The economic recession rekindled the acrimonious debate about the role of government in funding social programs like housing and community development. For those of us on the ground in poor communities, public funding is a lifeline. By definition, poverty is the lack of money to address basic needs.

We have seen over and over that neighborhoods can be rebuilt. With the right mix of strategies, they can attract private investment and grow. But government almost always provides the venture capital for poor communities.

Similarly, individuals experiencing poverty simply lack the income to meet their basic needs, let alone save or build wealth. Housing subsidies can make the difference between a precarious, despairing living situation and the stability to succeed in school or career.

But how can we win legislative support for affordable housing in such a hostile environment?

The successful campaign to establish and fund the State’s Housing Trust Fund offers insight into an innovative and replicable approach for winning support for a social program.

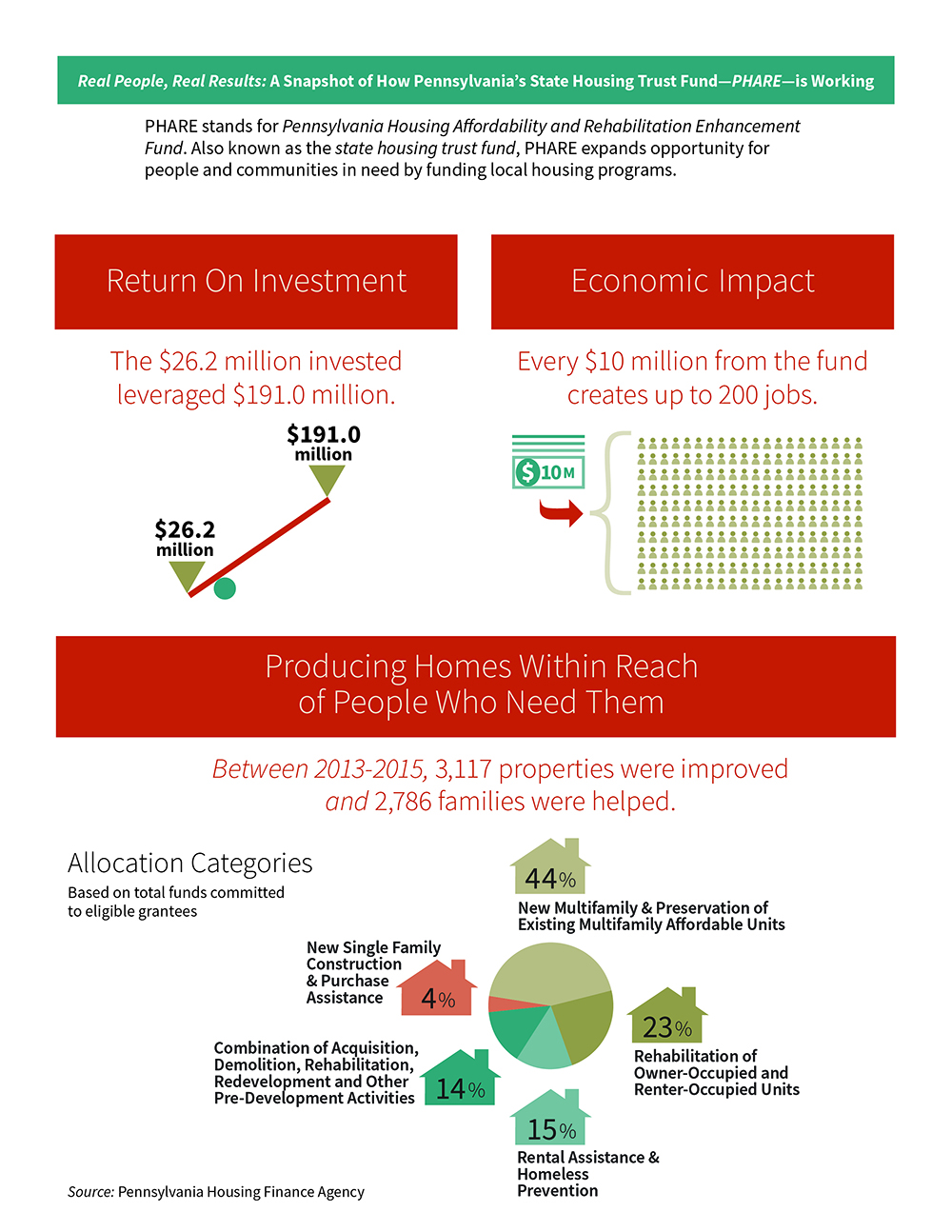

On November 5, 2015, Governor Wolf signed into law a bill that establishes a $25 million annual revenue source for the Pennsylvania Housing Affordability and Rehabilitation Enhancement Act (PHARE). The money provides rent subsidies, home repair and rehab, development, homeless assistance and homeownership support, all of which are traditional affordable housing solutions, for people living on low and moderate incomes.

The passage of an affordable housing funding bill with a near unanimous legislative vote (242-1) in the midst of the longest and most bitter budget feud in Pennsylvania’s history provides strategies that are surprisingly replicable. This article deconstructs and lifts up lessons learned from this remarkable campaign.

Our Story

The Housing Alliance of Pennsylvania is a statewide coalition of housing, homeless and community development practitioners, both for-profit and nonprofit. As early as 2007, Alliance members reported lack of funding as the single biggest obstacle that they faced. That situation escalated with the housing market crash. Homelessness grew, demand for apartments and rents sky-rocketed, public and philanthropic funding went down.

The Housing Alliance set winning a State Housing Trust Fund as the top priority in our 2008 strategic plan.

A Trust Fund is the holy grail of housing funding. From a programmatic perspective, it is a dedicated revenue source limited to needs-based housing, yet it’s flexible enough to respond to diverse and changing local conditions. It ensures opportunity for community input through a mandated annual public planning process.

From a campaign perspective, the battle, once won, does not have to be refought through the annual appropriations process. Elected officials appoint the board of the administering body, giving them a say in the use of the money. A “rainmaking” strategy, there are a wide range of beneficiaries with a stake in the outcome of the campaign.

Rather than embracing the conventional wisdom of a multipronged agenda, we focused instead on a narrow agenda embraced by a broad, at times strange-bedfellows’ coalition. The 175 endorsing organizations included everyone from religious leaders to politically-connected developers to grassroots homeless and human services providers to local and county governments.

The Housing Alliance broke with tradition and created a partnership with the administering state agency, the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency (PHFA). Conventional wisdom for advocates suggests the administering agency is the target of organizing actions. Yet PHFA had a stake in establishing the Fund; they were being deluged by demand while managing a shrinking resource pool.

Our game plan was an insider-outsider approach. PHFA has access to official channels, a data and funding infrastructure and a legislatively established board.

The Alliance, in contrast, has a broad-based, statewide membership. We connect elected officials to voters in the district, where it counts. Our members meet with legislators in their own back yards to connect the dots between local need and the promise of the statewide fund.

For the campaign, the Alliance organized and deployed an aggressive strategy. If lack of housing is really an urgent problem, then we had to convey urgency. We asked for legislative hearings and briefings to keep the issue front and center. We published reports, held media events, placed opinion pieces and organized legislative visits.

Our message never veered from the positive. We were sometimes counseled to attack and condemn as a political strategy. We did not. Our membership wanted a positive, solutions-based campaign, even if that meant slower progress.

The early efforts paid off in December 2010, when the bill establishing the Trust Fund was signed into law by Governor Rendell. The humbling process of getting a bill to signing taught us several important lessons.

Before the bill was signed, it was amended to remove the appropriation. It became a Fund with no funds. The Housing Alliance was faced with a dilemma. Do we kill our own bill because it falls so far short of what we need? Or do we take it as a victory and try to convince our disappointed coalition members that an empty bill is a step forward? We decided to embrace the bitter victory as progress and continue the fight. Why? Because progress equals success. Success makes you a winner. And, most importantly, now we had a Fund.

As a result of this agonizing choice, the Housing Alliance’s power and influence actually grew.

This is how we decided to embrace incrementalism. A legislative staffer once told me that advocates love big packages, but legislators like small steps. Lawmakers actually respect the magnitude of their responsibility. They try to pass laws carefully. That sometimes means taking one safe step at a time.

We turned incremental progress to our advantage. In February 2012, we got that empty Fund funded with Marcellus Shale Impact Fees under Governor Corbett. The Fund now reached half the counties. We embraced it as a pilot program to prove that a trust fund could work. Today, the program has invested $34 million helping 4,000+ households and leveraging nearly a quarter of a billion dollars.

The pilot program also provided data, which was critical. Thanks to the careful structure and administration, success became the selling point for expansion. The program had been tested. Legislators could safely support it. We could build on success.

Even with the seeds of success planted, moving a revenue bill requires the right sponsors. They must be majority party, able and willing to navigate a pathway forward. The bill sponsors, especially in the notoriously contentious House, needed the support and respect of their peers and leadership.

Bipartisanship became the biggest lesson. Quite simply, it is impossible to get anything done in either state or federal capitols without support from both political parties. We had to find common ground, to find a way to talk with people we didn’t know very well. We landed on “shared values.”

We discovered that people can agree on core values. If you work hard and play by the rules, you ought to be able to afford a decent place to live. No child should be homeless. Seniors and people with disabilities should be able to live safely and with dignity.

The “disconnect” between these shared values and the reality faced by so many created a platform for talking about solutions. We had a solution: the State Housing Trust Fund. It just needed funding. For that, it needed legislative champions from both parties.

Working side-by-side with Republicans and Democrats has been the most challenging and rewarding aspect of this work, the most important and the hardest. Think for a moment about your own stereotypes about the “other” political party. We have been indoctrinated into an adversarial way of thinking about political party by people who benefit from divisiveness. We challenged the status quo by working with both parties, taking their counsel and allowing ourselves to be educated about differing points of view. At the end, we found out just how challenging it is to be bipartisan when our bill was threatened with a veto after winning near unanimous support.

Bipartisanship, it turns out, is the new radical.

A revenue source was the final puzzle piece. Quite simply, to win in today’s climate, we needed a revenue-neutral source. At the same time, we couldn’t take money away from another program and incite a distracting and potentially unwinnable turf war.

We hit on the idea of future growth in Realty Transfer Tax (RTT) proceeds. Intuitively connected, RTT money would go from housing to housing. It made sense, except for one small problem: the powerful 40,000-member Pennsylvania Association of Realtors® had “concerns.”

The strange bedfellows’ coalition worked. Realtors were already our partners in that they care about housing for all. Working closely with their leadership, they revisited their opposition. The final barrier was down.

A dedicated annual Housing Trust Fund revenue source became law. Through the work of a diverse, patient coalition unified around a positive, proven solution, legislators and community, rural and urban, “D’s” and “R’s” came together to improve the lives of vulnerable people and their communities. There are lessons in this experience for all.

Liz Hersh is executive director of the Housing Alliance of Pennsylvania, and will transition to being director of the City of Philadelphia’s Office of Supportive Housing in March 2016.