Summary

The high mortality of mothers and babies in low-resource settings in developing countries is well-known. Attempts to change this continue, with both successes and failures globally. Even when success is achieved, sustainability is a problem. The problem of high maternal and neonatal mortality was seen in remote villages of the hilly, forestry region of a district in central India. This region is known for its wildlife and the difficult five to six-hour drive from the referral institute. As a step towards social responsiveness, a beginning attempt was made from a medical institute with help of the team of health providers with infrastructure. Consultants, residents, and interns are posted in rotation, and are provided free accommodations, television, four meals a day at no cost, a mini library, and access to indoor and outdoor recreation. As hospital-based services were started it was realized that creating a health facility was not enough, and that it was essential to provide community-based services so that nurses who were hired, could retrain others to provide basic antenatal care and advocacy for neonatal and postnatal care. In the beginning delivery kits were provided in the villages to the families as the number of home births was higher. Kits were donated by an overseas civil society organization and now donations have stopped, and home deliveries have been reduced.

Advocacy is also being done for birth preparedness and complications readiness. Preconception care has been added in the recent past. Each pregnancy is being followed and community-based maternal morality ratio has been reduced to 162 from 400 previously. Childcare has been added now and many lessons have been learned.

Background

High mortality rates of mothers and babies in low-resource settings in developing countries is well-known. Attempts to change this scenario continue, with both successes and failures globally. Even when success is achieved, sustainability is a problem. The problem becomes magnified in regions where there are access problems and lack of awareness, resources, infrastructure, and extreme poverty. There are issues of culture and beliefs that impact this too. So, providing and seeking maternal child healthcare becomes difficult. Therefore, the health of mothers and babies suffers.

Problem Identified

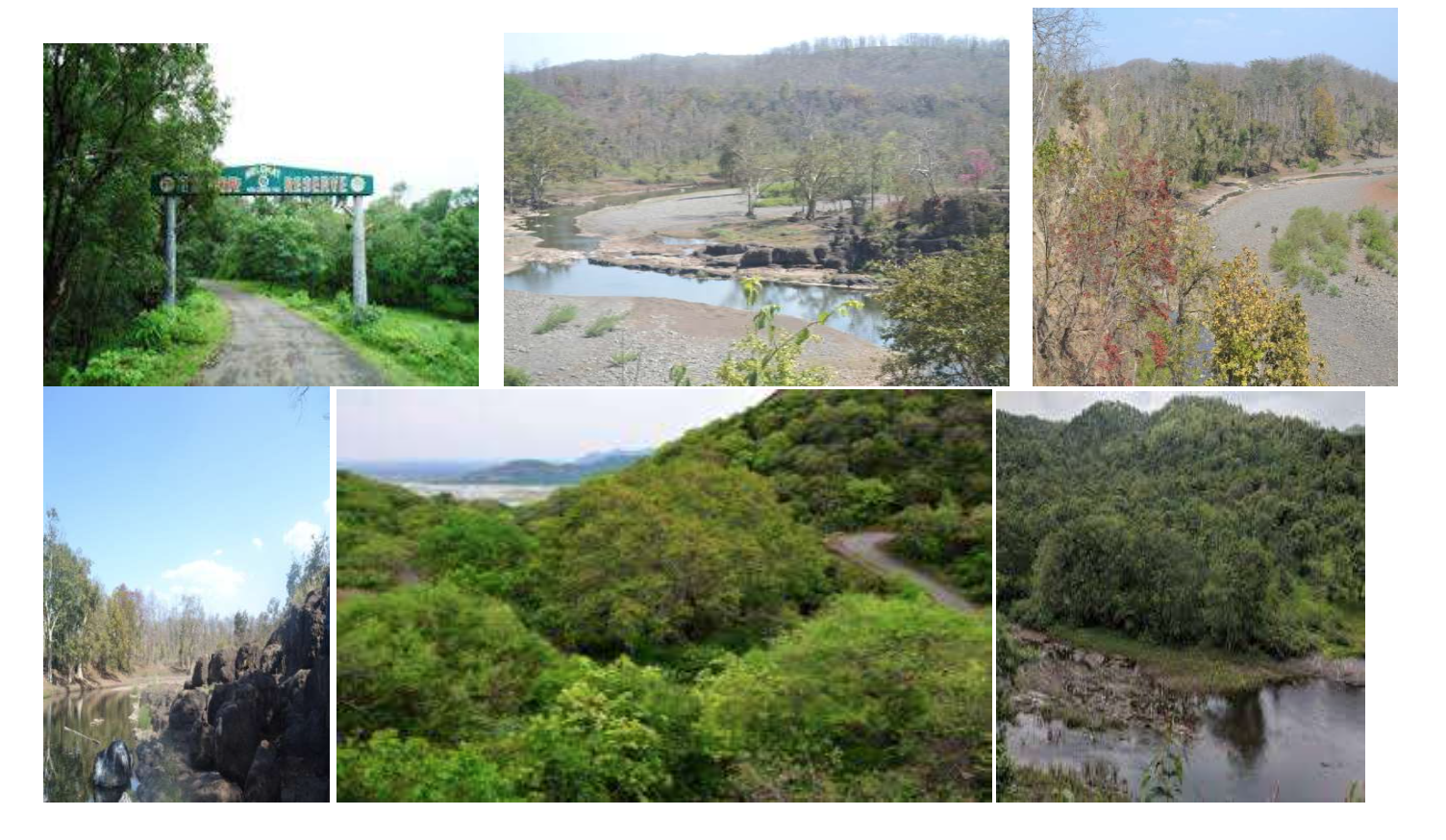

The problem of high maternal and neonatal mortality was seen in the remote villages of the hilly, forestry region of a district in central India of a province which was otherwise doing well. The region is known for its wildlife, beautiful but tricky terrain that is a difficult five to six-hour drive from the referral medical institute in the nearby district.

Melghat Region

Methodology

As a step towards social responsiveness, a beginning attempt was made by the medical institute to help the rural tribal women of these communities who were living in extreme poverty. It was decided that it was necessary to have a team of health providers and the infrastructure. However, all of the attempts to get health care teams to provide rural health care were in vain. It was essential to have needed infrastructure, to begin to offer services for the mothers and babies. Governments were approached to request needed resources, state as well as center. However, politics and bureaucracy were big hurdles so civil society was approached for help in regard to the needed infrastructure. It began with the expansion of 25-beds hospital to 50 beds that currently has accommodation for 150 in future, all without interrupting the ongoing work of the hospital. Watchmen and technicians were available from nearby townships and villages and in the beginning; nurses also had to be deputed. Later nurses of nearby places trained at main referral institutes and other places were able to join. Medical officers, (basic doctors who were trained at the base institute) also joined under the Institute’s post-graduation rural service rule which required two years of rural service as a prerequisite for application to post graduation at the institute. However, one year was needed prior to application, and the second year offered the option of doing rural service after graduation. The institution identified around 100 non- government organizations which had hospitals with in-patient services in the villages, for doctors to select and join, and some joined Melghat too. However, the Government’s changed rules for PG selection affected this well-planned system of providing rural health care by doctors stationed in the village. A plan for sustainable health care for remote rural populations was coming to a standstill. Yet, attempts to service this population continued. In the beginning, two interns were posted for two weeks so that they became a team of service providers and learned about rural health care. They were deputed from the medical institute. When MO were not available, the number of interns was increased, overcoming resistance from some at the institution, around four to five deputed to two weeks in rotation. All repeated attempts to get even basic doctors in the remote region failed. Consultants and residents (postgraduate students) were posted in rotation for six weeks at a time. These deputed health providers were also provided free accommodation including television, four meals per day at no cost, a mini library was made available, outdoor and indoor activities were provided., and wifi was available in a shared mini area. A system for free transportation for the exchange of teams from the base medical institute to the hospital was created in one of the villages in the nearby district. Vehicles were also provided twice a week in the evening for two hours, for teams to go to nearby townships for any personal needs because the hospital in the village is located in the forests with no shops within seven to eight kilometers. In the beginning mobiles were also provided but they were difficult to manage so that has stopped.

The hospital has been reasonably equipped for 24 hours a day, seven days a week for services for all specialties but the thrust is on mothers, rather women and childcare. Health provider teams run outpatient services six days per week, but no one is refused, even on a Sunday a c-section is available. To get help for sonography not only from the institute but from the district has failed, but finally help from nearby state has been sought for sonography twice a month.

Once hospital-based services were started it was realized that creating health facility was not enough. It was essential to provide community-based services. Rural pregnant women had no way to get to the hospital for postnatal check-ups or for care of their babies. In response, more nurse midwives were hired for community-based care and retrained in the hospital for the job they were expected to do in the rural communities. In the beginning services were started in 52 villages, later on villagers requested more services and it was extended to 65 villages. Then by looking at the needs and resources available the numbers, services have been increased to 140 villages. Attempts continue to provide basic antenatal care and advocacy for neonatal and postnatal care. In the beginning delivery kits were provided in the villages to the families as number of home births was higher. Kits were donated by an overseas civil society organization. Now donations have stopped, and home deliveries have been reduced.

Advocacy is also being done for birth preparedness and complications readiness. Preconception care has been added in the recent past. Each pregnancy is being followed irrespective of the place and mode of outcome. Community-based maternal morality ratio has decreased to 162 from 400 previously. Malnutrition in infants and children continues to be a problem. Mothers are unable to do exclusive breastfeeding for newborns as they have to earn a livelihood, they also lack awareness, so infant health also suffers. As babies grow, mothers are unable to provide the needed food for their children, so their health continues to suffer. Now advocacy is also trying to find ways of improving breastfeeding to ensure it is accessible and sustainable. Many families do have jiggery, oil, ground nut, gram, and goat milk. Advocates are now asking for them to give whatever is available to the families, in hopes of improving safety as the baby ages. Some organizations might help in fortified foods, but it still is not encouraged for safety and sustainability.

However, attempts continue to involve stakeholders, government, and civil society as resources are needed to start sustainable and useful development of initiatives. Last and most importantly, villagers use local items to keep them healthy in many situations. There have been no deaths due to septic abortions. Hardly any woman used health facilities for abortion care. Also, the concept of family planning does not seem to exist. Induced abortion is sought much less often which results in larger families. Social behavioral research is needed. Our attempts to continue to learn and provide services for healthy mothers and babies continues.

Conclusion

Many lessons have been learned. These communities have their own strong beliefs about witchcraft and quacks who are seen as healers. The daily struggle for square meals does not allow families to think of the needs and care of pregnant women. Also, pregnant women seem to shy away from health facilities, which begs the question, Why!

S. Chhabra, Emeritus Professor Obstetrics Gynecology, Ex. Dean, Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences,Sevagram, Officer on Special Duty, Dr. Sushila Nayar Hospital, Utawali, Melghat, Amravati, Chief Executive Officer, Akanksha Shishugruh, Sevagram, Kasturba Health Society, Sewagram, Wardha, Maharashtra, India and Teams