Abstract:

After a little more than a decade and considerable achievements, Ashoka Social Financial Services (SFS) decided it was time to redefine success.

As the pace of change is accelerating exponentially, we all face a new set of historic opportunities, and SFS believes success requires trying to live up to the historic moment.

This short piece describes how this new definition of success led SFS to question its assumptions and eventually move away from social business, social enterprise and impact investing and towards a new approach called Economic Architecture.

This piece also introduces the basic motivation behind Economic Architecture and suggests that it has the potential to harness the power of the whole market to improve the character and quality of people’s lives. And it indicates how SFS will continue to develop the idea going forward.

When I recently returned to full-time leadership of Ashoka’s Social Financial Services program, I had the opportunity to take a fresh look at our work.

Our program was just over one decade old. In that time, we have identified and supported dozens of leading social entrepreneurs, many of whom have become points of reference in the emerging social finance space, and have collectively impacted over 50 million people. We have also worked to pioneer new financing vehicles and created innovative partnerships that have mobilized over half $1 billion. By many measures, including those we had set for ourselves, Ashoka Social Financial Services was a success. But we realized it was time for us to change our definition of success.

We are living in a time defined by change. As the rate of change accelerates exponentially, it creates historic opportunities to address long-standing problems and a dire urgency to act now. Success, we believe, requires trying to live up to this historic moment. And that means being willing to question everything we’ve done and starting over. So we wound down our existing program and challenged ourselves to develop a new approach.

We started with a focus on the market, because we believe the market is the most powerful tool we have to improve the quality and character of people’s lives. As a result, we believe success requires harnessing the power of the market effectively to create impact. The question for us was: How?

We have learned many lessons on how to do this from social business, social enterprise and impact investing, but ultimately we decided we needed to move away from each of these approaches because they are inherently limited by their focus on the small portion of the market that is not solely motivated by the pursuit of profit.

Success requires pushing beyond this limitation and seeking to engage all of the market, regardless of people’s motivations. To gain a clearer understanding of what this would require, we needed to also better understand of what we were trying to create, i.e., how does the market create impact, and how we could shift the market so more of that happened?

As we looked across the sector, we found that many initiatives reflect a traditional view according to which creating wealth is the primary means by which the market improves people's lives.

It's not a surprise then that these initiatives tended to focus on enhancing the market’s ability to create wealth. And their approaches tend to fall into one or more of four broad categories. They ask:

- How can we stimulate the creation of wealth (Growth)?

- How can we increase the number of people participating in the creation of wealth (Access)?

- How can we make sure people are obeying the rules (Enforcement)?

- How can we compensate those who have not benefited from the wealth creation (Redistribution)?

In contrast, as we looked at the work of leading social entrepreneurs on the ground around the world, a different view of the market started to come into focus. On this view, the market is the largest coordinating mechanism in society. It is the mechanism we use to decide what is important, who is going to do what, and to what extent each person will benefit.

This suggests a very different set of evaluative and remedial questions. For example:

- Does the market place value on things that are actually valuable? How do we change what the market values?

- Does the market allocate people’s time, talents and ability to their highest and best purposes? How do we change where the market allocates people’s time, talent and abilities?

- Does the market provide benefits appropriately? How do we change the way the market provides benefits?

Cumulatively, this suggests a very different approach to harnessing the power of the market. This is not like working with social enterprises, where the focus is on creating and growing organizations to increase the number of people impacted as it scales. Nor is it like impact investing where the focus is on creating deals or new kinds of financing mechanisms. This suggests that success requires designing innovations that change the structure of the market, using its role as a coordinating mechanism to create impact.

With this goal clearly in view, we began to incubate a new Social Financial Services program based on a new approach we called Economic Architecture. Economic Architecture focuses on structural innovations that harness the power of the market to improve the quality and character of people’s lives. Once we started to realize the importance of this approach, we started to recognize examples within Ashoka’s global Fellowship of over 3,000 social entrepreneurs in over 80 countries around the world.

For example, the emergence of effective certification regimes such as FairTrade, Fairtrasa and Canopy’s Ancient Forest Friendly initiative are all illustrations of structural innovations. Instead of starting companies that employed better labor and/or environmental processes, each of these social entrepreneurs created a certification that conveyed a premium for other market participants who adopted better practices. They effectively changed what the market valued, and as a result they are changing the pattern of activity in the marketplace.

When Joaquim de Melo created Banco Palmas to stimulate economic growth in Fortaleza, he created a structural innovation. Rather than merely creating a social enterprise that offered local jobs, he created a new currency that offered preferential prices for those shopping locally. This created incentives for consumers and retailers and changed the pattern of activity across the market.

When Gautam Bharadwaj created IIMPS to create a pension system for informal workers, he was creating a structural innovation. Rather than merely creating a financial firm that offers pensions, he enabled the pension system to effectively expand to incorporate a large number of people it had previously excluded, and changed the pattern of activity in the marketplace.

There are dozens of other examples like these. They arise in industries as varied as financial services, manufacturing, financial services, healthcare, energy and others. They are beginning to appear in geographies across the world from South East Asia, to Africa, Latin America, Europe and North America. They are effective in emerging markets and developed markets.

Each of these innovations creates tremendous leverage. Understanding their effectiveness requires looking beyond the size of their organizations to the extent of the market transactions that they’ve influenced.

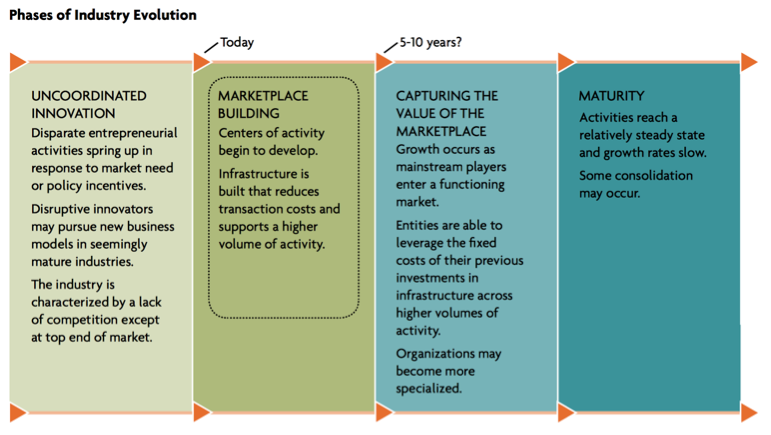

We are now approaching a critical mass of these innovations so we can begin to move beyond understanding individual examples to understanding this approach for engaging the market. Specifically, as we develop the practice of Economic Architecture, we seek to understand which issues can best be addressed by structural innovations, in which contexts are they most likely to be effective and how do we design them most effectively.

To this end we have begun to create partnerships with academics and academic institutions to develop a conceptual framework for Economic Architecture and design principles for developing structural innovations.

While this work is still in its early stages, we are encouraged by its ability to engage all of the market, not merely those who are not solely motivated by the pursuit of profit. And we are encouraged by the fact that structural innovations create impact by changing the pattern of activity in the market in ways that go far beyond merely creating wealth.

Our new Social Financial Services program is in its early days. We will continue to submit our focus on Economic Architecture to rigorous testing. Success will not only require that it enables us to identify and create innovations that address historic opportunities, but also that we are able to codify this approach so that it can be taken up and improved by others.