Currently, most voters enter the voting booth confident in their choices for president or senator and unprepared for the rest of their ballot. As a result, voters guess, leave blanks, or stay home from elections altogether.

Real democracy requires informed votes. That’s why we founded BallotReady, an online nonpartisan voter guide to every race and referendum on the ballot. By providing accessible information on candidates, ballot measures, and how to vote all in one place, our aim is to radically boost vote quality and voter turnout at all levels.

Last fall, we were live in 12 states, with information on 15,000 candidates and over one million visits to our website. Now we’re preparing to scale nationwide by November 2018, all the way down the ballot.

There are half a million elected officials and they matter - a lot

There are approximately 525,000 elected officials in the United States (Lawless 2011), and the vast majority - 96 percent - are elected locally. These officials serve in municipal and county governments, on school boards and in special districts, and compared to federal politicians, they are relatively unknown and rarely covered by the media. But they also make decisions that affect our lives every day: levying property taxes, monitoring water quality, and choosing the leadership for our schools.

Considering their significance, it’s staggering how many local officials are elected based on guesswork. Voters in local elections often rely on incumbency, ethnicity, or even ballot position when deciding who to vote for. According to the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics, candidates listed first on the ballot receive up to five percent more votes. Not all voters guess - some simply leave parts of their ballot blank. Wattenberg, et al. (2000) compare voting to taking the SAT - voters, like students, skip questions when they feel uninformed. Finally, as has been well-documented, many voters stay home. Portland State University found that local election turnout in 10 of America’s largest cities was less than 15 percent, while he median age of voters was 57.

The implications are significant. Hajnal (2010) finds that low turnout leads to less equitable racial and ethnic representation on city councils. Berry and Gersen (2010) report that policy outcomes tend to favor special interests. More broadly, as Harvard professor Rohini Pande argues, “a well-functioning democracy requires voters to be informed.”

BallotReady: Vote informed, every race, every election

BallotReady is a nonpartisan online voter guide to every race and referendum - our mission is to make it easy to vote informed on the entire ballot. BallotReady provides nonpartisan, comprehensive information on every candidate and measure by aggregating content from candidate websites, endorsing organizations, newspapers, and boards of election. We do this in two ways: first, we use structured crowdsourcing to pull in all online information about a given candidate. Second, we are developing automated collection processes through a partnership with IBM Watson. IBM Watson is learning how to tag issue stances and pull endorsements from a candidate’s website.

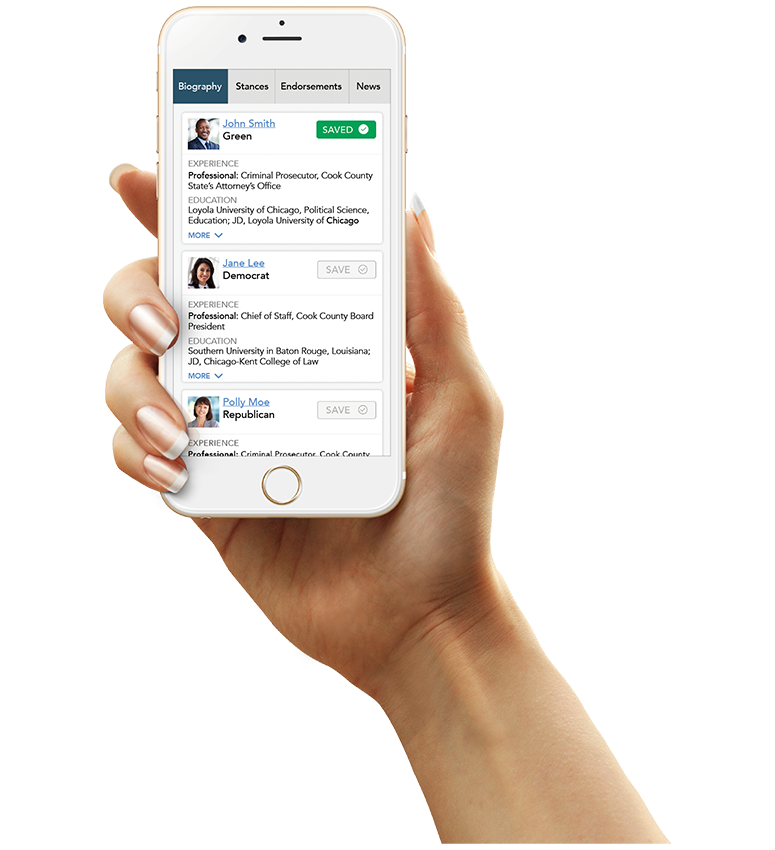

Voters who come to our site enter their address to view their entire personal ballot. From there, voters can compare candidates based on their respective biography, endorsements, issue stances, and news articles. Once they’ve decided, voters can save their choices to print at home or pull up on their phone, in the voting booth.

We are cognizant of the importance of limiting any bias. Every piece of information on BallotReady’s website is linked back to its original source and we make a dedicated effort to reach out to all candidates. We also show candidates in random order to minimize the effect of being listed first on the ballot.

We built BallotReady through continuous iteration. In January 2015, our team conducted interviews with 150 voters to validate this problem and our solution. Our very first voter guides were made of paper; we asked Chicago voters to highlight what information they found useful in making a voting decision. Using their feedback, we piloted a very simple voter guide for the April 2015 Chicago mayoral runoff. Though lacking key features, we were able to prove our first basic assumption: voters were willing to research their entire ballot.

From there, we built a fully functional website that we continue to test and improve. We were live for Kentucky’s November 2015 election and throughout the 2016 spring primaries, before launching in 12 states for the fall 2016 general election. In 2016, we compiled information on 15,000 candidates and saw over one million visits to our site.

Measuring impact and creating a more informed democracy

In the long term, we believe accessible information creates more informed voters, who in turn elect better officials and strengthen their communities. In the short-term, we are focused on measuring two substantial outcomes.

First, BallotReady aims to increase the number of informed votes. Specifically, we aim to reduce the number of voters who do not complete their ballot and the election of candidates of poor quality, such as those under criminal investigation. We have already seeing evidence of this effect. Voters who used our site in 2016 viewed an average of seven races and were less likely to save judicial candidates who received a “Not Qualified” bar association rating.

Second, BallotReady aims to increase voter turnout. Last year, a team at MIT found that BallotReady users were 20 percent more likely to vote, even after controlling for demographics and past voting behavior. We’re now designing a more rigorous randomized controlled trial for 2017.

Differentiation: Making paper guides digital

Voter guides are an established part of our democracy. The most well-known are published by newspapers, political parties, and governments themselves. Many voters have become accustomed to tearing out their local newspaper’s endorsements and bringing them into the voting booth.

Paper voter guides, however, have several shortcomings: they can’t be customized to show an individual’s personal ballot, they can’t filter based on a voter’s preferences, and they cater to an older audience; millennial voters are unlikely to subscribe to print newspapers.

In the past decade, several nonprofits have worked to bridge this digital gap. However, no existing voter guide has been able to aggregate the same breadth and depth of information as BallotReady. Most voter guides rely on candidate questionnaires with response rates of 50 to 80 percent. As a result, they provide high-level information on presidents and senators but lack robust content on the candidates whom voters know the least about. Additionally, no current voter guide has been designed specifically to be used on smartphones in a voting booth, an innovation targeted at millennial voters.

A sustainable, for-profit model

BallotReady incorporated as a for-profit in 2015. We believe this structure grants us the greatest leverage to scale quickly and be sustainable long-term. To date, we have been funded by grants and a round of investment from organizations like the National Science Foundation, the Knight Foundation, and the University of Chicago. We are building a sustainable business model around creating custom voter guides for nonprofits, advocacy groups, and civically-engaged companies designed to inform and get out the vote. Under this model, 501(c)3s can help members find candidates that share their values and 501(c)4s can send out their endorsements, personalized by address. Our embedded research-based turnout tools prompt voters to create a plan to vote, with polling place matching, text message reminders, and instructions for voting by mail. Our goal is to reduce all friction in voting, especially in local and midterm elections.

Roadblocks and the future of voting

BallotReady’s most significant challenge remains the lack of information at the local level around political boundaries and sample ballots. District boundaries can live in anything from GIS shapefiles, online PDF maps, or on paper in district filing cabinets. BallotReady makes hundreds of calls to boards of election to collect boundaries for municipal or special districts.

BallotReady also requires accurate candidate lists. While it may sound surprising that candidate lists are not readily available, research by the Center for Tech and Civic Life has found that 30 boards of election lack any website that provides election information. Across the country, civic coalitions of foundations, nonprofits, and companies like Google and Microsoft, are working to modernize the existing election infrastructure. Nevertheless, there continues to be large holes, particularly for local districts, primaries, and off-year elections.

These challenges are worth solving, because we believe that the policy implications of accessible information on voting are enormously worthwhile. We hope BallotReady becomes ubiquitous - the go-to step before voting. With a more informed electorate, candidates at all levels will know that they will be held accountable for their record. With increased voter turnout, our democracy will become more representative and we can better ensure we elect the best half million for the job.

Conclusion

Voters across the country have demonstrated that they are willing to spend additional time preparing to vote if the barriers to researching candidates are removed. We are motivated to continue to test, improve, and grow to create a country where everyone can enter the voting booth BallotReady.

Aviva Rosman Bio

Aviva Rosman is the COO and co-founder of BallotReady, an award-winning voter guide to every race and referendum on the ballot. Beginning in middle school, Aviva has worked on campaigns at all levels, including her own successful run for local office. She began her career teaching high school math and leading the special education department in Chicago as a corps member with Teach for America. Aviva has a BA and masters’ degree from the University of Chicago, both in public policy.