Overview of Social Problem

Many students with disabilities display behaviors that are considered “inappropriate” in many schools. These problem behaviors are often the reason a student receives special education services or are removed from their home school. The Individual with Disabilities Education Act (2004) requires educators to complete a functional behavior assessment (FBA) and Positive Behavior Support Plan (PBSP) when a student demonstrates problem behavior. Specifically, the FBA is designed to help determine the underlying function or purpose of behavior. Keep in mind, that all student behavior is purposeful and goal-oriented. Although some problem behaviors maybe socially undesirable, from a student’s perspective they serve a function or purpose. In contrast to typical intervention efforts, the “function” of the student’s behavior is more critical than its “form.”

Historically, a behavior plan would primarily focus on decreasing problem behaviors with little emphasis on the purpose or function of the behavior. Moreover, many behavioral intervention plans were developed without trying to identify and teach prosocial behaviors to the student. However, intervention plans are unlikely to achieve long term success if they do not directly address these two issues. In fact, a problem behavior will often return unless an intervention plan addresses the underlying function of the problem behavior and appropriately identifies an alternative behavior or replacement skill. Both aspects of an intervention plan can be accomplished by using a competing behavioral pathway model.

Competing Behavior Pathway Model

The competing behavior pathway model provides a link between the FBA and the developing PBSP. The model is based on the logic that many different behaviors may serve the same function (e.g., produce the same reinforcing event). The likelihood that a person will use the alternative behavior in the future increases when a positive alternative behavior (e.g., replacement skill) provides the same type of consequence as the problem behavior. Thus, the competing behavior pathway helps to design a multi-component PBSP that identifies competing behavioral alternatives (i.e. Replacement Behavior) to the Target Behavior and determine strategies for making the Target Behavior ineffective, inefficient, or irrelevant through changes to the routine or environment (Crone & Horner, 2003). Stated differently, the basic idea in developing a PBSP based on the competing behaviors model is to make problem behaviors:

- irrelevant (there is no need to do them);

- inefficient (there are easier behaviors to engage in); and

- ineffective (problem behaviors no longer work to produce the desired outcome).

Identifying the Functions of Challenging Behavior:

The competing behavior pathway model involves multiple steps that begin with the completion of an FBA. The primary goal is to determine the function of the problem behavior by examining the variables in the environment. Over the past 30 years, researchers have identified four categories of possible functions for problem behaviors (see Table 1 below). The function of a challenging behavior helps determine what conditions are maintaining or reinforcing a behavior. In fact, challenging behaviors are learned and shaped by reinforcement. A student will continue to repeat the behavior when it is positively reinforced and will likely demonstrate the same behavior when faced with similar conditions in the future. When a behavior is positively reinforced, something in the environment is added that increases a response (attention or access to something). Whereas, negative reinforcement is when a certain stimulus/item is removed after a particular behavior is exhibited. The probability of the particular behavior occurring again in the future is increased because of removing/avoiding the negative stimuli. For negative reinforcement, taking something negative away which increases a response (allows escape from something). Typically, the four functions associated with problem behaviors are 1.) attention, 2.) access, 3.) sensory stimulation, and 4.) multiple functions.

When challenging, behaviors are positively reinforced, they continue to occur or be maintained by gaining access to attention, tangibles, or sensory stimulation. So, the first step in addressing a student’s behavior is to systematically examine the variables that influence their interactions within the environment during the FBA. Specifically, the antecedent-behavior-consequence (A-B-C) to relate to the problem behavior are analyzed to develop an initial hypotheses or summary statement that identifies what the individuals “gets” or “avoids” as a result of the behavior (Nelson, Roberts & Smith, 1998; Roberts, Marshall, Nelson, & Albers, 2001).

Competing Behavior Model Pathway:

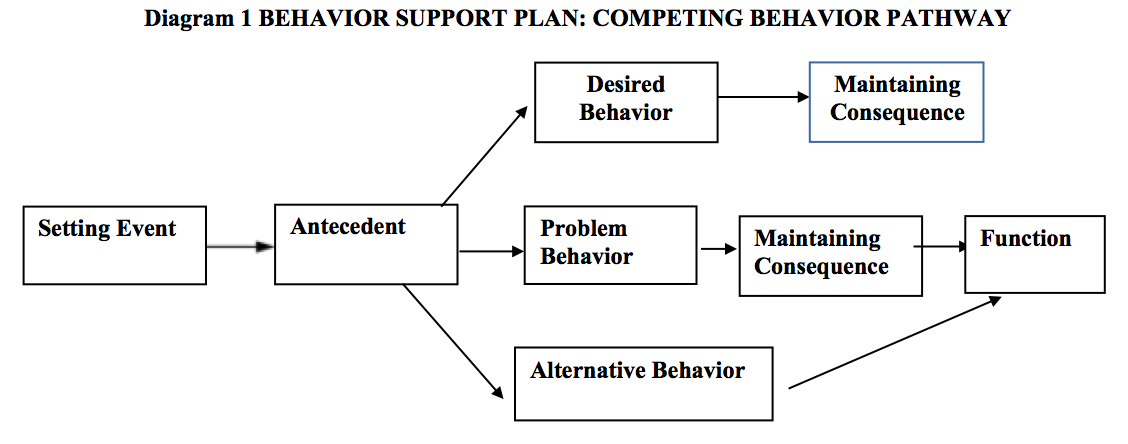

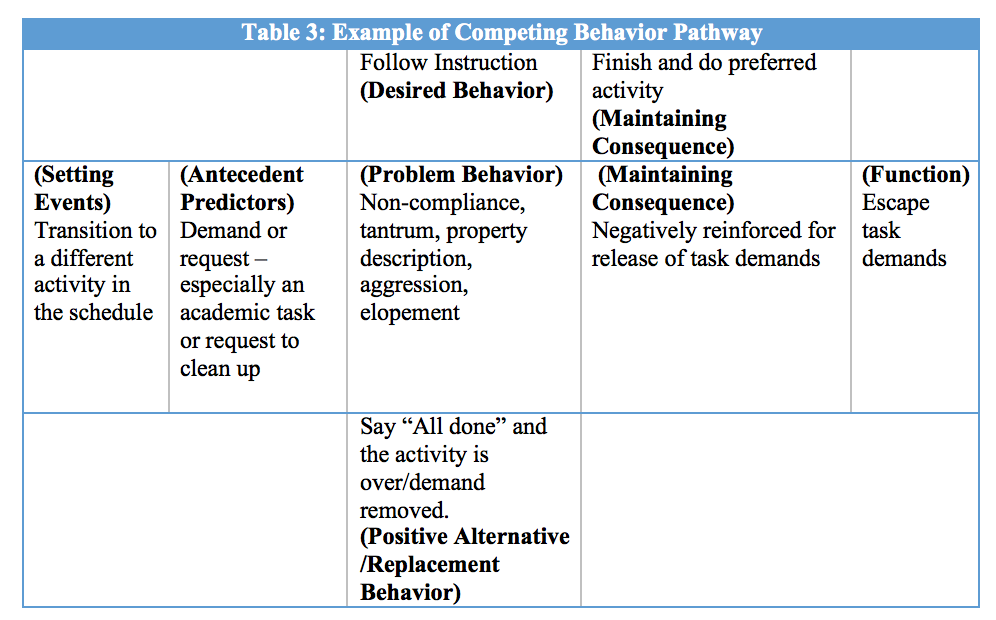

Based on the FBA, four pieces of information should be identified for the competing behavior pathway model as follows: 1.) a definition of the problem behaviors, 2.) identification of the predictor events (immediate antecedents) for problem behaviors, 3.) determination of the maintaining consequence of problem behaviors, and 4.) identification of the setting events relevant to occurrence of problem behaviors. Collectively, these four pieces of information are put together in a summary statement (or hypothesis) regarding the problem behavior that is derived from the FBA. After the FBA summary statement is completed the educational team should determine 5.) the desired behavior in the situation (i.e. what behavior(s) do you really want the person to do?), 6.) the maintaining consequence for the desired behavior, and 7.) the positive alternative behavior (e.g., replacement skill) that will produce the same maintaining consequence as problem behavior (Horner, Sugai, Todd, & Lewis-Palmer, 2000; McIntyre, (n.d.). The Diagram 1 represented below provides a guiding template for the competing behavior pathway and Table 3 provides an example of how this model looks when completed.

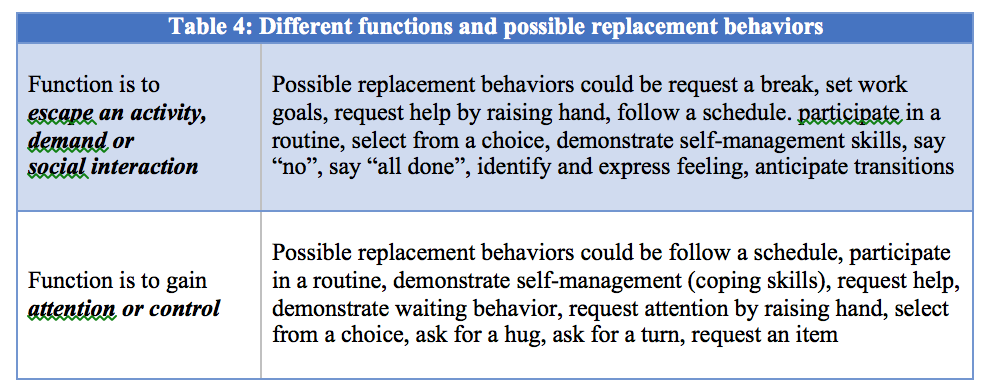

Description of Replacement Behaviors: As you can see in the example above, a replacement skill is an appropriate skill that is maintained by the same consequences as the challenging behavior. Replacement skills are important because they help the individual meet a need in a more suitable way. A replacement behavior also represents the behavior you want to occur instead of the unwanted target behavior (e.g., aggression, destructive behavior, self-injury, or tantrums). For example, what if a student engages in pulling out hair when faced with difficult situations and the function of behavior is negative automatic reinforcement to relieve anxiety. Behavior plans can include response blocking or removal of rewards (e.g., token board) to decrease the behavior. However, while that behavior may decrease, another behavior may pop-up that provides the automatic reinforcement of relieving the anxiety if need for that reinforcement is not addressed. So, the team needs to think about ways the student can access that automatic reinforcement via an alternative behavior or replacement skill in order to truly make a difference for the individual.

Important Considerations When Selecting a Replacement Skill

When selecting replacement skills, there are a few guidelines the team should consider. First, a replacement behavior should be something a student can do or can learn to do. Second, it is important to realize that the more efficient and effective the replacement skill, the more likely it will be used in favor of the challenging behavior. In other words, the replacement behavior should have the same qualities of the challenging behavior. For example, if the student currently has tantrums in order to get attention from the teacher, the student must have a way to gain the same results from the person he/she desires attention from. The replacement skills should always require less effort to produce than the problem behavior. Third, the rewards for engaging in the more appropriate replacement skill should be far greater than that which the student receives for exhibiting challenging behavior. When these conditions occur, the replacement skill will be more likely to increase or used compared to the challenging behaviors (Carr & Durand, 1985). For this reason, the replacement behavior needs to be more efficient than the challenging behavior at accessing the reinforcement.

There are generally three elements that make up efficiency. The replacement behavior has to get the reinforcement (e.g., attention, escape, automatic reinforcement) faster, easier, and more reliably. We can accomplish efficiency of the replacement behavior through the choices we make about the form of behavior we decide to teach as well as about differentiating our response to them (e.g., delay reinforcement for the challenging behavior while reinforcing each instance of the replacement behavior immediately and every time). So, if a tantrum behavior gets the student out of work immediately (i.e., faster) but asking for a break requires the student to do two more problems, then it is less efficient than the challenging behavior and won’t be used to replace it.

Likewise, if it’s easier to hit someone as opposed to searching for the correct vocabulary word in a communication device to tell the teacher what they want, then hitting is going to prevail. Furthermore, the replacement behavior has to get reinforcement more frequently and more consistently than the challenging behavior. To accomplish this, we need to make sure that the replacement behavior is something that is easily understood and will get the needed response in most situations. If we are teaching a student to ask for attention and the student does so using an idiosyncratic method that is not easily understood by others, then the replacement behavior will not be understood and reinforced across environments. In general, replacement skills must be relevant to the child's unique situation, abilities, and must be an immediately efficient method for communicating wants and needs (see Table 4 for examples).

Effectiveness of PBSP

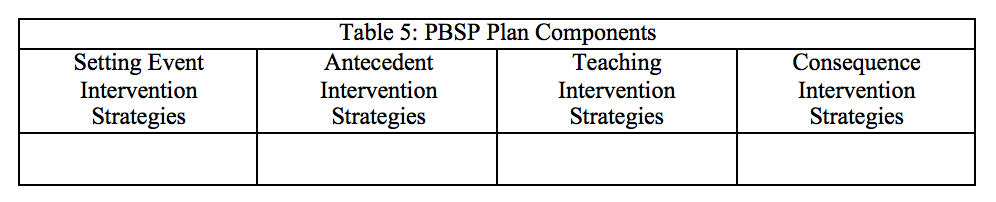

After the competing behavior pathway is completed, the team outlines and finalizes a PBSP that includes interventions for setting events, antecedents, teacher and consequence interventions. The setting and antecedent strategies focus on prevention of the problem behavior. These pieces of the plan explain how staff will adapt the environment to reduce or eliminate setting events and antecedents that trigger the problem behavior. Examples of these strategies could include classroom management techniques, accommodations and modifications to work, visual strategies, or sensory diets. The teaching strategies focus on what skills can be taught to the student to replace or meet the same function as the students target behavior. Lastly, the consequences strategies focus on how staff will respond effectively and consistently in order to support positive behavior and reduce the intensity and frequency of the target behavior (See Table 5).

What follows is an example of a PBSP and its related components. The plan is based on the competing pathway example found in Table 3.

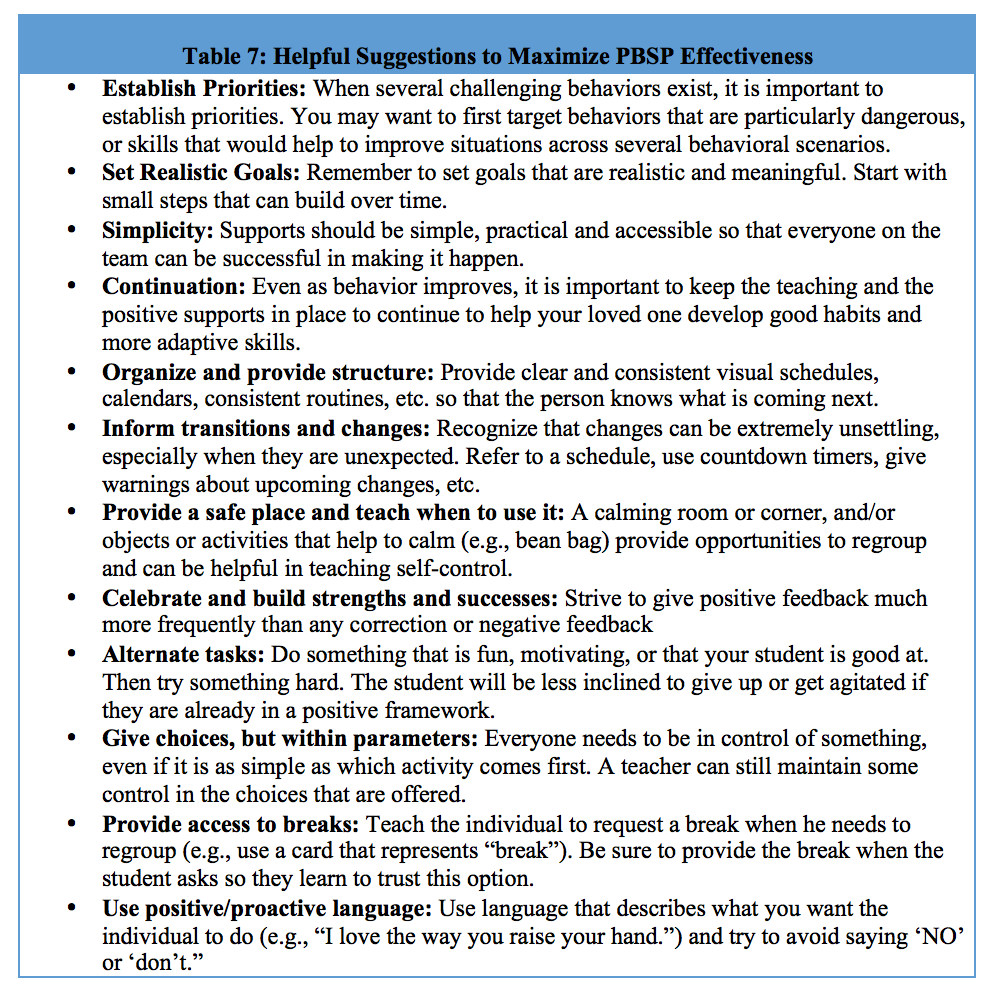

Once the PBSP is developed, it is important to monitor the effectiveness of the plan. This should include measuring the problem behavior as well as the replacement behavior. Additionally, it is important to monitor if the plan is being implemented as intended (e.g., treatment fidelity/ integrity). PBSP data should be graphed and compared against baseline data to determine the effectiveness of the plan. The use of the replacement skills should be documented to determine if students are learning the skill and if the behavior is maintained over time and/or across settings. If minimal progress is made in decreasing challenging behaviors, increasing replacement skills, the behavior support plan should be reevaluated and refined to improve the effectiveness of the plan (See Table 7). Consequently, the development of the FBA and PBSP should not be viewed as a static event but rather as an ongoing process that is conducted on an ongoing basis to revise the PBSP or address new behavioral concerns.

Behavior is a form of communication that serves a purpose. As educators, we need to teach and reinforce the behaviors we want to see in the classroom. Educators should use the competing behavior pathway model to identify the purpose (function) of behavior and collaboratively develop a PBSP that focus on teaching replacement behaviors in a pro-social manner. In turn, a PBSP that includes setting, antecedent, replacement behavior, and consequence strategies can provide a comprehensive and multi-faceted plan that moves beyond the goal of only reducing problem behaviors by providing a powerful and positive plan that can change a student's life.

Works Cited

Carr, E. G., & Durand, V. M. (1985). Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18(2), 111-126.

Crone, D. A., & Horner, R. H. (2003). Building Positive Behavior Support Systems in Schools; Functional Behavioral Assessment. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Horner, R. H., Sugai, g., Todd, A. W., & Lewis-Palmer, T. (2000). Elements of behavioral support plans: A technical brief. Exceptionality, 8(3), 205-216.

McIntyre, T. (n.d.). Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA). Retrieved from http://www.behavioradvisor.com/FBA.html.

Nelson, J. Ron; Roberts, Maura L.; Smith, Deborah J. (1998) Conducting Functional Behavioral Assessments: A Practical Guide. Sopris West, 4093 Specialty Place, Longmont, CO 80504.

Roberts, M. L., Marshall, J., Nelson, J.R., & Albers, C. A. (2001) Curriculum-based assessment procedures embedded within functional behavioral assessments: Identifying escape-motivated behaviors in a general education classroom. School Psychology Review, 30 (2), 264-277.