Introduction

Research has found that innovative and adaptive nonprofits achieve greater social impact. While we may know very little about the mechanisms driving innovation within nonprofits, this article features the case of a 145-year-old, multiservice, nonprofit agency in Philadelphia—Episcopal Community Services (ECS)—and studies how innovation can take place in a traditional nonprofit setting. From interviewing the executive director and staff, four observations were made about what drives ECS’ success: a desire to adapt and excel, being a beneficiary-centered agency, cultivating an open, innovative culture throughout the agency and institutionalizing data-driven innovation. From ECS’ approach, nonprofit leaders and managers can find practical insights for initiating and sustaining innovation in their own organizations.

Understanding the process and tactics of leading organizational change and innovation can unleash the enormous potential of nonprofits to achieve greater good and scale up their impact in a more rapid, systemic and sustainable way. It is also a realistic agenda for becoming agile, innovative agencies that better serve clients and attract capital to sustain their operations. However, we know little about the nature and process of leading and managing organizational innovation in the context of social service provision.

In the age of impact maximization, organizational innovation is highly relevant because organizations with audacious social missions are mandated by beneficiaries, donors, investors and society to go beyond improving organizational efficiency and produce quantifiable impact measures such as number of clients served, number of meals distributed, reduced overhead costs, etc. As organizational change-makers, the leaders of these agencies are driven and called upon to benefit the lives of the people that they serve and to be transparent about and accountable for their social outcomes.

In recent decades, academics and practitioners have developed many useful tactics and tools, such as logic models, the theory of change, balanced scorecards, etc., for strategic planning and performance evaluation. These tools equip nonprofits to plan ahead with more holistic perspectives and strategic steps. Although strategic plans are necessary, they are insufficient on their own as they do not automatically enable change and innovation.

First, strategic plans do not elucidate the black box of how to change and innovate. Organizations are not static but are constantly changing. Second, even though improved performance and better outcomes are articulated and imprinted in the best strategic plans, they will not be realized unless an organization actually changes and innovates. Hence, this article presents some practical lessons drawn from an innovating nonprofit in Philadelphia—Episcopal Community Services (ECS)—that other nonprofits can take advantage of to develop their own innovation strategies.

What Is Organizational Innovation?

This article defines organizational innovation as an institutional self-renewal process featuring innovative capacities. Organizations that are constantly updating have the objectives of improving organizational performance and better meeting the changing needs of clients.

Nowadays, we hear so much about social innovation, but organizational innovation may be unfamiliar. If social innovation is about the ability to empathize with people’s needs, then organizational innovation revolves around the ability to closely examine one’s own agency and be able to develop new ways to improve desired outcomes for its clients and its organizational performance.

Organizational innovation can take many forms, including organizational culture, administration and management, a new program, a new institution, new clients or a new funding model that departs from the agency’s usual course of action. Innovation varies in magnitude as well, ranging from radical to incremental, transformative to systemic.

While there is certainly a valid moral argument for nonprofits to be responsive to changing needs and to be accountable for their goals and missions, disrupting the consistent logic and culture can be intimidating to nonprofits, especially when they have been functioning satisfactorily. By definition, innovation necessitates change and unknown risk, and people by nature do not easily embrace the unknown. One might even ask, “Is it worth the effort?”

In response, Robert F. Kennedy once said, “Progress is a nice word, but change is its motivator, and change has its enemies.” Nonprofits innovate for the sake of improvement and out of necessity, but fear of change and a lack of tactics to drive innovation can be detrimental to any organization.

Acknowledging that driving organizational innovation can be challenging, this article highlights a local human service nonprofit that exemplifies how organizational innovation can be accomplished.

The Case of Episcopal Community Services

Episcopal Community Services, a faith-based, multi-service organization in Philadelphia, was founded 145 years ago and has been providing various social services to vulnerable individuals and families in the city ever since. ECS currently provides out-of-school time programming to elementary and middle school students, job readiness training to young adults, temporary and long-term housing to families and children and home care services to the elderly, among other offerings.

Major organizational changes have shifted the agency to become more improvement- and innovation-driven. One trigger was the arrival of a new executive director, David Griffith, in 2013. Since then, many initiatives have commenced at ECS, including introduction of the Center for Innovation and Impact, which creates entrepreneurial project teams across the agency for generating, pilot-testing and implementing improvement plans, launching new programs and events and shifting the culture to embrace data-driven evaluation in the human services context.

Lesson 1: A Desire to Adapt and Excel, Starting With Leadership

Innovation consists of making changes that can forge more effective outcomes and efficient operations. It is tempting, however, for nonprofits to become complacent with what may seem an acceptable status quo, such as government contracts and grant funding, and fail to reflect on whether what they have been doing still aligns with client needs, given the tides of societal change. As Voltaire put it, “Good is the enemy of great.” As society—and thus clients’ challenges and needs— changes, nonprofits that simply inherit their pasts rather than adapting to these changes will be unable to achieve excellence.

Nonetheless, change is often prompted by external factors and crises that overcome organizational inertia and resistance to change. For instance, the global financial crisis led to widespread organizational restructuring in nonprofits, governments and corporations. While external motivation and pressing economic needs can be powerful drivers for innovation and change, they are not the main factors that will sustain it. There must be an intrinsic desire for an organization to adapt and excel in order for it to fulfill its mission in an ever-changing environment, and this desire for excellence has to start with leadership.

For a nonprofit that has served its community for over a century, departure from “the norm” seemed to be unnecessary for ECS, but David Griffith instigated a desire and vision for change anyway. Coming from the for-profit sector, Griffith had the vision of creating a human service organization that would continuously improve in order to achieve its bold mission. “Given the unprecedented sea change underway, we must look to create an agency that honors its traditions while at the same time evolving into a nimble, creative organization that is world-class,” said Griffith. It is essential for a leader to know that “[i]t’s not enough to say you’re the best. You have to be the best and prove it.”

With a leadership mandate and vision for excellence, ECS is transforming its administrative processes to achieve these goals, basing improvements on evidence and evaluating the results by collecting and analyzing consistent data. Griffith’s resolve led to a vigorous self-examination, stating “Everything is up for review except our focus on our mission, our clients and our values.” Griffith envisioned ECS as becoming “an integrated agency that can quickly and effectively propose solutions to challenges and implement program and agency changes. Using the information learned, ECS can improve as an agency, impact our clients and the broader community.”

Achieving the Mission Strategically

Such an ambitious review might sound intimidating at first, but it refined ECS’s strategic mission, paving the way for embarking on innovation. ECS’s organizational mission is to “empower vulnerable individuals and families by providing high-quality social and educational services that affirm human dignity and promote social justice.” With this core mission as the guiding principle, Mary Alice Duff, chief of staff at ECS, was tasked with creating a logic model for every program and project, and with constantly reviewing them with zero-based budgets and analyzing returns on investment. This process ensures that ECS’s programs align with its core mission to serve the region’s most vulnerable.

A seminal moment subsequently occurred when Griffith, Duff and other staff critically reflected on the work of ECS. While retaining the same mission statement, the team identified the systemic root to so many of the social problems ECS works to combat—poverty. Through uncovering a service gap, they devised a new strategy to serve those in need. ECS needed to give individuals the essential tools required to lift themselves out of poverty while ensuring their security and stability through supportive services, housing and a new phase—employment.

In early 2014, a new job-readiness program for young adults was launched as a result of ECS’s desire to excel in light of the strategic review of its mission and operation. The program is called the R.I.S.E. (Resources. Independence. Success. Employment.) Initiative, which promotes the development of resources and skills that support employment obtainment, career development and self-sustainability. Participants aged eighteen to twenty-five receive one-on-one career counseling as they move through the steps necessary to gain employment such as creating resumes, submitting job applications, interviewing and networking. While working internally with participants, ECS staff externally develop relationships with employers and reverse-engineer programming, resulting in youth whose skills and experiences are tailor-made for employers. Leaders of other faith-based, multi-service nonprofits regard R.I.S.E as a very innovative program that empowers clients to be independent.

Lesson 2: Being a Beneficiary-Centered Agency: Bridging the Feedback Loop

Having a vision for excellence and being conscious of the need to adapt are necessary factors but insufficient to engender nonprofit innovation. Enabling organizational innovation in a nonprofit setting requires putting beneficiaries at the center of the agency and implementing innovation strategies based on their feedback. Without doubt, clients are the basis of many nonprofits’ missions, everyday operations and development work. When beneficiaries’ feedback is accounted for, nonprofits are less likely to coast on their efforts and more likely to focus on what they are accountable for: their impacts and outcomes. With beneficiary feedback, nonprofits possess the facts necessary to respond to their changing needs, and programs become as helpful as they are intended to be. To this end, nonprofits need to be both doers and receivers.

As much as we want to hear from beneficiaries, gathering their feedback is no easy task in the traditional donor-nonprofit-beneficiary setting. Nonprofits are caught between the donors who pay for services and the beneficiaries who receive them, as opposed to the for-profit business context in which the customers who receive the goods and services are also the payers. Beneficiaries’ responses are not directly reflected in nonprofits’ resource loops and often go unnoticed. Unless donations and funds correspond to beneficiary feedback, nonprofits are essentially the servants of two masters: donors’ wishes and beneficiaries’ needs.

To close the feedback loop, nonprofits need to not only change and purposefully solicit beneficiary feedback but also constantly evaluate and adjust their own performance accordingly. Because nonprofit innovation does not happen in a vacuum, bridging the information gap is a fundamental mandate in order for nonprofits to be accountable to their beneficiaries.

As we’ve stated, beneficiary feedback plays a major role in innovating programs at nonprofits. While companies conduct market research to obtain better sales results and ultimately maximize profits, nonprofits solicit beneficiary feedback with performance improvement in mind in order to generate better programs and achieve greater social outcomes.

At ECS, new programs and initiatives have been created while old programs have been transformed, eliminated or restructured based on solicited feedback. Like many other service nonprofits, ECS serves the most vulnerable in communities, including those who are experiencing poverty and homelessness; some also have mental or behavioral health issues. In order to better understand beneficiary perspectives, ECS formally collects feedback by sending out questionnaires to their clients and conducting focus groups for all of their programs at least twice a year. In addition, staff are able to solicit beneficiary feedback informally by developing and maintaining personal relationships with their clients. When staff cannot engage with beneficiaries face to face, they call clients to check in and attend to their requests, such as for senior care.

At ECS St. Barnabas Mission, a homeless shelter for women and children located at 60th and Girard in West Philadelphia, ECS solicits client feedback four times a year. Social workers and healthcare professionals prepare incident reports to record both daily and atypical incidents at St. Barnabas. The clients’ feedback and incident reports showed that ECS staff did not handle clients who had mental or behavioral issues and trauma particularly well. A project team was set up in February 2009, and in May 2009, a mental health survey was distributed to staff. Thirty-six responses were collected, primarily from staff at St. Barnabas. Mirroring the clients’ feedback, sixty-one% of staff reported that they were dissatisfied or extremely dissatisfied with the agency’s support when working with individuals and families with mental health issues. Staff had a basic understanding of mental health, but ECS lacked a formal training program that specifically addressed mental health and the related issues of trauma and stigma.

Years passed, and no solution to this challenge was ever implemented. In spring 2014, a project team was assembled to address the issue. Again, staff were surveyed to understand their mental health knowledge as well as to identify any underlying stigmas or attitudes that they might have had toward mental health consumers. The surveys again revealed a need for in-depth training in the areas of mental health first aid, mental health stigma, stereotyping and crisis prevention. Because both the beneficiaries and the staff reported a need for continuous mental health training, in 2014 ECS organized its first official training in order to improve the staff’s competence to manage clients with mental or behavioral health issues. It was a transformative innovation at ECS; mental health had never before been a core competency, but now all 150 staff members, including part-time staff, are better equipped to serve clients from a wide array of backgrounds.

As this example shows, beneficiary feedback provides fresh insights into the work of nonprofits. Combining beneficiaries’ input with feedback from other stakeholders such as frontline and management staff, nonprofits can quickly identify room for improvement and readily reinvent themselves through informed evidence.

Lesson 3: Cultivating an Open, Innovative Culture throughout the Agency

Trust Building and Facilitative Leadership

When Griffith took on the role of executive director, he spent the first three months talking with people and getting to know his colleagues at ECS to build trust with them. He worked alongside the previous executive director for two months and engaged with staff at different levels. This socialization process enabled the new leader to be informed about ECS’s people and issues, helping him to build strategies for the agency and positioning him as a leader who listened to, empathized with and responded to staff needs.

Aside from being a leader who strategizes and makes decisions, Griffith plays a facilitator role, enabling staff to voice anything that is on their minds. Roundtable discussions are organized every month where all staff members can openly discuss issues and concerns that are pertinent to their work and to the agency. As Griffith says, “Sometimes, as a service agency, a leader should lead by example, for instance be the first one in and last one out, cleaning up the dishes. One can’t take oneself too seriously; being a servant leader who serves with faith-based principles has made work much easier.”

Hiring and Retaining the Best Talent

Talent and commitment need to go hand in hand in the nonprofit sector. Even though compassion motivates people to work in the social services, compassion alone does not suffice to produce good work or outcomes. It is because of the complex and challenging work that nonprofits require talented people who are committed to driving positive changes. Mary Alice Duff relates the golden management principle that ECS upholds: “Talent is absolutely everything. Hire someone who is so smart that they scare you a bit…someone that can take your job. You want the best and want people who can do the job well, because the work is hard.” This statement highlights that talent is fundamental to nonprofits’ success.

Talent management is crucial to building not only a robust organization but also a new, innovative organizational culture. Griffith believes that every business is built around talent. “At ECS, talent is everything for the organization to be nimble and excellent in achieving its mission. ECS organizes itself with the best possible people to deliver the most productive work. Hiring and promoting good people and creating a great place to work, raising minimum wages for staff are the right things to do.” The question of how to reward and nurture staff resources is worth nonprofit leaders’ consideration.

It is essential for incumbent and new staff to buy in to any new innovation-driven approach. A staff member who has worked at ECS continuously for nineteen years said, “I am motivated to work here when seeing ECS becoming more and more innovative to change and adapt to our client needs!”

Through hiring new talent and promoting existing staff, ECS boosted its capacity to do good, well. “New talent can bring totally different perspectives and open up new ideas and perspectives for change and innovation,” says Duff. Kali Strother, business and performance analyst, was recruited in 2014. Strother is adept at using data to analyze and report on ECS’s program effectiveness and service gaps. In collaboration with other service providers, she leads a new initiative called the Open Outcome Project, which engages other nonprofits in the community to share their best practices and experiences with using a variety of performance management software programs. Joining in fall 2014, Cadence Bowden, an intern at ECS and a second-year dual MSW/MPH candidate, observed that there was a lack of services for adult males at ECS and in the city of Philadelphia, and she conducted field and academic research to discover opportunities to better serve the male population. These talented new staff members are among the drivers of the new culture of innovation at ECS.

Boosting Innovation Intelligence

Apart from hiring talent, ECS enables its staff to become innovative by providing room for experimentation and allowing for failure; fear of failure is often the major reason that people resist change and innovation. In creating an innovative culture, Griffith serves as a champion for endorsing new projects. “What I want to do is to train people who are closest to the work and know best about their work; train people to be comfortable taking action without a lot of bureaucracy—that’s how you build a nimble organization.”

Griffith is a big fan of “kicking the tires.” As the leader, he encourages staff to try out new strategies and pilot initiatives. “There can’t be a massive penalty if people make a mistake. If new ideas do not work, it’s okay to learn from failure.” Sometimes, a project is not perfect yet, but Griffith will still want staff to weigh in, provide input and participate in the explorative process. Through this learning-by-doing process, staff members are able to engage with and adapt the new data, and to design innovative initiatives that are informed by evidence, similar to calling an audible in football. “Based on new data, we are going to run a different play! Being a smart organization requires that it engages with staff that are willing to make an informed change based on real data and facts. Without knowing real-time responses, a rigid plan cannot get a nonprofit very far.”

Bottom-up Engagement, not just Consensus

Research found that innovation comes not from a hierarchal, top-down organizational structure but from flat, bottom-up organizations. ECS organizes roundtable open discussions with its employees twice a year, with no preset agenda, allowing staff to engage in critical deliberation and co-envisioning. ECS also maintains an open-door policy; everyone can come and talk about anything with the executive director and the management team. One tactic Griffith uses to engage is to be open and listen, trying to solicit staff input rather than just make the decisions; a common question is, “What’s your idea?” Staff at ECS are very passionate and outspoken, and they often debate vigorously on many issues. But Griffith cherishes disagreement and engagement more than consensus: “We don’t have to agree, but we can challenge each other. We are dead if we all agree! Consensus is not always the best way to get an answer; sometimes you are right and I am wrong.”

Lesson 4: Institutionalizing Data-driven Innovation: Creating an Institutional Vehicle for Innovation and Improvement

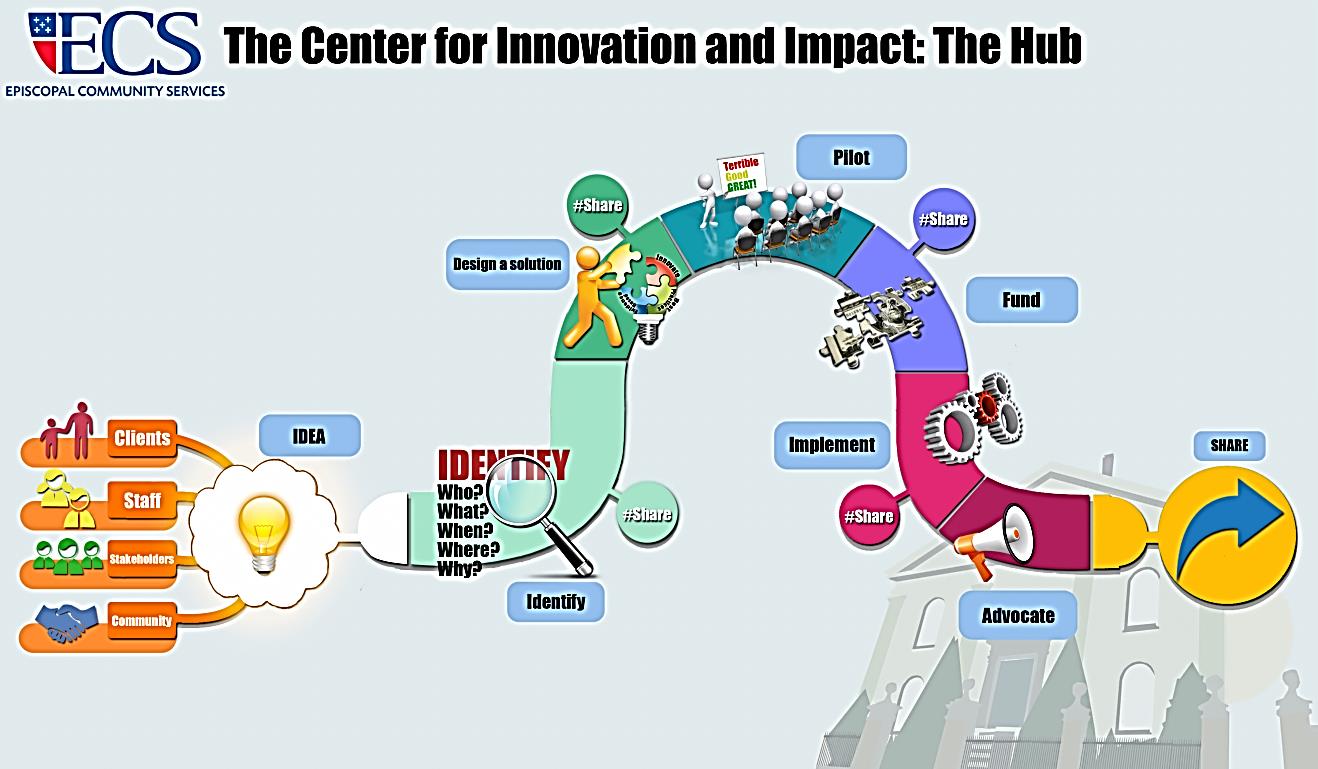

Transforming an agency requires installing an institutional structure that constantly nurtures and facilitates innovation—after all, any staff member, including the leader, could leave the organization one day. ECS has established the Center for Innovation and Impact, nicknamed “The Hub,” which solicits data to drive measurable, fact-based change based on the agency’s long- and short-term organizational and programmatic goals. Below is a chart that illustrates how The Hub works.

Led by chief of staff Mary Alice Duff and facilitated by Kali Strother, business and performance analyst, The Hub gathers facts and data to help staff propose and implement new ideas with the hope of driving thoughtful, effective innovation. It draws feedback from clients, staff, stakeholders and the community to identify areas of improvement, design solutions, run pilot tests and enact change with resources.

The Hub empowers staff to function as entrepreneurs by providing funding for pilot projects. Successful innovation involves all agency departments at every step of the implementation process, and program development takes into account the priorities of potential funders through consultation with ECS’s advancement department.

The Hub as an institutional vehicle serves as a change agent for implementing managerial and administrative changes throughout the agency. Meanwhile, it is also a platform that connects departments and program teams vertically and horizontally, involving all agency departments in the innovation process at every step. This kind of teamwork ensures that each project is sustainable, scalable and supported at every level of the organization.

Leveraging The Hub as an institutional vehicle, ECS fosters successful organizational innovation by understanding that change does not come in a fragmented or top-down manner but engagingly and holistically—the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Innovation: Realizing Performance Management and Excellence

Going back to ECS’s vision for achieving excellence, The Hub realizes this vision by employing two strategies, performance management at the program level and performance excellence at the agency level, in order to drive fact-based changes throughout ECS. Simply put, performance management is a systematic approach to collecting data on a program’s activities then using those data to make necessary course corrections or maintain gains. ECS uses monthly dashboards to review data in a timely manner to make sure that programs are on track to meet their yearly goals. Performance excellence, for ECS, is the desire to never stop improving. They use the data collected through their performance measurement system, Social Solutions’ Efforts to Outcomes (ETO®), together with their performance management strategies to inform where they need to make improvements across the agency.

Accelerate Innovation by Deploying Intrapreneurial Project Teams

Duff and other staff act as project leaders and commit 10 to 15 hours every week to lead new projects. Project teams are assembled from across the organization to address a given issue. Ten staff members across the agency collaborate on The Hub Advisory Council, and they nominate potential project team members. Once nominated, the council chairperson will ask a department supervisor if he or she is available to join the new project team. That team works for 6 to 12 months (50–100 hours) to identify or design a solution to the presented problem and implement changes. The agency’s mental health training is one example of an organizational innovation that originated from a project team.

Using Data Wisely to Inform Performance and Drive Innovation

Organizational innovation does not happen overnight; it requires thoughtful and planned effort to implement gradual systemic change throughout an agency. ECS makes use of logic models to design and implement its programs. The agency also transitioned from assessing their results on a quarterly basis to doing so in real time using ETO®; formal reviews take place monthly using dashboards. ETO® allows ECS to collect and track program activities and participant interactions, analyzing over 100 data points each month. Mary Alice Duff stated: “Taking it a step further, ECS does not just measure its performance; it also seeks to improve its performance—that’s where performance excellence comes in. It is learning how to do our work better and never accepting good enough.”

Real-time data enable ECS to make decisions on how resources are allocated, have data readily available to provide to funders and stakeholders, better communicate their outcomes-based results to potential funders and assess their impact on the community.

Conclusion

At ECS, organizational innovation is not a whimsical notion—it is coordinated, beneficiary-focused and evidence-based. It is also a collective learning process for leaders and staff to realize the impact that they make and the gaps that they miss.

The time is right to look past nonprofits as traditional, old-fashioned agencies that maintain programs: they are, rather, institutional change-makers that can be innovative and regenerative when they incorporate beneficiaries’ feedback, garner the support of their leadership, instill open learning cultures that encourage new ideas and establish institutional structures that facilitate evidence-based innovation. Innovating nonprofits, such as ECS, are pioneers that reconsider the approaches with which they serve their clients, mobilize talent and assets and make use of stakeholder feedback and data to create innovative initiatives.