I can’t walk through Center City Philadelphia these days without having to cross the street several times to avoid construction projects. A twenty-six-story residential and commercial venture is rising from a former parking lot in between my morning coffee stop and the office, and in every other direction, brand new high-end apartments, condos, hotels, restaurants and retail are rising too. I don’t mind the extra steps; it’s good exercise for me and a great investment for the city. But the development boom that started in Center City, and is now spreading to surrounding neighborhoods like Point Breeze, Fishtown, Francisville and others with homes that are now selling at $400k or higher, and nationally recognized restaurants with pricey menus opening up on neighborhood commercial corridors, is like any other form of pressure: it pushes other entities away. When those entities are people and their small businesses, we’ve got gentrification.

Gentrification is about redevelopment that benefits one class of people by unfortunately sending another class packing. They may no longer be able to keep up with rising rents for their small business or apartment. Their limited incomes may not be able to absorb an increase in property taxes as a result of higher real estate assessments. Sometimes, gentrification can occur when affordable goods or services can no longer be found in a neighborhood, causing lower income residents to move.

Why should people who are interested in a stronger, healthier Philadelphia care? After all, people move all the time, and businesses come and go for a lot of reasons. But when they are pushed out of improving communities, we all lose.

A recent report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia1 used credit report data to track how people moved in and out of gentrifying neighborhoods in Philadelphia. Their research showed that when lower credit score residents (who are likely lower-income) move out of gentrifying neighborhoods, they move to neighborhoods with poorer quality of life, with lower performing schools, higher crime rates, and/or higher unemployment rates. When they were able to stay in the improving neighborhood, however; their credit scores actually boosted by an average of 11 points, a proxy for improvement in their financial health. Research2 shows that poor children who grow up in good neighborhoods have a much better chance of breaking generational cycles of poverty and becoming economically mobile later in life. So if we want to attack Philadelphia’s stubbornly high poverty rate, we must ensure that low-income people can stay in – or choose to move to – good quality neighborhoods.

A recent report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia1 used credit report data to track how people moved in and out of gentrifying neighborhoods in Philadelphia. Their research showed that when lower credit score residents (who are likely lower-income) move out of gentrifying neighborhoods, they move to neighborhoods with poorer quality of life, with lower performing schools, higher crime rates, and/or higher unemployment rates. When they were able to stay in the improving neighborhood, however; their credit scores actually boosted by an average of 11 points, a proxy for improvement in their financial health. Research2 shows that poor children who grow up in good neighborhoods have a much better chance of breaking generational cycles of poverty and becoming economically mobile later in life. So if we want to attack Philadelphia’s stubbornly high poverty rate, we must ensure that low-income people can stay in – or choose to move to – good quality neighborhoods.

When small businesses are displaced from a neighborhood, this can mean the end to the business, not just a relocation. Businesses that rely on foot-traffic or being easily accessible to public transit may not be able to survive if they are pushed out of the storefront in which they’ve figured out how to operate. That means families lose their jobs and incomes, and neighborhood residents lose access to the affordable goods and services that they provided. Alternatively, if we had tools to help those businesses stay in improving neighborhoods and benefit from the changes, their revenues could rise and provide even greater economic opportunity to their families and the city.

Meanwhile, what’s happening to the neighborhoods that are not gentrifying? They continue to struggle with high rates of poverty, vacancy, blight and crime. Their residents aren’t any better off for that multimillion-dollar development downtown, which they probably subsidized with a tax abatement or other form of public funds. Responses to gentrification should also include responses to neighborhoods that continue to be disinvested.

The answer to these challenges – and the answer to gentrification – is not less investment from the private sector. It’s more investment in the people and places that the private market is not serving, so that they can stay in improving communities or choose to move to good neighborhoods, and see their own struggling neighborhood get better. Because Philadelphia does better when we all do better, now is the time to advance policies that will leverage the positive changes occurring in some of our neighborhoods for the benefit of those who would otherwise be left out. That is Equitable Development.

To advance Equitable Development, the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations (PACDC), which represents organizations that work to revitalize neighborhoods and improve the quality of life for Philadelphians, released “Beyond Gentrification, Toward Equitable Neighborhoods: An Equitable Development Policy Platform for Philadelphia.” The Platform contains nineteen recommendations in five key areas that Mayor Kenney and City Council should advance:

1. Strengthen the Ability of Neighborhood Groups and Residents to Create Inclusive Communities: Strong neighborhoods are made up of neighbors who care about their communities and welcome new residents, as well as community-based organizations that provide a forum for input and action to create inclusive neighborhoods. Through the Philadelphia City Planning Com¬mission’s Citizens Planning Institute, community residents should be given the knowledge and tools to participate in the Registered Community Organization (RCO) process and other planning and zoning decisions in effective, inclusive ways. Nonprofit community, civic and neighborhood associations play a vital role in engaging neighborhood residents and con¬necting them to vital services and programs, yet are vastly under-resourced. The City should boost to $4 million per year its investment in Neighborhood Advisory Committees (NACs) and other neighborhood-based groups that engage the community. Market-rate development projects that receive public subsidies should be required to advance Equitable Development in a meaningful way, such as through a setting aside of affordable residential or commercial spaces.

1. Strengthen the Ability of Neighborhood Groups and Residents to Create Inclusive Communities: Strong neighborhoods are made up of neighbors who care about their communities and welcome new residents, as well as community-based organizations that provide a forum for input and action to create inclusive neighborhoods. Through the Philadelphia City Planning Com¬mission’s Citizens Planning Institute, community residents should be given the knowledge and tools to participate in the Registered Community Organization (RCO) process and other planning and zoning decisions in effective, inclusive ways. Nonprofit community, civic and neighborhood associations play a vital role in engaging neighborhood residents and con¬necting them to vital services and programs, yet are vastly under-resourced. The City should boost to $4 million per year its investment in Neighborhood Advisory Committees (NACs) and other neighborhood-based groups that engage the community. Market-rate development projects that receive public subsidies should be required to advance Equitable Development in a meaningful way, such as through a setting aside of affordable residential or commercial spaces.

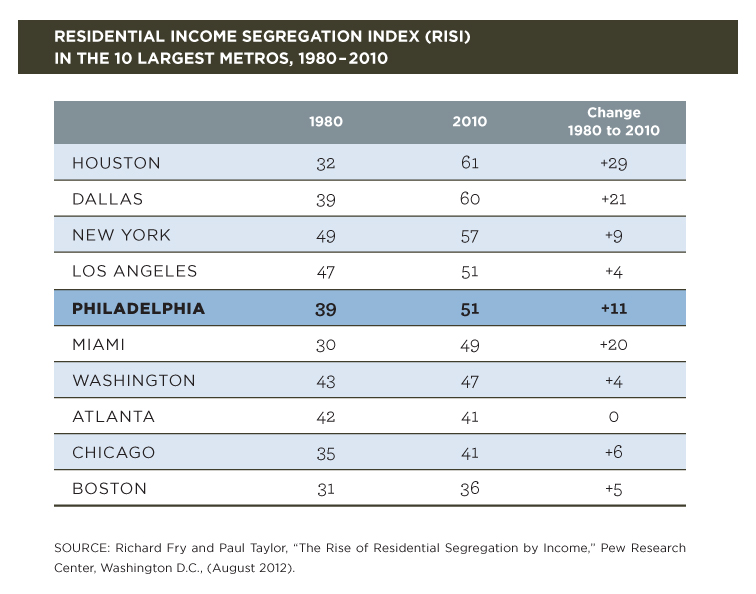

2. Create and Preserve Quality, Affordable Home Choices in Every Part of the City: Housing policies are a significant way we can attack economic segregation in Philadelphia. The Kenney Administration must lead by creating a comprehensive housing strategy to address our city’s needs for quality affordable homes, including at least doubling dedicated funding for the Philadelphia Housing Trust Fund to $25 million per year. We must boost strategies to end homelessness, build and preserve more affordable homeownership and rental homes in ev-ery part of the city, including homes that are permanently affordable, spur more market-rate development, and ensure that residents are not involuntarily displaced from the neighbor-hoods that they call home. It’s time to review the 10-Year Property Tax Abatement to determine if it must be updated for our current real estate market.

3. Expand Economic Opportunities on Our Neighborhood Corridors and Increase Local Hiring and Sourcing by Major Employers and Developers: If Center City is the heart of commerce in Philadelphia, our neighborhood commercial corridors are its economic veins. Funding for programs to improve the property conditions of stores, clean and green the corridors, organize shop owners and market corridors should be boosted to $4 million per year with a mix of local and federal funds. The City should allocate at least $1 million in local funds to leverage another $1 million from the state through the ReCLAIM program to finance mixed-use developments on our neighborhood corridors that could help small businesses and residents alike. The Philadelphia CDC Tax Credit Program, which supports neighborhood economic development, should be expanded.

The Kenney Administration should continue and improve efforts to increase hiring of Minority, Women and Disabled Owned Business Enterprises (M/W/DBEs) and workers in projects where public funds are involved by maintaining a commitment to Equal Opportunity Plans (EOPs), and should monitor closely how the expansion of EOPs to include goals for hiring of city residents is being implemented. The Mayor should also use his leadership to gain a commitment from developers and their contractors to cre¬ate EOPs and reports for large projects that are not publicly subsidized. Large employers in Philadelphia have an important role to play in advancing Equitable Development, and the Mayor should do more to bring them to the table by encouraging them to source more of their services locally, as well as prioritize hiring from the local workforce.

4. Understand the Threats and Impacts of Displacement and Expand Assistance Programs: One of the greatest fears about gentrification is involuntary displacement: long-time residents and small businesses that want to stay in their neighborhoods but can no longer afford rising rents or property taxes. There is much we don’t know about displacement: how many people does it affect and what happens to them if they are displaced? Policy makers need to collect better data to understand what’s happening in our neighborhoods and craft effective policy solutions, particularly for small businesses and residential renters for whom few protections ex¬ist. The existing measures to protect homeowners from displacement due to rising property taxes must be better promoted, and homeowners must be educated about the value of their growing asset and how to manage it in their own best interest. More can be done to help small business and residential renters to provide them with stability in improving communities, and give them more notice when rents are increasing.

5. Attack Blight, Vacancy, and Abandonment in All Neighborhoods: Decades of disinvestment in some of our neighborhoods and declining conditions in once-stable neighborhoods have created a scourge of vacant lots, abandoned buildings, and poor property conditions, harming those that chose to remain, or who can’t afford to live in more attractive, safer neighborhoods. These blighted conditions further strip wealth from neighbor¬hood property owners, as home values near vacant properties are decreased by an average of $8,000 according to a recent study.3 The City took major steps by making the Philadelphia Land Bank operational in 2015 in order to more strategically address vacant properties and get them into productive re-use more quickly, as well as improved Code enforcement on vacant properties in order to hold owners accountable to their neighbors. City Council and the Kenney Ad-ministration must maintain a strong commitment to both of these strategies, ensure that L&I has adequate resources to hold landlords accountable for poor property conditions, and help low-income homeowners become Code compliant through assistance with needed repairs.

This platform is not the answer to all of Philadelphia’s problems. Economic inequality, low wages, high poverty, high crime rates, etc., are a complex set of problems that need to be attacked at many angles. But as a network of community development corporations, this is our field’s contribution to that important work.

Since we published our platform in February 2015, progress has been made on many of these recommendations under the leadership of former Mayor Nutter, Mayor Kenney, Council President Clarke and several other City Council members. We have significant momentum at the start of 2016 to protect long-time residents and small businesses from being displaced, and encourage new development, residents and investments. We can do both, and we must, because it’s not an option to ignore the deep inequalities in income and opportunity that hold so many Philadelphians back. It holds our entire city and region back as well. Equitable Development is a pro-growth strategy focused on attacking that inequality.

PACDC’s Equitable Development Policy Platform is available at www.pacdc.org/EquitableDevelopment and organizations and individuals can endorse that platform at that address.

Beth McConnell is policy director of the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations.

References:

1. “Gentrification and Residential Mobility in Philadelphia,” Lei Ding and Eileen Divringi, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia; and Jackelyn Hwang, Princeton University. December 2015.

2. “Where is the Land of Opportunity?” Chetty, Hendren, Kline, Saez and Turner, The Equality of Opportunity Project at Harvard University. June 2014.

3. Vacant Land Management in Philadelphia: the Costs of the Current System and the Benefits of Reform (Executive Summary). By Econsult Solutions for PACDC and the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, 2010. Available at: http://www.phillylandbank.org/reports#sthash.YVMplpeV.dpuf