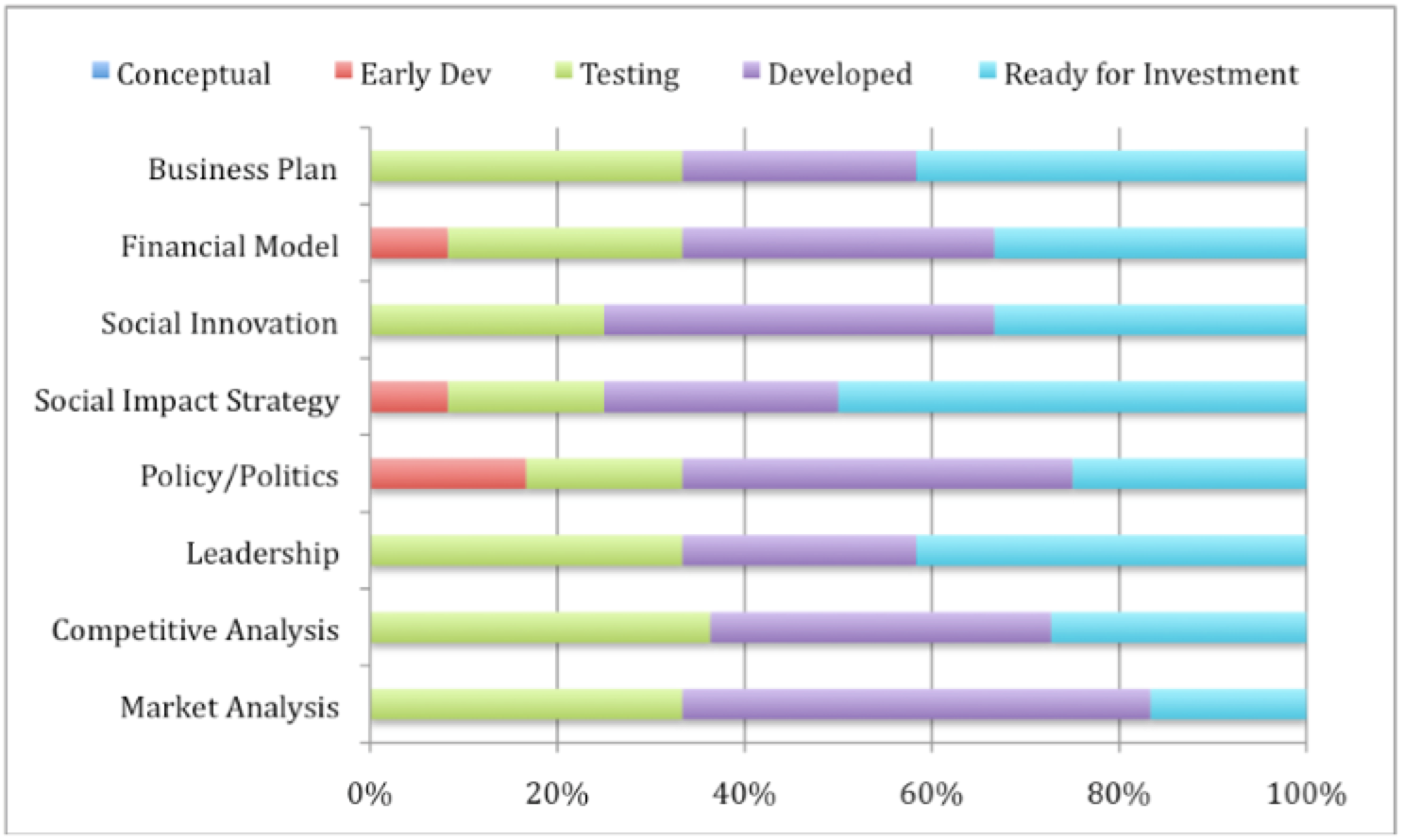

Figure 6: Self-Perceived Innovation Stage After Week 10

Overall, the growth in understanding core concepts (Figure 5) and mean increases in innovation development stages (Figure 6) demonstrates the results of applying conceptual knowledge to innovations. The increased core concept knowledge was supplemented by a positive shift in the innovation stage of most participants from ‘Early Development’ to ‘Testing’ (Figure 6). These increases are partially a result of the facilitator response to the first survey. The adaptation of certain thematic elements to meet the needs of participants was obvious. This sent a strong signal. It gave participants a better sense of control over their learning environment suggesting “when people believe the environment is controllable on matters of importance to them, they are motivated to exercise fully their personal efficacy, which enhances the likelihood of success.13”

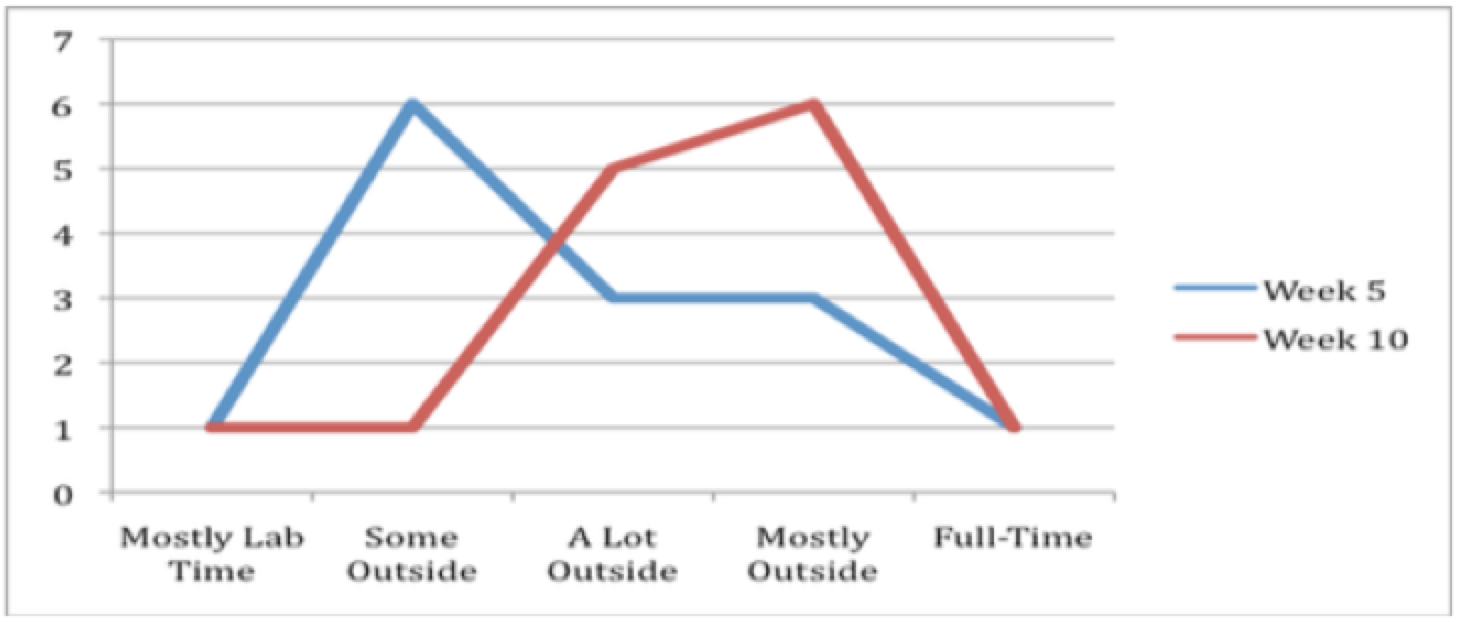

These self-perceived improvements are an important indicator for how well the projects will move forward. The increasing level of work outside of the lab reinforces this notion:

Figure 7: Self-Reported Workload Inside and Outside Lab Sessions

We see a clear shift in self-reported workload from half of the participants indicating that most work was done within the lab during the first five weeks, to most (86%) reporting that the majority of their work was performed outside of the lab. The summary of these survey results is an increased probability of successful outcomes for each of the lab participants, and hence for the lab itself. The form and level of this success is not yet clear, but the motivational elements demonstrate that all participants are likely to deliver impact at some level.

Experimentation is critical to social innovation, where few ideas emerge fully formed and innovators often try things out and quickly adjust based on this experience.14 The cost of implementing a project prior to fully testing can be enormous, especially if the result is negative and results in unanticipated negative externalities15. The SIL offers innovators and organizations an adaptable and safe environment to experiment prior to implementation.

Execution: Presenting and Preparing for Launch:

The execution phase begins with the final block of the SIL, but the outcomes have not been clearly defined. Based on the lab syllabus, the output of the lab is “to increase the chances that the strongest ideas of Social Innovators will take root, attract the needed capital, and ultimately have a significant social impact”. There are a number of situations where participating social entrepreneurs will go on to launch their models, collaborate with others participants in launching an innovation, or take part in scaling existing solutions. One benefit of having several projects in a more advanced state earlier on in the lab is the social referential comparison16, providing strong motivation for other participants to accelerate their models toward execution. But there is also a situation where a curious social innovator will be confident that social entrepreneurship is not their path. They have still contributed to the field, as even failed ideas often point the way to ideas that will succeed17. All of these outcomes should be considered successes, as they help to direct human resources toward the right path in the field of social innovation, whether they encourage the development of social entrepreneurs or social change agents within organizations, all are equipped with powerful tools to make a positive impact.

The final survey responses show signs of each of these scenarios. The overall increase in self-perceived social innovation knowledge, across all core concepts, was clearly demonstrated through the SIL:

Figure 8: Self-Perceived Understanding of Core Concepts (End of PSIL)

The application of this knowledge has also grown, and the self-assessments of innovation stages reflect this as well.

Figure 9: Self-Perceived Innovation Stage after Week 15

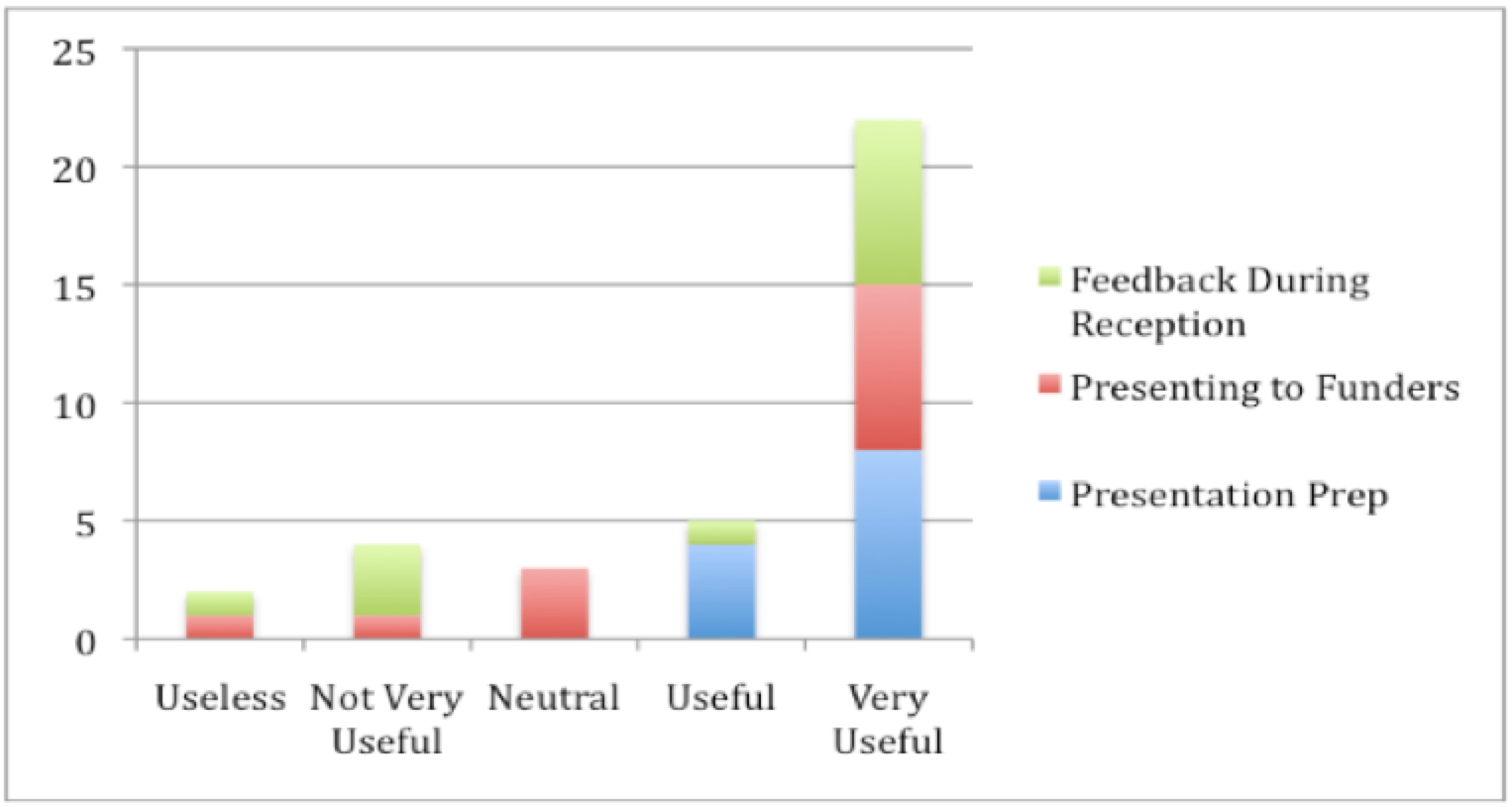

These results show clear benefits of the lab. It also appears that most participants found the final pitch and reception useful:

Figure 10: Value of Final Pith, Including Preparation and Reception

There is clearly a range of perspectives on the networking benefits, and this was seen in the assessment of networks established during or after the PSIL.

Although facilitators make every effort for participants to succeed, the outcome of the individual or cohort’s innovations is entirely up to the innovator. The lab serves as a source of knowledge, feedback, networking and general resources but the level of achievement ultimately depends on the participant’s level of effort. This includes the drive and ability to establish and strengthen network linkages when resources are available.

SIL Outcomes- Different Forms of Success:

Based on the observations and assessment of this case study, there are four possible outcomes for SIL participants. All accelerators share the goal of launching successful projects, but the three alternative outcomes make the SIL a unique environment for risk mitigation. It also increases the likelihood of successful innovations reaching scale.

Success as Innovation Launch

The core objective of the SIL is to launch successful innovations capable of scale. But the facilitators do not force any idea through the lab and into the community. Instead, the SIL allows participants to truly test out ideas in an open and collaborative environment, building core skills while also receiving honest feedback and allowing for innovators to adapt or change their model to increase the likelihood of success.

Success as Failure to Launch

This seems counter-intuitive until considering the laboratory component of the SIL. Labs are intended to allow for testing and failure, while mitigating the negative impact of failure. In this environment participants have reduced personal, professional, organizational and financial risk. Society is protected from ideas that cause unintended damage. The failure of an idea is not always the end of an innovation18; rather it allows the participant to redirect energies to projects with similar objectives.

Success as Collaboration

SIL applicants are expected to bring an innovative idea to the lab, but it is entirely possible that two participants will have very similar objectives. Participants are repeatedly encouraged to partner either within the lab or identify outside partners in order to increase their chances of success. In response to the final survey, one participant commented that by “Observing the other participants, the value of having a full time partner for this type of project became very obvious.” Several participants identified similar goals and partnered on projects. Collaboration can also occur between two different projects to ensure mutually beneficial outcomes. In the inaugural SIL Session, one participant’s first customer was another project in the lab. Another participant collaborated with a facilitator to implement a live test environment. Two other participants collaborated on an innovation that had already launched, leading to a fourth successful outcome.

Success as Resource Matching

A major strength of the SIL is the networks of its facilitators, advisors, and sponsors. It also attracts highly talented and motivated individuals seeking to have positive social impact. But if their innovation is not ready to launch, and no projects within the lab are of interest, there are a number of external projects seeking talented and motivated individuals to help take projects to scale. Another way to view this outcome is the PSIL as a social innovation venture lab. The SIL is bringing together a variety of resources and testing ideas, ultimately generating change by growing and diffusing social ventures19.). In attracting social innovators with audacious ideas, there will inevitably be participants that realize their ideas are not feasible at this time. The SIL provides them with an opportunity to contribute to innovations with existing resources already in the execution phase. The lab provides the unique ability to match the appropriate talent with financially sustainable projects. This is a unique feature of the SIL that provides a mixture of Social Innovation R&D and Social Innovator Talent Acquisition, testing scalable solutions with the support of ambitious and skilled individuals.

The SIL will produce each of these outcomes, meaning the benefits of the lab vary by the participant. The adaptive nature of the lab increases the potential for success. Establishing predefined outcomes limits the ability of the participants to maximize their potential for positive social impact. If each were pushed to execute on the exact ideas that they had walking in the door, at least a quarter of the lab would have ‘failed’ and perhaps been discouraged from pursuing opportunities in social innovation. Instead, the SIL environment allowed each to approach ideas based on their perceptions and expressions about the world as they see it, providing the intrinsic quality and essence of their motivation20. The entire lab cohort will succeed in developing further knowledge about the social innovation space through their own lens, and continue the push toward delivering blended value across sectors. The adaptability allowed participants to modify their approaches to more successful outcomes, or postpone their ideas and have an opportunity to gain experience executing on a more developed concept. Motivated individuals with overly ambitious ideas are not discouraged, but provided with the opportunity to participate on successful projects.

In this instance, the SIL also works as an R&D Lab for ideas as well as individuals. It attracts audacious ideas and ambitious people. The SIL helps converge innovative thinking and social ambition to scalable solutions that can address social problems by serving underdeveloped markets21. It does so by not only cultivating existing innovations, but enabling motivated change agents to pursue social impact opportunities. One can imagine the number of talented individuals that stop pursuing their ambitions for social change and settle for a more conventional career alternative. The SIL differentiates from this traditional path. It offers ambitious individuals the opportunity to pursue a social innovation crafted by experienced social entrepreneurs, implemented through their existing networks, and demonstrating the potential of scalable social models.

Conclusion: SIL as a Social Sector Evolution Best Practice

“Partners use the exploration platforms to define what the problem is; they use experimentation platforms to test possible solutions to the problem; and they use execution platforms to disseminate the solutions.” 22

To date, over 100 lab teams have completed the Social Innovations Lab process. At the conclusion of the lab, ideas are in various stages of securing funding or being piloted by turning into social enterprises that officially incorporated; incorporating; incubating in nonprofit agencies; connecting to fiscal agents and are pursuing funding opportunities; and others continue to be in an incubation stage. Over 60 jobs have been created and over 6 Million have been leveraged in private, public, and philanthropic support.

Overview of Successful Social Innovations Lab Results

Innovations at Work: Results and Outcomes of the Social Innovations Lab

The following examples underscore the successful social ventures that have come about as a result of the Social Innovations Lab and indicate how proliferating similar labs across the country can generate a new wave of social entrepreneurship as a solution to complex, social issues.

Example 1: Nurse Practitioner School Health Clinics:

A team of nurses developed a new type of school health clinic model. These school health clinics are now in fourteen charter schools in Philadelphia as a result of the lab and offer an innovative alternative to augment traditional school nursing. The clinics are staffed by nurse practitioners (NPs), who are valuable in their ability to provide primary care and preventive care—as well as traditional school nursing services—to children within the walls of school buildings where they spend the majority of their time. The nurses are on-site advanced practice registered nurse practitioners who are able to render a diagnosis, write prescriptions, develop and implement treatment plans, monitor chronic conditions, coordinate care with students’ medical homes, assess and treat acute injuries and illness and fulfill all of the school health reporting requirements such as state-mandated screenings, (e.g., Body Mass Index, hearing, vision, and scoliosis for crucial early interventions). The NPs ensure that students are connected to a medical home and work to coordinate care with students’ primary-care physicians through this innovative and collaborative approach to health-care delivery for high-risk children. Since implementation of the school health clinic model, the number of visits by students to the emergency room—a principal reason for absence in school—has dropped to zero for the school year, similarly unexcused absences have decreased from 129 in the school year to 2 in the school year, and overall attendance increased.

Example 2: Creating College Access for All:

Through a partnership between Colleges/Universities and High Schools, a Social Innovations Lab team is scaling a new high school to college access, affordability and completion model. The model establishes satellite or blended learning sites as extensions of high schools, thereby ensuring that college is accessible; negotiating reduced college tuition costs to just above what low income students can leverage in financial aid grants, thus ensuring college is affordable; and graduating 90% of entering students through the delivery of a small cohort boutique model, ensuring the college is accountable. The program through its college partners educates, trains, and places qualified individuals to meet employers’ changing workforce needs, including allied health, which is a feeder to nursing. The program works in close partnership with employers to assure that graduates have the real world competencies they need to be successful in the workforce. Through a supportive learning environment and personalized attention, the College Access for All program transforms lives by building a path to sustainable careers and economic independence. To date there has been a 90 retention rate and 90% of graduating students with an Associated Degree are placed in jobs starting at $35k with full benefits.

Example 3: Teaching Literacy and Learning Challenged Children through Gaming:

A state-wide cyber charter school that focuses on teaching children with special needs and their special education teachers went through the Social Innovations Lab and worked in partnership with the Philadelphia Game Lab to develop an educational early literacy cloud-based game, EdPlusReader™. This game replicates a successful evidence-based early literacy model to a cloud-based structure that can be disseminated to students with dyslexia and reading-based learning challenges and their parents, teachers, and tutors globally. The purpose is to ensure that learning disabled and other children acquire the early literacy reading foundations to be successful in school and life.

Examples 4-7:

4) A public private partnership was established to create a private high quality daycare, using public and private dollars to subsidize 30% of the slots to be for low-income parents. The team secured start-up funds and has been approached by a large local funder to scale. The daycare will create 15 new jobs; 5) Clarifi College, which is an online and in-person low cost model to assist families and individuals with identifying affordable colleges, is up and running as a fee-for-service model. It has created 3 jobs; 6) Childware, which is a software solution to assist low income daycare providers manage their operations better and bill the state, is up and running and expanding as a result of the lab. It has created 3 jobs; 7) Students Run Philadelphia partnered with Students Run Los Angeles to scale their programs together nationally and creating a national platform for running mentoring programs. It will create 5 jobs.

Closing Thoughts on Social Innovations Labs

The social sector in the United States, through public demand, is beginning to seek new social enterprise models that are cost effective, financially self-sustainable, adaptive to feedback and metrics and have clear outcome accountability measures with the potential for large-scale impact and systems change. Despite the motivation to evolve the social sector and begin to solve large-scale social issues that plague the U.S. through social enterprise, many social entrepreneurs lack the training and resources to see their ideas through to sustainability in a highly regulated and competitive marketplace, resulting in the status quo.

The current models in the marketplace deployed to support the creation of social enterprises, although each with merit, are limited when using the criteria of cost, longevity, and timing. The Social Innovations Lab in Philadelphia, PA, has emerged as a means to equip social entrepreneurs with the tools and resources to successfully effect social change. The Social Innovations Lab model is an enterprise leadership incubator that takes existing passionate and motivated social change-makers through a social innovation simulation lab. This process teaches them how to think within the unique combination of social impact, design, financial, policy, and scaling, empowering them to attract social investors and launch them into the social sector market.

A Social Innovations Lab model is an effective model when using the aforementioned criteria of cost, longevity, and timing. A 2012 independent study by a contracted evaluator underscored the proven efficacy of the lab as a model to inspire social innovation and empower social entrepreneurs. The Social Innovations Labs model of investing in and teaching already passionate and motivated social visionaries new thought frameworks is inexpensive, lasts a lifetime, and results in more social investments. This model can be easily replicated throughout the United States and around the globe. By supplying social entrepreneurs with the appropriate guidance and resources, the Social Innovations Lab model shows that the possibilities for social change are only as limited as our own imaginations.

References:

1 GreenLight Fund. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2015, from http://www.greenlightfund.org/html/home.html.

2 The Bridgespan Group. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2015, from http://www.bridgespan.org/about/Our-Mission-Statement.aspx.

3 Community Wealth Partners. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2015, from http://communitywealth.com/about-us/.

4 Centre for Social Innovation New York City. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2015, from http://nyc.socialinnovation.org.

5 Nilsson, W. and Paddock, T. (Winter, 2014). Social Innovation From the Inside Out. Stanford SOCIAL INNOVATION Review. Retrieved from http://ssir.org/articles/entry/social_innovation_from_the_inside_out.

6 Ibid.

7 Martin, Roger. (2014). The Big Lie of Strategic Planning. Harvard Business Review.

8 Bandura, A. (1991). Social Cognitive Theory of Self-Regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248-287.

9 Bandura, A. (1991). Social Cognitive Theory of Self-Regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,50(2), 251.

10 Nambisan, S. (2009). Platforms for Collaboration. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 7(3), 48.

11 Christensen, C. M.(1997). The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Create Great Firms to Fail. Harvard Business Review Press.

12 Christensen, C. M., Baumann, H., Ruggles, R., & Sadtler, T. M. (2006). Disruptive Innovation for Social Change. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 94-101; Lettice, F., & Parekh, M. (2010). The Social Innovation Process: Themes, Challenges and Implications for Practice. International Journal of Technology Management, 51(1), 139-158.

13 Bandura, A. (1991). Social Cognitive Theory of Self-Regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 269.

14 Mulgan, G. (2006). The Process of Social Innovation. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 1(2), 151.

15 This article provides seven examples of well-intentioned ideas that generate negative outcomes http://matadornetwork.com/change/7-worst-international-aid-ideas/.

16 Bandura, A. (1991). Social Cognitive Theory of Self-Regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 254.

17 Mulgan, G. (2006). The Process of Social Innovation. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 1(2), 153.

18 Ibid.

19 Shanmugalingam, C.J. Graham, S. Tucker and G. Mulgan. (2010). Growing Social Ventures: The Role of Intermediaries and Investors. The Young Foundation and NESTA, 23. Retrieved from http://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Growing-Social-Ventures-2011.pdf.

20 De Miranda, P. C., Aranha, J. A. S., & Zardo, J. (2009). Creativity: People, Environment and Culture, the Key Elements in its Understanding and Interpretation. Science and Public Policy, 36(7), 529.

21 Fabricant, Robert. (2013, March 8). Meet Your New R&D Team: Social Entrepreneurs. Harvard Business Review Blog Network. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2013/03/meet-your-new-rd-team-social-e.

22 Nambisan, S. (2009). Platforms for Collaboration. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 7(3), 46.