SUMMARY

Philadelphia’s Community Behavioral Health (CBH) is one of the nation’s leaders in adapting a pay-for-performance system to the world of behavioral health care. Five years ago, CBH adopted pay-for-performance incentives more typically seen at medical facilities providing care for physical ailments and applied them to behavioral health care providers. This approach has now expanded to more than 90 percent of the behavioral health care providers in CBH’s network.

Pay-for-performance offers financial incentives to providers based on a patient’s outcomes rather than on each individual step in the process of treatment. Community Behavioral Health uses a series of metrics to evaluate behavioral health care providers. Providers who achieve these benchmarks receive payments at the end of the calendar year proportional to their revenue and scaled to their scores on the metrics. What’s unusual about CBH’s approach is the latitude it offers to providers as to how they can go about meeting the metrics. It’s a system that encourages competition and focuses on outcomes, not the steps taken to get there.

Pay-for-performance proponents decry the more traditional fee-for-service model as outmoded and perverse. Health care providers are generally for-profit entities, they say, and under a more traditional system, the profit incentives are greatest when a patient is in more critical condition. To use an example, a hospital makes more money when a patient with high cholesterol gets a stent implanted than if that patient is able to avoid a blot clot entirely through responsible medicating and healthy eating.

CBH’s chief medical officer (CMO), Dr. Matthew Hurford, described how the traditional financial model for health care rewards all of the wrong behaviors.

“The sicker you are, the more hospital services you use, the more money the provider makes,” Hurford said.

The pay-for-performance approach is getting results. Statistics show that more people are getting more and faster outpatient treatments and are avoiding unnecessary admissions to inpatient treatment facilities.

Introduction

When it comes to behavioral health, a patient’s success is rarely the result of the work done by one doctor or the effectiveness of one procedure. It’s a spectrum of care that offers the best chance of health and full participation in society for people suffering from behavioral issues ranging from alcoholism to depression to schizophrenia. Patients have the best outcomes when there is a seamless interaction between emergency care, inpatient treatment, outpatient facilities and social support networks. Unfortunately, the typical payment structure for behavioral health providers is based on services provided, so payment comes per individual treatment session or doctor’s appointment. This is a structure that doesn’t encourage the continuum of care that may best suit these patients.

In addition, pay-for-service models can be expensive. Providers can rack up big bills on therapy, treatments, medications and tests without any regard to the long-term impact on the patient. In Philadelphia, approximately 460,000 people are eligible for behavioral health care coverage through Medicaid. According to a 2012 study in Psychiatric Services, schizophrenia inpatient treatment over 11 days costs about $8,500. About nine and a half days of inpatient treatment for bipolar disorder costs approximately $7,600, and six days in alcoholism treatment costs an estimated $5,900. If just a percentage of the 420,000 people eligible for Medicaid coverage require inpatient services, the cost can quickly become oppressive.

A 2012 overview of pay-for-performance in Health Affairs noted that the current payment structure for health care can actually be detrimental for patients in that it creates incentives for providers to increase a patient’s volume of care rather than focusing on the effectiveness of that care.

“Higher intensity of care does not necessarily result in higher-quality care, and can even be harmful,” that article stated.

A New Model

Community Behavioral Health, a not-for-profit managed care organization founded in Philadelphia to manage the behavioral health benefits for Medicaid enrollees, is among the first behavioral health organizations in the country to eschew the pay-for-service model in favor of a pay-for-performance approach. They are changing the culture of how mental and behavioral health issues are addressed for the 460,000 Philadelphians eligible for Medicaid. The fundamental shift toward pay-for-performance from a more traditional pay-for-service model comes from creating an environment in which providers are rewarded for a patient’s overall health and productivity, not for the individual tests and treatments a patient receives.

“The goal is not to say ‘these (services) are billable,’” CMO Hurford said in an interview this August. “Here are the outcomes we want. Here’s the money. Do it well and you’ll be profitable. If you don’t do it well you won’t be.”

In the past five years, Community Behavioral Health has incrementally rolled out pay-for-performance systems for 90 to 95 percent of the providers who service Philadelphia’s Medicaid population. That means that inpatient hospital providers, for example, receive a fixed per diem and are subject to evaluations based on a series of indicators using information available through Medicaid claims forms. At the end of the calendar year, the hospitals are eligible for incentives the size of which is determined by their evaluation scores and their annual revenue.

Pay-for-performance began in Philadelphia in 2007 after the state’s Medicaid program, HealthChoices, made $9 million available statewide for Medicaid managed care organizations like CBH to begin pay-for-performance programs. Community Behavioral Health took the initiative to come up with a homegrown model of pay-for-performance to ensure a good fit for Philadelphia. The influx of state money supporting pay-for-performance was an indicator for providers that this new method was a serious change for Medicaid payments in Pennsylvania and that they stood to profit if they got on board.

Once the state approved Medicaid payments based on pay for performance, CBH held a series of collaborative meetings with providers to develop and refine performance metrics. Implementing pay for performance represented a culture shift for providers in Philadelphia. Providers accustomed to cost-of-living increases in their rates have seen that disappear, replaced with the end-of-year bonuses that come with positive performance.

Measures of Effectiveness

The umbrella of behavioral health is wide. CBH oversees services ranging from adult mental health inpatient providers to childhood trauma therapists, from drug addiction rehabilitation centers to homelessness services. There are 60 different evaluation metrics used over 11 or 12 levels of care, but every metric isn’t used for every provider. Instead, CBH determines a few of the 60 metrics that are most applicable to a specific provider. In general, evaluation metrics focus on performance in areas such as speed of access to care, follow-up after a patient is treated and patients’ recidivism rates after treatment. These are pieces of information that providers are required to report through Medicaid claims forms, and they allow CBH to look at results more than processes.

Pay-for-performance in Philadelphia is focused on outcomes, so providers have a great deal of flexibility in how they go about reaching those benchmarks. These metrics are used not just to evaluate providers’ effectiveness but to determine the effectiveness of pay-for-performance itself. By reviewing data that quantify speed of care or recidivism, for example, CBH can determine whether pay-for-performance is having an effect on patients’ outcomes.

The key metrics for Philadelphia are measures of follow-up, case management and recidivism. When deciding on the metrics to use, CBH staff felt it was important to keep it simple. Experience has shown that benchmarks must be carefully considered and few in number. Too many and providers become overwhelmed and end up failing to meet standards.

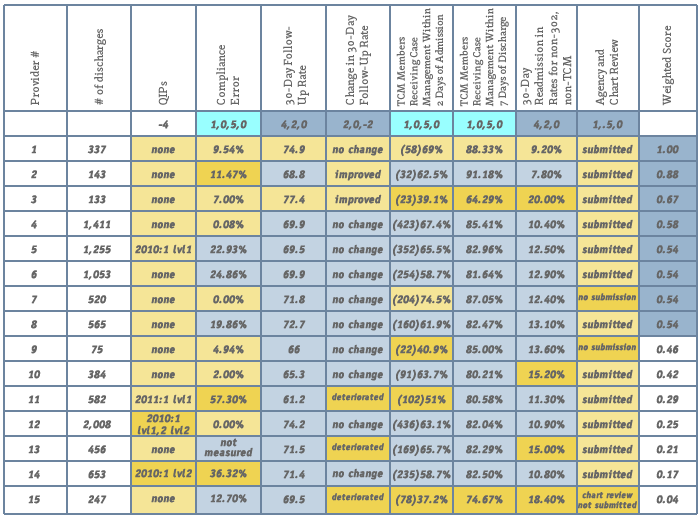

A sample of a 2011 evaluation matrix for adult inpatient providers shows that providers are evaluated by time frames. Did the patient receive a follow-up within 30 days? How quickly did the patient receive case management? Perhaps most importantly, was the patient readmitted to inpatient care within 30 days of being discharged? Evaluation forms are color-coded. Green is good. Red is poor. Yellow indicates performance somewhere in the middle.

SAMPLE COMPARATIVE EVALUATION SHEET

As an example of pay-for-performance’s success, and the different ways providers can achieve success, Dr. Rebecca Robare, research analyst coordinator for CBH, used improvement in the rate of long-term inpatient drug rehabilitation clients who received post-discharge treatment. Robare reported in an August interview that from 2010 to 2011, there was a 16 percent increase in the number of Medicaid clients in rehab who received follow-up care after discharge. Across the board, providers were doing better, but their techniques varied. One provided shuttle vans to transport clients to outpatient centers. Others developed close relationships with outpatient providers and others opened their own outpatient services to complement their inpatient facilities.

“I think it’s very flexible,” Robare said. “We want providers to engage in certain behaviors that make certain outcomes more likely, but what we’re really incentivizing are the outcomes, not the behaviors themselves.”

Of course, another possible determiner of pay-for-performance’s effectiveness is the money saved through this approach. For the time being, CBH officials say it’s too soon to be able to determine whether this approach is resulting in savings. They say the numbers just aren’t there yet.

Philadelphia Flavor

In the search for an alternative to the pay-for-service model to behavioral health care, options other than CBH’s pay-for-performance approach are being tested. One, for example, puts more of an emphasis on the potential financial benefits of pay-for-performance. The end-of-year payment for providers in this model is a percentage of the savings that a provider reported compared with previous financial reports. Another model offers the patients, not the providers, money for behaviors likely to lead to improved overall mental health. What drives CBH’s pay-for-performance model, though, is the cooperation and contributions of the providers themselves. Collaboration is key to CBH’s efforts to make pay-for-performance a standard payment approach to Medicaid in the city. The metrics CBH uses compare Philadelphia providers with comparable businesses both within the region and nationally in order to establish appropriate local provider benchmarks. Though the providers are compared with each other for the purposes of evaluation, they are not in competition for the financial rewards that come with meeting the CBH benchmarks. The pay-for-performance system is designed to raise all boats rather than rewarding only the most effective providers in the city. Instead of offering financial incentives to the providers with the highest scores, CBH has established a system within which every provider could receive end-of-the-year financial incentives by meeting the benchmarks.

“Our goal here is not to make this a competitive process,” Hurford said. “We want this system to reach a benchmark of less than 10 percent. If every one of you gets your recidivism rate that low, everyone gets paid.”

Because the providers aren’t in competition with each other for incentive money, there is a culture of cooperation within Philadelphia’s provider community. CBH highlights innovative providers in the city and arranges coordination with like providers. And providers are receptive. Providers are invited to more than ten meetings annually to discuss levels of care, and CBH is working to increase its use of electronic communications with providers. Transparency is maintained throughout, with providers being made aware of the measures they’ll be evaluated on and having the chance to discuss evaluation with CBH. Hurford noted that CBH has never had a provider unwilling to offer suggestions on techniques that have been shown to work, or one who was uninterested in hearing what worked and how it could be adapted.

Providers agree that sharing the pay-for-performance system encourages improved service and builds on existing relationships among the city’s health care providers. Antonio Valdés, CEO of Children’s Crisis Treatment Center, a Philadelphia organization devoted to assisting children with behavioral health issues, said he sees a powerful motivation to cooperate among his peers.

“There’s a lot of helping each other out,” he said in an interview this summer. “People do visits to each other’s sites. It’s not terribly competitive.”

This collaborative system allows for a significant amount of innovation to bubble up from providers themselves rather than being mandated by CBH. The Medicaid provider is evaluated based on metrics that focus on results, not process. Rather than trying to meet a set of metrics that evaluate a prescribed number of therapy sessions per patient, or the number of Alcoholics Anonymous meetings a patient attends, providers are encouraged to use their experience and insight into the people who need behavioral health to offer ideas on how to serve them best. Making available a continuum of care is the one of the most encouraged ways to achieve high marks on evaluations. To do this effectively, providers are encouraged to be aware of the people who are receiving treatment and what their needs are. Serious mental illness is disproportionately represented in the lower socioeconomic strata, said Dr. Hurford, CMO for the city’s Department of Behavioral Health as well as for CBH. Mental illness is associated not just with poverty but with unstable housing and limited social supports.

“These present real barriers to being able to access care,” Hurford said.

Mental illness brings with it other challenges that providers should be prepared to address and mitigate. People with schizophrenia are more likely to have issues with paranoia, for example, while people with anxiety are more prone to have trouble using public transportation.

Providers are incentivized to emphasize linking patients with outpatient facilities in the patients’ communities, to provide what Hurford describes as a “warm handoff” between inpatient and outpatient treatment facilities. Community Behavioral Health has incentivized providers to spend time introducing a patient to a local outpatient clinic, for example, to ensure that the person isn’t relying on emergency or crisis care for treatment. Discharge plans need to be more thorough, so providers are rewarded for ensuring that patients are sticking to their recovery plans through follow-up phone calls.

“The providers need to make a commitment to invest in interventions and practices that are likely to increase the outcomes,” Hurford said.

The better a provider is at managing a continuum of care, the greater the likelihood of positive patient outcomes and, consequently, the larger the incentive payment the provider is likely to receive at the end of the year.

Pay-for-performance is nothing new. It’s been implemented widely across many disciplines, like education and health care, though it has less frequently been applied to behavioral health. When it comes to physical health conditions like heart disease, broken bones and diabetes, insurance companies have created carrot-and-stick incentives that induce hospitals to find ways to prevent injury, infection or poor treatment that could extend a patient’s hospital stay. The idea has caught on. According to a May 20, 2011, New Republic article on pay-for-performance, only 52 such programs existed in the United States in 2003. By 2007, that number was up to 256. The Affordable Care Act mandated that Medicare find ways to pay hospitals based on outcomes rather than on the treatments being provided.

Though there are challenges and issues unique to people with mental and behavioral disabilities, the differences between medical health and behavioral health are less significant than they might appear, Hurford said.

“I think the challenges are unique with any population but it depends on what altitude you take a look from. On a very high level, the outcomes are universal. You want people to recover and have a full and productive life.”

He noted that whether someone suffers from diabetes or depression, providers have to account for human behavior. People don’t take their medicine. They don’t show up for appointments. These and similar factors impact how effectively people manage and recover from their conditions, and they’re things that providers can influence to tilt the odds in the favor of patients’ developing functioning, healthy lives.

Much of CBH’s success in implementing a pay-for-performance system stems from the fact that Philadelphia’s behavioral health community was already experimenting with holistic approaches that didn’t treat patients as the subjects of an assortment of procedures and treatments but as people who could be assisted in building full, productive lives through myriad services both within traditional health care and complementary to it. The pay-for-performance model in Philadelphia encourages peer review and sharing ideas among providers. Financial incentives are designed to reward not just the best providers but all of the city’s behavioral health care providers for meeting certain standards.

Philadelphia had some built-in strengths that made it an ideal seedbed for an innovative application of pay-for-performance to behavioral health. Many give credit to Dr. Arthur Evans, commissioner of the city’s Department of Behavioral Health, for having the vision to push for an outcome-oriented approach to pay for performance in the city.

Community Behavioral Health’s structure itself contributed to making the environment friendly to pay for performance. While it is an independent not-for-profit, CBH has close links with the city’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services (DBHIDS) which oversees all of the public sector behavioral health, making it easier to mandate provider policies. In addition, CBH has easy access to other city departments such as Housing and Health and Opportunity, something a private MCO can’t offer. With CBH’s emphasis on making connections to provide a full continuum of care for patients that goes beyond traditional health care, those relationships are vital. Because of its unique status as both a not-for-profit and an extension of city government, CBH was in a position to be an effective arm of Evans’s vision for health care in the city.

Another contributing factor was Philadelphia’s record of being progressive on mental health issues. Some behavioral health care providers were moving toward a more holistic approach to treatment even before pay for performance began incentivizing such methods.

In implementing pay for performance, Community Behavioral Health also appealed to providers’ sense of responsibility. Too often, behavioral health care—and actually all kinds of health care—creates facilities with a revolving-door philosophy: patients rotate in and out for procedure after procedure without anyone’s looking at the whole picture of the patient’s quality of life. Pay for performance offered a broader vision that could improve the lives of real people by offering them more stability and a continuum of care.

Experts and providers in behavioral health care noted that the challenge of pay for performance is ensuring that the indicators being evaluated are properly tailored for the services the provider offers, noting that results can provide an inaccurate picture of a provider’s effectiveness without quality metrics. Philadelphia has built into its pay-for-performance model continuous communications with providers to judge the fairness of metrics used for evaluation and tweak them as needed. The metrics used for evaluation are continuously updated to keep up with the realities on the ground among clients and new information on best practices in assisting people with behavioral health issues.

“We’re very fortunate in Philadelphia in the DBH and CBH that the leadership we have now are interested to hear feedback,” said Valdés.

Early Results

A few examples of Philadelphia success stories illustrate the impact pay for performance can have on real people in the behavioral health system. The innovation encouraged by pay for performance has developed some great ideas. Jeff Wilush, CEO and president of Horizon House, Inc., runs an organization that has been a leader in promoting a peer culture among fellow providers. That organization has woven

the pay-for-performance ideal into its very culture, touting on its website that it approaches mental health care with a holistic model designed to address psychiatric, medical and behavioral issues as one.

“You have to be able to talk to the people you serve,” he said in August. “Our system is about serving people. You need to find out what works for them.”

Horizon House also makes a policy of communicating with partners and funders to learn what’s working for them. The organization looks at the latest literature in their field to identify trends and new research to anticipate what new and effective treatments are gaining currency, he said.

CBH’s Dr. Hurford cited Northeast Treatment, or NET, which recognized that one of the greatest impediments for women who were seeking addiction treatment and rehabilitation was a lack of child care. The substance abuse treatment center opened a learning center to provide the children of women seeking treatment with a safe and educational environment. There is no additional charge to the patients or to Medicaid for this service. NET offers it as an investment designed to create better outcomes for women. And it worked. The women who brought their children to the learning center showed a reduced relapse rate.

Valdés’ Children’s Crisis Treatment Center, or CCTC, adopted a Sanctuary model, a philosophy of communication, nonviolence and teaching responsibility designed to help children recover a sense of worth and agency after witnessing events that might have left them feeling helpless and distraught. Trauma causes its victims to stop looking forward to the future, Valdés said. The Sanctuary approach focuses treatment on helping patients recover a sense of safety, not simply physical safety but also emotional security. This philosophy has been instilled in staff throughout CCTC, regardless of the client populations they work with, and because of pay for performance it has been shared with providers for children throughout the city.

The numbers show improvement in a number of areas as well. Hurford cited recidivism rates for adult inpatient clients. Before pay for performance, 15 to 16 percent of adult patients would return to an inpatient facility within 30 days. More recently, that number is down to 11 percent. Hurford would like to see it reduced to less than 10 percent.

Along with the improvement in inpatient drug rehab clients who received timely follow-up care, CBH’s Rebecca Robare pointed to visible improvement in the overall rate of inpatients who are contacted by a case manager within two days of admission. This number improved 10 percent from 2010 to 2011.

Will It Work Elsewhere?

When implementing pay for performance, CBH staff didn’t try to reinvent the wheel. They saw the existing strengths in the behavioral health care community and worked to capitalize on those by taking the best of what was already being done and making it systemic. They also ensured that there was communication and engagement with stakeholders in the city. The message was not that they were going to turn providers’ operations upside down but instead that they were going to create standards that would make providers better and more effective at what they were already doing.

Providers who have done well under the pay-for-performance model have emphasized the importance of anticipating new metrics before they become part of the evaluation process.

“It’s constantly changing and constantly in motion,” CEO Wilush said. “If you wait until someone tells you what your target ought to be...if you wait for the standards, it’s going to be gone.”

Horizon House offers a full range of services to individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, addiction, behavioral health disorders and homelessness. Many of the holistic care ideas encouraged by pay for performance were already part of Horizon House’s approach, he said. He sees pay for performance as a model that encourages habits that providers should be embracing anyway.

Financial Questions

An unanswered question about Philadelphia’s experiment with pay for performance is whether it actually saves money. As stated earlier, CBH staff say it’s too soon to say whether the impact of pay for performance in behavioral health includes reduced health care costs. Nationally, the picture isn’t much clearer. Most behavioral health care pay-for-performance programs haven’t been around long enough for clear patterns to have emerged—a 2008 Psychiatric Services look at how pay for performance was being applied in mental health found only 24 such models— and of those that exist, many make improved care, not savings, the priority.

“...states and managed care plans have designed P4P programs to improve access, quality of care, patient experience and to foster provider participation in the program,” says a Texas report on the impact of pay-for-performance. “Where cost-effectiveness has been a consideration, the P4P program sponsor is typically interested in the program being cost-neutral. For this reason, there is virtually no research assessing the cost-effectiveness of P4P.”

It’s also difficult to quantify the financial impact of pay–for-performance on society because of the broad range of individuals and conditions CBH’s Medicaid dispersals cover. The potential savings from reducing people’s time spent in inpatient care, for example, is difficult to specifically calculate because there are such varying lengths of stays and costs associated with different conditions. According to a study in the German Journal of Psychiatry, the average stay for patients admitted for bipolar disorder is 15 days, for depression 11 days and for schizophrenia 21 days. For Philadelphians, according to the U.S. Census, the average daily income in a 262-day work year is $80.59. If the average of those three conditions’ lengths of stay is 16 days, then avoiding a hospital stay is worth $1,249 in wages that would otherwise be lost. With the 420,000 possible consumers of Philadelphia’s Medicaid behavioral health care providers, that’s $541,564,800 in preserved wages throughout the city.

Challenges

Both CBH staff and the city’s behavioral health care providers agree that there is still work to be done to make pay for performance more effective. Community Behavioral Health uses Medicaid claims forms as the source of the metrics data to be evaluated so as to avoid creating work for providers, but that also means that there are areas of care that cannot be evaluated because there is no Medicaid reporting requirement. Long-term outcomes, providers’ ability to make proactive phone calls to clients, the number of foster children who are successfully returned to their biological parents...these are important statistics that can’t be measured under the current system.

“We would love to be able to incentivize effective behaviors directly, but right now it comes down to what we’re able to do with the current systems in place is to incentivize those outcomes,” Robare said.

Community Behavioral Health is limited in its ability to encourage a more holistic approach because of those services that Medicaid doesn’t cover. Medicaid currently doesn’t cover more proactive services like alcohol prevention programming, mental illness treatment and mental health promotion or psychoeducation for patients and families living with serious mental illness. Ideally, all of these would be part of a patient’s continuum of care, but for now they are funded by state entitlement money, and only 3 percent of Pennsylvania’s $1 billion in entitlement spending goes toward prevention services.

“We want to have the ability to be able to say to a provider that there is an amount of money for the people you are assuming responsibility,” Hurford said. “Here are the metrics we’re going to hold you responsible for. You should make the interventions that you think would be more helpful.” Providers, meanwhile, said the evaluation system is still a work in progress. There are concerns that some metrics aren’t finely tuned enough to evaluate something as complicated as behavioral health can be.

The conversations with providers as pay for performance was introduced, and in ongoing conversations during the past five years, involved making it clear there were national data to demonstrate that things like recidivism could be affected by certain measures, and that they could be measured fairly.

Providers were also concerned that they would be held to the same standards as radically different behavioral health care facilities. A nonprofit devoted to working with schizophrenia patients is going to have very different recidivism rates and outcomes from those of an organization that works with people trying to recover from alcoholism. Community Behavioral Health personnel acknowledged this as a legitimate concern, and in the comparative evaluations, they ensure that providers are compared only with other providers who serve similar populations. This allows the unique conditions of different types of treatment to be taken into account and ensures that providers working with the most sensitive and challenging populations aren’t penalized.

“We all want the same thing,” Hurford said of his conversations with providers. “We want you to deliver the best possible care.”

President Wilush noted that in some kinds of treatments, his organization (Horizon House) has done very well on the CBH evaluation forms. In other cases, they have decided to not try to chase evaluation metrics that aren’t effectively measuring their success. One example he used was a drug recovery inpatient program Horizon House operates that has clients who receive post-discharge therapy outside of the Philadelphia area. As a result, CBH will not receive the Medicaid claims from those outpatient services that were delivered outside of Philadelphia and thus they cannot confirm that these patients are receiving a continuum of care.

Also in question is the long-term effectiveness of pay for performance as a means to streamline and improve behavioral health care. Because it is a relatively new approach, not many conclusive studies are available on its value, but some looks into pay for performance in the medical field have led to ambiguous conclusions.

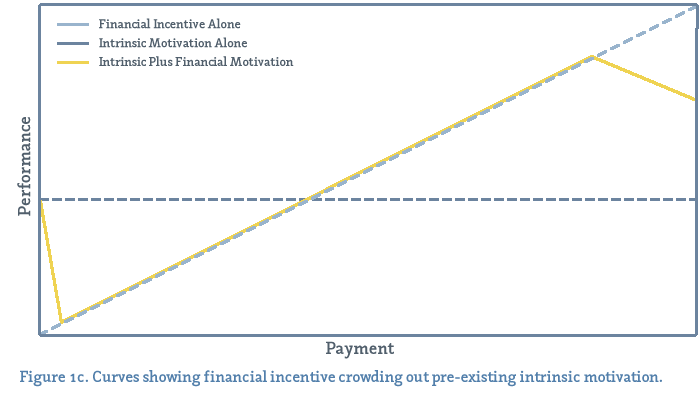

“Researchers have failed to demonstrate that financial incentives can improve patient outcomes, and not for lack of trying,” wrote Steffie Woolhandler and Dan Ariely in their Health Affairs blog.

“Reviews of early, mostly small P4P studies found virtually no evidence of global quality improvement; mixed evidence on improvement on incentivized process-based measures; and occasional unintended harms.”

The article included graphs showing that even with financial incentives, some evidence showed a temporary increase in performance followed by a plateau.

Health Affairs blog

The article went on to note, though, that no definitive studies have been conducted on pay-for-performance’s effectiveness in improving patient outcomes.

Community Behavioral Health is limited in its ability to encourage a more holistic approach because of those services that Medicaid doesn’t cover. Medicaid currently doesn’t cover more proactive services like alcohol prevention programming, mental illness treatment and Health Affairs blog The article went on to note, though, that no definitive studies have been conducted on pay-for-performance’s effectiveness in improving patient outcomes. A 2008 study in Psychiatric Services was optimistic about pay for performance as one tool among many in improving outcomes for patients and lowering costs but concluded that it alone would not be a magic bullet.

“Although pay-for-performance programs hold great promise for advancing the overall performance of the U.S. health care system, more comprehensive, systematic research is required in order to determine the desirability of using this approach in the context of behavioral health care,” the study found.

Most, though, acknowledge that pay-for-performance makes intuitive sense and that some sort of evaluation should be applied to behavioral health care. At the very least, Wilush said, pay for performance offers a snapshot of an organization’s effectiveness.

“You have to have something to measure and sometimes the measurement criteria aren’t fair to everybody, but that doesn’t mean don’t measure stuff. That’s what I think CBH is trying to do, constantly refining the performance standards.”

LOOKING AHEAD

Matthew Hurford looks forward to a time when a person’s medical treatment, mental health therapy and social services aren’t separate and distinct. A patient’s doctor, therapist and social worker, along with other service providers, would receive the greatest rewards not based on specific treatments provided but on results. The greatest profits would come when they worked synergistically to ensure that the patient was living a healthy, productive and rewarding life. That’s a vision some believe could become a reality, and one of the steps in bringing it about is a pay-for-performance model being implemented in Philadelphia in the world of behavioral health.

Dramatic changes are coming to Medicaid. The Affordable Care Act is poised to expand Medicaid eligibility to anyone earning up to 138 percent of the poverty level by 2014. That could mean an additional 78,000 to 100,000 people in Philadelphia would become eligible for Medicaid. The federal government would cover 100 percent of those new costs for the first three years of the expansion and would cover 90 percent of the costs thereafter.

Hurford said that more money alone won’t change the way CBH uses pay-for-performance models. More relevant is whether Pennsylvania becomes more supportive of some of the other innovative payment models permissible under the Affordable Care Act.

“That would have a more profound effect on delivering care, to have the opportunity to provide more care,” he said.

Jason Laughlin is a 2013 graduate of the Fels School at the University of Pennsylvania. He works as the spokesman for the Camden County Prosecutor's Office in New Jersey. He moved to Philadelphia from Concord, New Hampshire in 1999.

Works Cited

Auffarth, I., Busse, R., Dietrich, D., & Emrich, H. (2008).

Length of psychiatric inpatient stay: Comparison of mental health care outlining a case mix from a hospital in Germany and the United States of America, German Journal of Psychiatry.

Bailit Health Purchasing. 2007.

The Feasibility and Cost Effectiveness of Making Pay-for-Performance Opportunities Available to Texas Medicaid Providers.

AsRequired By S.B 10, 80th Legislature, Regular Session.

Submitted to the TexasHealth and Human ServicesCommission, December 2008.

Bremer, R. W., Scholle, S. H., Keyser, D., Houtsinger, J. V., & Pincus, H. A. (2008) .

Pay for performance in behavioral health.

Psychiatric Services, 59 (12):1419–1429. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.12.1419

J. James. (2012, October 11). Pay-for-performance. [Health Affairs Web log post].

Retrieved from www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=78

Stensland, M., Watson, P. R., Grazier, K. L. (2012).

An examination of costs, charges, and payments for inpatient psychiatric treatment in community hospitals.

Psychiatric Services, 63 (7):666–671. doi: 10.1176/appi.pa.201100402

S. Woolhandler, & Ariely, D. (2012, October 11).

Will pay for performance backfire? Insights from behavioral economics. [Health Affairs Web log post].

Retrieved from www.healthaffairs.org/blog/2012/10/11/will-pay-for-performance-backfire-insights-from-behavior-economics