A GIS analysis of children’s population health needs and resources in Philadelphia

Summary

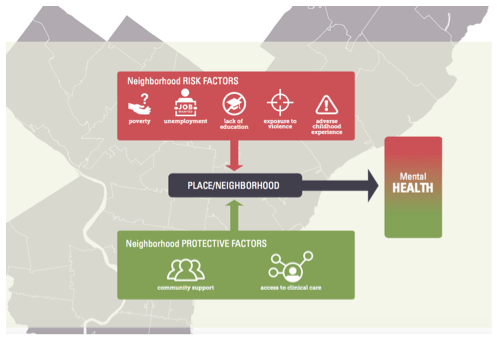

Neighborhood-level traits such as poverty, lower education, and high crime are linked with worse mental health outcomes. Social capital, such as neighbors that watch out for each other, can protect against the negative impact of neighborhood deterioration. Less is known about how perceived neighborhood trust and safety protects against mental illness. This project uses statistical and spatial (mapping) analyses to better understand the impact of changeable neighborhood characteristics on mental health, and proposes a way to use population-level risk factors to assess service need and adequacy of community resources.

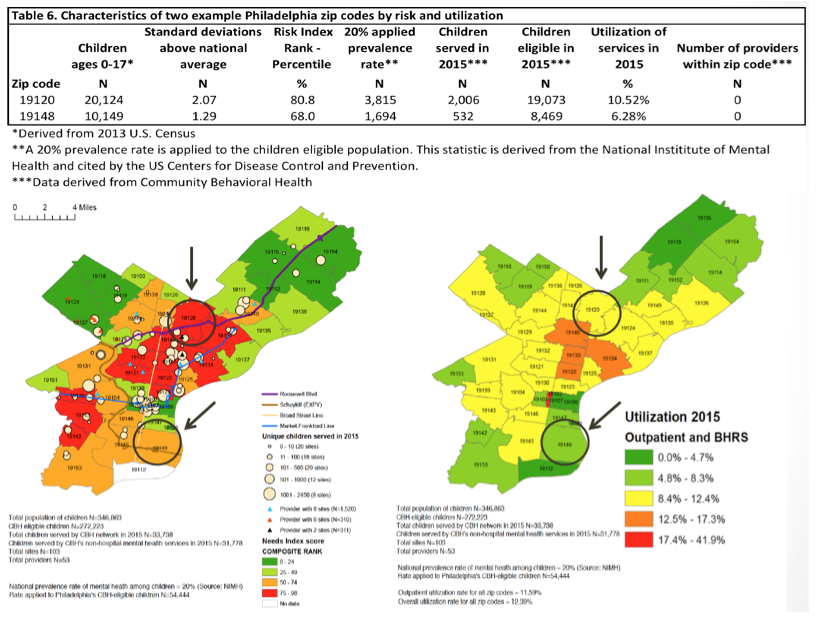

Statistical analysis (multivariate logistic regression) used data from the 2013 Philadelphia Expanded Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Survey to test the impact of perceived neighborhood trust and safety during childhood, witnessing violence during childhood, and overall adverse childhood experiences on the reported mental health of Philadelphia adults. A secondary GIS analysis used zip code-level Census, crime, and ACE data to calculate multifactorial risk index scores to identify areas of higher need. The risk index was used to compare location and utilization of outpatient mental health services available to Philadelphia’s Medicaid-eligible children ages 0 to 17 years.

Findings

Increased exposure to violence and conventional adverse childhood experiences (for instance, experiences of child abuse and neglect) were found to be positively associated with negative mental health outcomes, and social support/safety showed a protective trend against it. Meaning, the more adversity experienced the more likely it is that an adult reports negative mental health. And, the more social support/safety reported, the less likely it is that an adult reports negative mental health.

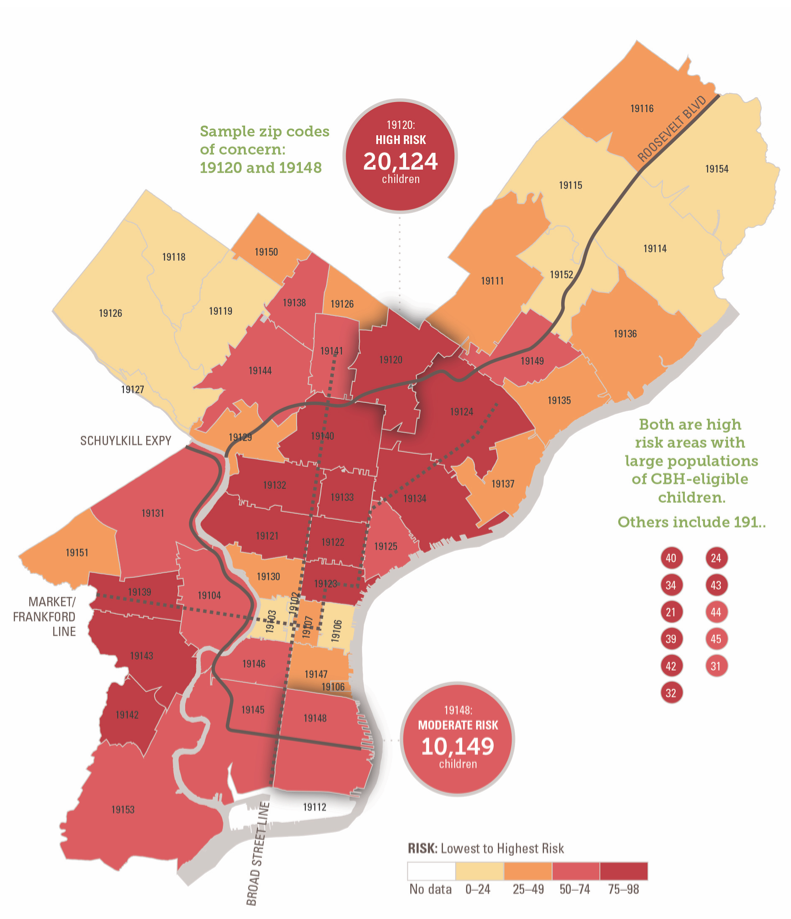

There is large variability in risk across Philadelphia. There are also areas of the city where more children live than others. There are specific zip codes with higher risk that have the highest numbers of children. This suggests a need for additional city and community resources to increase protective assets in these neighborhoods. Results build on previous research about changeable neighborhood characteristics and recommend that population health approaches be integrated to inform policy and build out more efficient and effective networks of care based on the following conceptual model:

Where are the high risk areas?

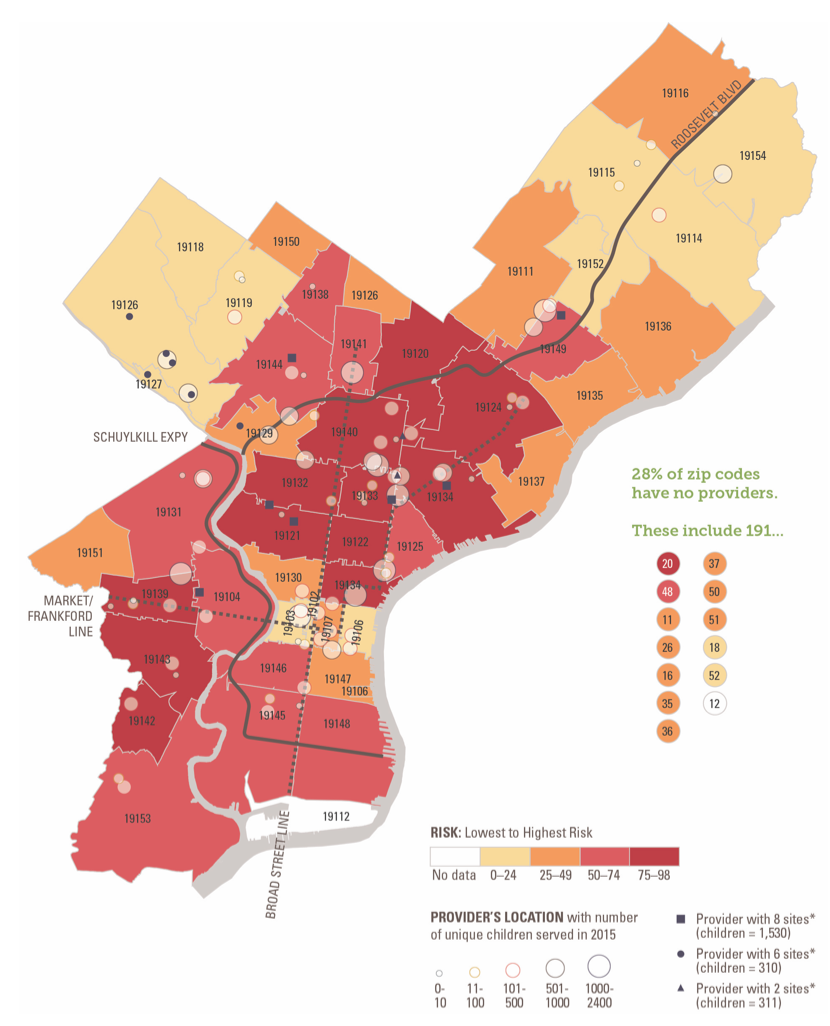

Where are the behavioral health providers located?

Some key points:

- Of Philadelphia’s 46 zip codes, 39 (85%) fall above national average for need, and 7 (15%) fall below national average for need.

- Five of the seven zip codes in the 25th-highest percentile for risk also have the highest numbers of children in Philadelphia and large percentages of Medicaid-eligible children.

- Some zip codes with moderate to high need have little to no non-hospital mental health service providers.

Below shows an example of two zip codes of concern, both of which are high in risk with large populations of Community Behavioral Health (CBH) eligible children, and neither has any outpatient providers in the CBH network of care.

Recommendations

- Increase and align the capacity of the behavioral health network according to risk and population;

- Adopt population health approaches to better understand neighborhood risk factors and the unevenness across Philadelphia;

- Use data-driven research to inform decisions on where to locate resources to increase neighborhood protective assets where they are most needed;

- Continue using data and cross-sector collaboration to better understand the city’s evolving population and needs; and

- Use the risk index to determine need as it relates to the location of other community resources like libraries, playgrounds, and physical health providers.

The ability to better understand the city from a population level allows policymakers to work toward increasing protective assets in areas that have higher risk for adverse health. Decisions driven by evidence and data, rather than instinct, would ensure a thoughtful and systematic approach to meeting the city’s needs. It can strengthen the network so that the city can move beyond compliance and serve as a model for effective and efficient care for its most vulnerable citizens.

By Quan Truong, and Samantha Matlin, PhD, Thomas Scattergood Behavioral Health Foundation in Partnership with the City of Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services

To review the full report please visit www.scattergoodfoundation.org/placemattersreport

Author bios

Quan Truong is currently a research associate with the PAMF Research Institute in the San Francisco Bay Area in California. Quan graduated with a Master of Public Health (MPH) from Drexel University in Philadelphia, with a concentration in epidemiology. Her master’s research focused on the impact of neighborhood characteristics on mental health and an evaluation of Philadelphia’s behavioral health network for children. She was awarded a HHS grant and two rounds of HRSA Urban Solutions funding for her graduate work in public health shortage areas. She was also the recipient of a Drexel University award for best epidemiology master’s project. She has a deep interest in health disparities and access to care. Prior to her work in public health, Quan worked as a journalist for the Chicago Tribune, Columbus Dispatch, and Cincinnati Enquirer, covering a number of areas related to government, politics, community, and crime. She also holds a BA in journalism and sociology from Miami University of Ohio.

Dr. Samantha Matlin, a clinical/community psychologist, is the Director of Evaluation and Community Impact at the Thomas Scattergood Behavioral Health Foundation and an Assistant Clinical Professor at the Yale University School of Medicine and an evaluation consultant at The Consultation Center. In her role, she provides training and consultation to build evaluation capacity in community-based organizations and city and state agencies. She is currently working with the Pottstown School District in their trauma-informed community initiative. She is the former Special Advisor to the Commissioner at the City of Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services where she contributed to the formulation of high priority programmatic initiatives and policy across the behavioral health system. She is committed to learning how contextual factors (such as neighborhood support, violence, trauma, and poverty) contribute to health and the interventions we can do to improve the health status of communities.