Summary

An estimated 1 in every 2 children in the City of Philadelphia will lose a close loved one by the time they reach the age of 18, many of whom under traumatic circumstances, exacerbating the risk of emotional and developmental problems already presented by the experience of grief at a young age. Research, however, shows that healthy grieving can help children transform their devastation into an opportunity for growth, creating a new narrative for their lives and helping foster resiliency as they move forward. Recognized as a best practices model, trauma-informed peer support groups like those offered at The Center for Grieving Children have been shown to help children process their grief, decrease the likelihood of long-term psychological issues, reduce social isolation, and reduce trauma symptoms associated with violent death.

The Need

An estimated 1 in every 2 children in the City of Philadelphia will lose a close loved one by the time they reach the age of 18. And while grief is a normal response to death, children who do not grieve in healthy ways frequently develop emotional problems, like depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem, which can inhibit academic achievement and lead to disengagement from school, family, and community.1 These negative outcomes are further exacerbated by endemic community violence and poverty issues affecting youth throughout Philadelphia. In fact, among the nation’s 10 largest cities, Philadelphia has the ignominious distinction of having the highest homicide rate for years.2 Furthermore, Philadelphia is the poorest large city in the United States and has the highest rate of deep poverty, defined as the number of people with incomes below half of the poverty line.3 These realities have a negative effect on the grief process and outcomes for youth. Traumatic circumstances surrounding the death of a loved one complicates grief further for many children, which pose further risks for these children.4 These risks include depression, anxiety, and other mental health problems. A 2014 study published in Pediatrics found that childhood bereavement leads to an academic decline, which is even more drastic when the child is underserved and/or the death occurred as a result of homicide, suicide, or overdose.5

There is hope, however. Research shows that healthy grieving can help children transform their devastation into an opportunity for growth, creating a new narrative for their lives and helping foster resiliency as they move forward. Recognized as a best practices model, trauma-informed peer support groups like those offered at The Center for Grieving Children have been shown to help children process their grief, decrease the likelihood of long-term psychological issues, reduce social isolation, and reduce trauma symptoms associated with violent death.6

The Problem

Founded in 1995 as part of St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children’s bereavement program, The Center had operated as a nonprofit since 2000 with the goal of providing free grief groups to youth ages 5-18 who had experienced the death of a close loved one and by training front-line professionals to better support grieving youth. Over this time, though, The Center had struggled to serve more youth, despite the overwhelming number of youth suffering in the city. By 2012, The Center’s numbers had dropped to an all-time low; only 25 youth served. In a city where an estimated 15,000 to 17,000 will lose a close loved one each year, The Center knew it needed to evolve.

Under new leadership and as part of a strategic planning process, The Center realized that it needed to examine publicly available data and literature to determine what the needs were within the City of Philadelphia for grieving youth and how it needed to shift its model and services to meet this need.

The Data and Literature

The data painted a stark picture:

- 35% of Philadelphia residents had no access to a vehicle, making service access more difficult;

- 65% of women who gave birth in the prior 12 months were single-parent households, raising the number of children who would lose their only caregiver;

- Nearly 20% of residents did not graduate high school, limiting knowledge of resources; and

- 28% of households were living below the poverty line, complicating access and raising risk factors for grieving youth.7

The data also demonstrated the greatest needs in specific neighborhoods that could not easily access The Center’s free grief groups at the time: Lower Northeast Philadelphia, West Philadelphia, and Southwest Philadelphia. Examining the publicly available data, all three of these neighborhoods had crime rates anywhere between 115-200% higher than Pennsylvania’s, and 39-67% higher than the Philadelphia average. These neighborhoods ranged from median salaries below the poverty line to less than 133% above the poverty line, meaning less resources available for support. (City-Data.com 2013).7

A literature review revealed additional obstacles. A review of literature about historically underserved, grieving, urban youth demonstrated the need to make services highly accessible to youth dealing with community-level trauma8 and to expand the definition of close loved one, allowing the clients to decide.9

The Innovation

Around the country, there are more than 250 children’s bereavement organizations. These models are all based on a suburban-style model where there is a central location and all grieving families drive to the location. The data demonstrated that this model was not going to work for The Center for Grieving Children. Philadelphia is a city of neighborhoods where many people who need services lack the resources or transportation to access them. Further, with so many youth and families dealing with violence and poverty in their communities and lives, access is even further reduced, and therapeutic interventions must recognize these realities.

As a result of its data collection and literature analysis, The Center turned the national model on its head. Beginning in the Fall of 2013, The Center began running satellite locations in addition to its East Falls headquarters. Partnering with respected and trusted institutions like the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Calvary Christian Church, The Center has four locations where youth and their caregivers can access free grief support: East Falls, West Philadelphia, Lower Northeast Philadelphia, and South Philadelphia. While some of these locations are only a few miles from one another, for clients with limited resources, this mileage and the public transportation to a closer location makes all the difference. This expansion of locations has allowed The Center to increase the youth served from 25 to 174 in the last program year.

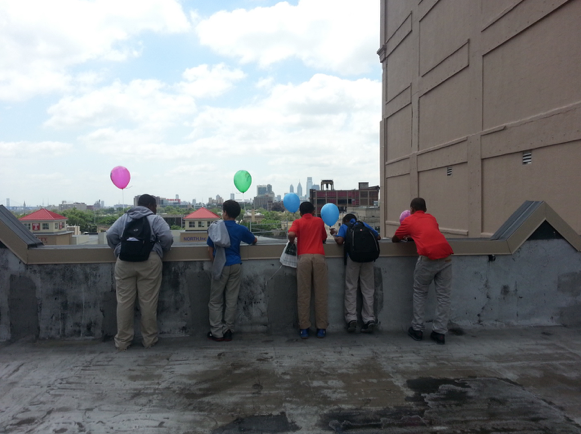

At the same time, The Center launched Community-Based Programming, shorter term grief groups (8 weeks) offered at community locations like schools and community centers. Working with the school counselor and providing grief groups during the day to the students where they are removed an additional barrier to attending. In the three short years that The Center has provided these groups, they’ve grown from 25 students in 3 schools to a staggering 411 youth in 50 schools served this last year. Further responding to additional data demonstrating high levels of grief among adjudicated youth, The Center expanded this Community-Based program for adjudicated youth at evening reporting rooms and detention centers.

Both the site-based locations and Community-Based Programming use an evidence-based curriculum that draws upon Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, among other theories. These curricula ground The Center’s work, create consistency of delivery, and make the model expandable and easily replicable.

No other children’s bereavement organization in the country has developed such a robust, community-based model for an urban city like Philadelphia. In fact, on a national level among its peers, The Center is recognized as a leader in providing grief support and resources to underserved, urban youth and their families. Because of this expertise, The Center is looking for ways to expand its model to under-resourced communities in and around the City of Philadelphia.

The Limits

Due to the high need in Philadelphia, the greatest limit to The Center’s grief services is capacity. The Center for Grieving Children is completely privately funded through the generosity of donors and foundations. While The Center is actively working to expand its work, it needs the financing to do this.

Another limitation of The Center’s model is community buy-in. With so many neighborhoods in the city, there are a variety of stakeholders with whom relationships must be forged and trust built. As the Center tries to expand, this only expands the list of stakeholders. Further, it is important to allow communities to have self-efficacy, so it is also important that the community has a voice and a role in this service delivery.

Like the role it has played in shaping The Center for Grieving Children’s delivery of services, data can also play a role in reducing limitations, including assisting in the identification of communities and stakeholders. Data is critical to the success of community organizations in assisting the most vulnerable individuals. The Center for Grieving Children has learned this lesson firsthand and is committed to continued data analysis as it carves out its future.

Author bio

Darcy Walker Krause, J.D., LSW, C.T., is the Executive Director at The Center for Grieving Children in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The Center provides free grief programming to youth age 5-25 and their caregivers as well as trainings and post-crisis intervention for professionals and schools throughout the City of Philadelphia. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Policy & Practice and Duke University School of Law, Ms. Krause practiced Labor & Employment law in private practice for five years before moving into the non-profit sector. Ms. Krause has been a guest lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania and Temple University, published by the Philadelphia Daily News, and presented at many professional conferences, including the Association for Death Education & Counseling and the National Alliance for Grieving Children.

References:

1. Irene Searles McClatchy, Melizabeth Vonk, and Gregory Palardy, “The prevalence of childhood traumatic grief: A comparison of violent/sudden and expected loss,” Omega 59, no. 4 (2009): 305-23, doi: 10.2190/OM.59.4.b.

2. “Philadelphia 2015: The State of the City,” The Pew Charitable Trusts (March 28, 2015), accessed November 8, 2016, http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2015/03/philadelphia-2015-the-state-of-the-city.

3. Alfred Lubrano, “Among the 10 largest cities, Philly has highest deep-poverty rate,” Philadelphia Inquirer (September 30, 2015), accessed November 8, 2016, http://www.philly.com/philly/news/local/20150930_Among_the_10_largest_cities__Phila__has_highest_deep-poverty_rate.html.

4. Judith A. Cohen, Anthony P. Mannarino, and Kraig Knudsen, “Treating childhood traumatic grief: A pilot study,” Journal of Am. Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 43, no. 10 (October 2004): 1225-1233, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000135620.15522.38.

5. Lisa Berg, Mikael Rostila, Jan Saarela, and Anders Hjern, “Parental death during childhood and subsequent school performance,” Pediatrics 133, no. 4 (April 2014): 682-689.

6. Monika Metel and Jacqueline Barnes, “Peer-group support for bereaved children: a qualitative interview study,” Child and Adolescent Mental Health 16, no. 4 (2011): 201-07, doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00601.x.

7. “Philadelphia 2013: The State of the City,” The Pew Charitable Trusts (March 24, 2011), accessed November 8, 2016, http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2013/03/23/philadelphia-2013-the-state-of-the-city.

8. William R. Saltzman, Robert S. Pynoos, Christopher M. Layne, Alan M. Steinberg, and Eugene Aisenberg, “Trauma/grief-focused intervention for adolescents exposed to community violence: Results of a school-based screening and group treatment protocol,” Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice 5, no. 4 (2001), 291-303, doi: 10.1037//1089-2699.5.4.291.

9. Carole A. Winston, “African American grandmothers parenting AIDS orphans,” Qualitative Social Work 5, no. 1 (2006): 33-43, doi: 10.1177/1473325006061537.