In 2012, the World Innovation Summit on Education (WISE) sponsored a team from Innovation Unit to visit sites of radical innovation in education for work (Hannon, Gillinson and Shanks 2013). The 15 chosen sites had been identified as places that were pioneering new approaches to the challenge of preparing people for work in the 21st century. The sites ranged from a radio program providing a hub for microfinance and apprenticeship opportunities in rural Nigeria to a corporate university in Mysore, India, where the IT services company Infosys trains 20,000 incoming employees a year at its Global Education Centre.

Education for work typically focuses on the problem of skills matching: there are surplus jobs requiring higher-order skills or expertise in the areas of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), while surplus workers unfit for these jobs remain unemployed. Skills matching – the process of identifying the skills needed by a particular industry and employer, and preparing learners accordingly – is an important task for vocational education, yet as numerous education scholars now argue, it is insufficient as a sole focus (Zhao 2012; Wagner 2012). Innovation expert Charlie Leadbeater recently captured this argument with the words: “The new mission of schools should be to prepare children to work in jobs that do not exist, to solve problems that are not yet apparent, using technologies that are still to be invented” (Mulgan and Leadbeater 2013, 46).

As a result, ‘problem solving’ has climbed high on the list of desirable outcomes of education. Looking across our cases, however, we saw programs designed to prepare learners not only to solve problems, but to find new problems. In other words, to be entrepreneurial and create possibilities for new work and new worlds.

This kind of preparation has been the focus of a new initiative launched by Omnia, a 10,000 student-strong institution for Vocational Education and Training (VET) in Espoo, Finland. Omnia is one of the schools responsible for a recent rise in Finland in young people’s interest in vocational education. It has gone from being the second-tier choice for 'less academic' students to a respectable career path, with the number of students listing Omnia as their first choice for upper-secondary education increasing from 1,500 to 2,300 in just four years.

Not complacent in its success, Omnia continues to innovate. In 2011, an internal team launched InnoOmnia, a center dedicated to innovating courses across the institution and developing new programs and solutions to particular educational challenges. To create a new kind of educational experience, InnoOmnia has developed into an entrepreneurial hub, bringing businesses into the college site, mixing a VET training center with startup spaces. The result is a thoroughly stimulating environment where formal and informal learning, real-world problem solving and training for skills-matching all merge. Students at the InnoOmnia space develop their own need for learning as they pursue startup plans, testing their ideas and their new skills simultaneously in a supportive environment.

In a fast-changing world, it is important that young people are given space to develop the capacity to seek new knowledge and skills. The aim is not only to prepare them for a lifetime of constant, minor skills-updates, but to create the disposition toward entrepreneurship that is demonstrably the biggest contributor to the creation of new jobs (Stangler and Litan 2009).

A necessary part of this more open-ended form of learning is the opportunity to engage with the complexity and unknown opportunities of the ‘real world’. This is difficult for formal education: the world at large is hard to package into 50-minute classes or week-long modules. Yet institutions willing to break away from these strictures have found it offers hugely engaging and powerful learning opportunities.

At the Met, the founding school of a chain to be established by the nonprofit Big Picture Learning in 1995 in Providence, Rhode Island, students spend two days a week outside of the classroom working in internships. Each student is supported to find a mentor in a particular industry who oversees their internship and helps ensure it is a very real learning experience. The number of internships which students take may vary; what does not vary is the design which enables the internship experience to be an integrated aspect of a student’s learning program.

The Big Picture schools illustrate that the function of creating possibility does not supplant those of generating solutions and skill building, but instead builds on them. A foundational entrepreneurship course (E101) equips students with the basics of financial and operational management. Those looking to take an idea further can enroll in E360, in which every course member develops and launches a startup business.

It is not only practical considerations that pose difficulties for institutions trying to make authentic learning a part of their programs. Open-ended learning is rare in systems that place a high value on standardized qualifications and accreditation, which naturally drive toward pre-determined outcome goals. While the impulse toward quality assurance and democratic accountability is entirely commendable, it becomes self-defeating if it kills off the kind of education which drives meaningful job growth.

Where can we derive accountability and quality assurance if not from standardized measures? The answer might come from looking toward some of the more unusual examples of entrepreneurship and vocational education that have caught the eye of WISE.

The Widow's Alliance Network (WANE) was started in 2007 by Akumaa Mama Zimbi, a foundation head and radio host in Accra, Ghana. Mama Zimbi was moved to act in response to texts she would receive from listeners of her show who told of the persecution and isolation they faced in Ghana as women whose husbands had died - something they were, through tradition, blamed for. The network was originally an amorphous movement aimed at making visible the plight of these women, but Mama Zimbi has developed it into a way to help widows become financially self-reliant. WANE supports local widows’ groups to identify opportunities for small businesses that might be viable in their area, and provides them with startup funds and the necessary education to make them possible. “We are not interested in education in theory,” Mama Zimbi says, “there has to be an avenue to practice for it to have impact.”

Education for work purposes (otherwise known as vocational education) has always been second tier to its academic neighbor – ‘higher learning’ – but in this unexpected context of widowhood it gains a new creativity and nobility. Rather than talk about education for entrepreneurship as another instrumental process in an already overly-mechanized system, we can talk about something broader. The starting point of a powerful and successful education for work is a sense of mission. The innovators we saw had each discovered some purpose - sometimes in unexpected places - and it was this which provided the true north around which they designed an education for their 'students' –be they Ghanaian widows or Finnish entrepreneurs.

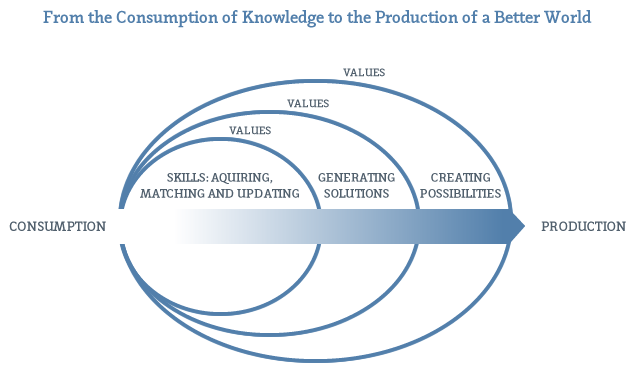

The diagram below illustrates the model of the programs we observed: skills-matching forms the basis of all these programs, but it is achieved in the context of developing more general problem-solving capabilities and the capacity to see new possibilities. A drive toward developing learner agency and a set of shared values frame the environment and provide the structure and stability in each program that allows it to innovate and evolve to meet emerging needs.

Each of these sites of innovation was certainly still in a process of evolution, developing new programs or adapting their offer to new and different students. They could do this because they were not defined by a curriculum or model, but by a commitment to a set of values, shared by founders, teachers and learners alike. Just as WANE works toward a different set of conditions with each new group of widows, another of our United States cases, the Rising Sun Center in San Francisco, also provides a diverse and evolving set of programs for a range of local needs. This includes the California Youth Energy Services, a summer program which trains young people to be paid to deliver house assessments and retrofitting, as well as a social enterprise run by the organization, which offers young people and adults the opportunity to learn about working in a small business in the emerging green energy sector.

The reason we have no simple model of successful education for entrepreneurship is that there is no one ‘best practice’ or ideal model. The powerful feature is something in the head and hearts of each educator and learner in the environment – a shared sense of mission and commitment towards a larger goal or challenge. Fostering this kind of activity at a system level is a major design challenge in itself. As we work toward it, we can draw attention to the bright spots that have already emerged and recommend four key ‘planks’ for building policy to stimulate further emergence:

- Be open to new entrants as providers

- Create incentives for organizations to work to the triple-bottom line (people, planet and profit)

- Act as a broker – connect organizations who might otherwise struggle

- Work to create blended financing models

Amelia Peterson is a Researcher with Innovation Unit and at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. With Innovation Unit, she works with the Global Education Leaders’ Program, and was one of the authors of a book about the program’s work, Redesigning Education: Shaping Learning Systems Around the Globe.

Valerie Hannon was a founding director of Innovation Unit when it was initially established within government, and subsequently became its first Managing Partner when IU became an independent nonprofit. Amongst her recent work, she authored the 2012 WISE book, Learning a Living: Radical Innovation in Education for Work.

References

Hannon, Valerie, Sarah Gillinson and Leonie Shanks. 2013. Learning a Living: Radical Innovation in Education for Work. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Mulgan, Geoff and Charlie Leadbeater. 2013. Joined Up Innovation: what is systemic innovation and how can it be done effectively? London: Nesta

http://www.nesta.org.uk/library/documents/Systemsinnovationv8.pdf

Stangler, Dane and Robert E. Litan. 2009. ‘Where Will All the Jobs Come From?’ Kaufman Foundation Research Series: Firm Formation and Economic Growth. Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. http://www.kauffman.org/uploadedFiles/where_will_the_jobs_come_from.pdf

Wagner, Tony. 2012. Creating Innovators: the Making of Young People Who Will Change the World. New York: Scribner.

Zhao, Yong. 2012. World Class Learners: Education Creative and Entrepreneurial Students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Books.